Quebec developed rapidly between the 1960s and 1970s. Companies gradually became interested in the natural resources located in Northern Quebec and in more remote regions. As such, companies were moving closer to land reserved for Indigenous peoples. Indigenous communities were concerned that these companies would encroach on their territory, so they demanded recognition of their ancestral rights and land, but also self-government.

The Indian Act of 1876 made Indigenous peoples a separate class of citizens in Canada. This Act gave members of these communities special status, which granted them certain benefits such as a tax exemption for living on a reservation. To be recognized and to receive special status, a person had to prove their Indigenous ancestry and live on a reservation in order to be exempt from taxation. However, the Indian Act was originally intended to assimilate Canada’s Indigenous peoples by limiting some of their rights and ensuring status would be lost over generations.

In 1969, Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau wanted to abolish this Act. This resulted in Indigenous peoples losing some of their rights since they would no longer have special status; the government would no longer have to sign agreements with Indigenous communities living on the land in order to use its resources. Faced with this possibility, Indigenous groups came together to protest the abolition of the Act. They wanted to keep their rights and their special status. In 1971, the government changed its plan and the Indian Act was upheld.

The Indian Act provided Indigenous people with land on reserves, which they self-governed to a certain extent. However, this form of self-government was severely limited since the communities had to follow federal laws. The Indigenous nations protested this situation by demanding broader self-government. This granted Indigenous communities more power so that the federal government could no longer make decisions for them.

To make their demands heard at various levels of government, the Indigenous nations banded together. Through these organizations, the communities worked together to put pressure on governments. The National Indigenous Council was created in 1970 and the Native Alliance of Quebec was created in 1972. While the federal government did grant some rights, most communities were not granted full self-governance.

The increasing demand for raw materials attracted industrial companies to the territory. Since some of this land belonged to Indigenous communities, and governments had to sign agreements with the people living there. The government recognized some, but not all, Indigenous territories. Several communities campaigned to have them recognized as ancestral land.

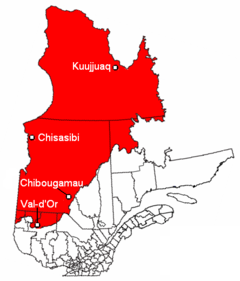

As the demand for electricity grew, Hydro-Québec wanted to build new dams and was interested in building dams on the province’s northern rivers. In 1971, it began work on the La Grande complex without signing a treaty with the local communities. The local Indigenous peoples strongly opposed this project, asserting their ancestral rights to the land.

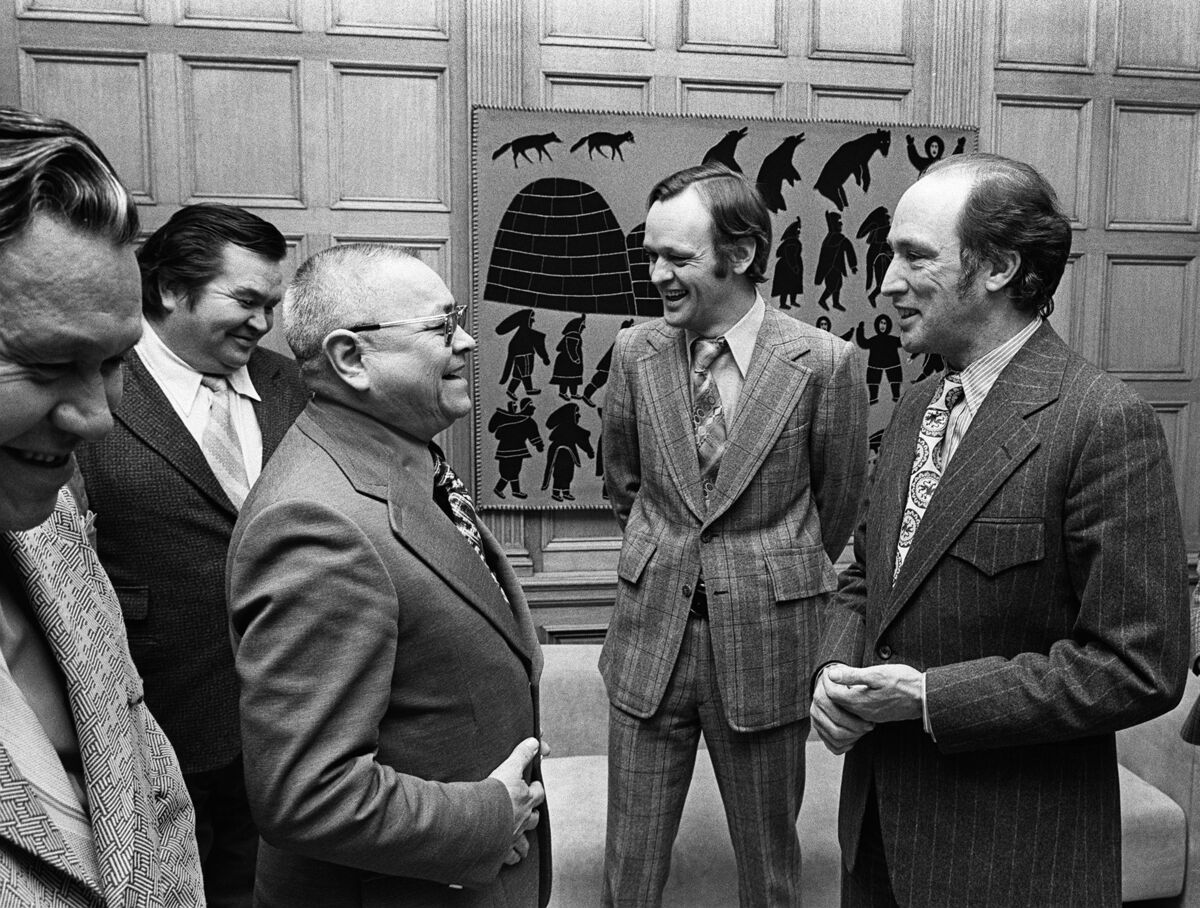

Pressure from Indigenous groups temporarily halted the project in 1973. The provincial and federal governments met with the Indigenous communities to negotiate terms regarding the land. After two years of negotiations, the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement was signed in 1975.

This agreement recognized the Cree and Inuit’s exclusive rights to the territory. This gave them hunting and fishing rights within the territory as well as greater self-governance. While they did not gain more autonomy within the territory, the communities were allowed to govern themselves at a local level. The Quebec government was allowed to exploit forestry, mining and water resources, including rivers, in exchange for financial compensation paid to Indigenous communities. This was the first time governments officially recognized Indigenous rights.

With the construction of the dam well underway, Hydro-Québec created more reservoirs and hydroelectric complexes in the territory. These new construction projects directly affected the Naskapi people living in the area. This community wanted to negotiate with the government, as the Inuit and Cree had done. In 1978, an agreement was signed between the Naskapi nation and the government. The nation received financial compensation for the use of the land and obtained exclusive hunting and fishing rights over a large part of the region.