The concepts covered in this factsheet go beyond those seen in secondary school. It is intended as a supplement for those who are curious to learn more.

Industrialization in the United States took place after the American Civil War, between 1865 and 1918. This period was marked by a sharp rise in demography, strong economic development and the conquest of American territory. None of these factors was solely responsible for American industrialization. Rather, it is the fact that these factors occurred simultaneously that explains the development of industries in the United States.

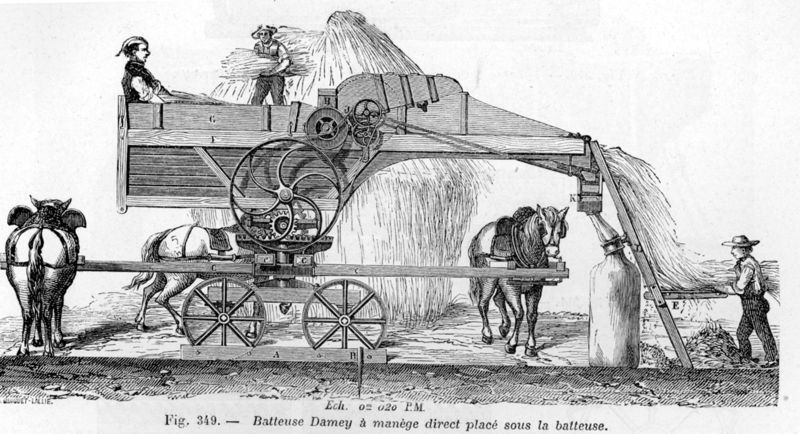

At the start of the Industrial Revolution, agriculture was the main economic activity in the United States. This period was particularly marked by the transition to mechanical farming. Between 1860 and 1910, the number of farms tripled, rising from 2 million to 6 million. What's more, these farms occupied a larger area of land. This development would not have been possible without technological innovations such as the harvesting machine. Invented in 1840, this machine made it possible to harvest a large area quickly and efficiently. The development of agricultural technologies continued with the invention of other machines and the opening, in 1861, of several technical colleges dedicated to agronomic research.

Cotton is the most important agricultural crop in the United States, and has been since 1793. In fact, it was in this same year that the machine that separates the cotton seed from the fibre was invented. This new invention speeded up the task considerably, driving down the price of cotton and making it more accessible. As a result, the United States began exporting large quantities of cotton to Europe.

Cotton growing, even when mechanised, required large numbers of workers. In the United States, this was not a problem, as there were plenty of slaves. The spinning industry developed at the same time, bringing together all the stages in the processing of cotton, from gathering to yarn. Weaving and knitting machines were also developed. So it was at this time that cotton cultivation took off in the United States.

In 1789, a British man named Samuel Slater arrived in the United States and set up a cotton mill in the town of Pawtucket, in the northern state of Rhode Island. The southern states supplied the raw materials and the northern states had the factories to process them. Even today, the United States produces 35% of the world's cotton.

The industrial development of the United States was helped by the arrival of many British immigrants. They brought with them the industrial experience of Great Britain: knowledge of machines, technologies, industries and so on. At the same time, growing military needs stimulated the creation of numerous industries and the development of science and inventions.

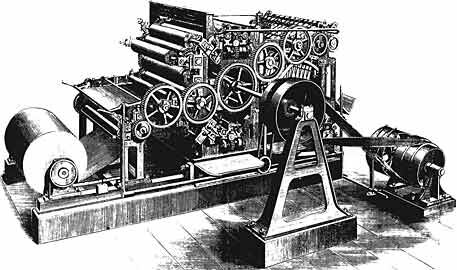

The pioneer of American industrialization was no longer the colonist or explorer: it was inventors, merchants, capitalists and philanthropists who were valued. This is why the Industrial Age was marked by numerous inventions: the electric telegraph (1844), the rotary press (1846), the typewriter (1868), the compressed-air brake (1868), the telephone (1876), the key-operated adding machine (1887) and the cash register (1888).

The inventor with the most patents is undoubtedly Thomas Edison, best remembered for his invention of the phonograph and the incandescent light bulb.

Otherwise, industries were set up in much the same way as in Europe: factories founded close to towns and raw materials, rapidly expanding cities and new rail links facilitating the transport of raw materials. Villages became towns, and towns became cities, attracting capital and financial and industrial establishments.

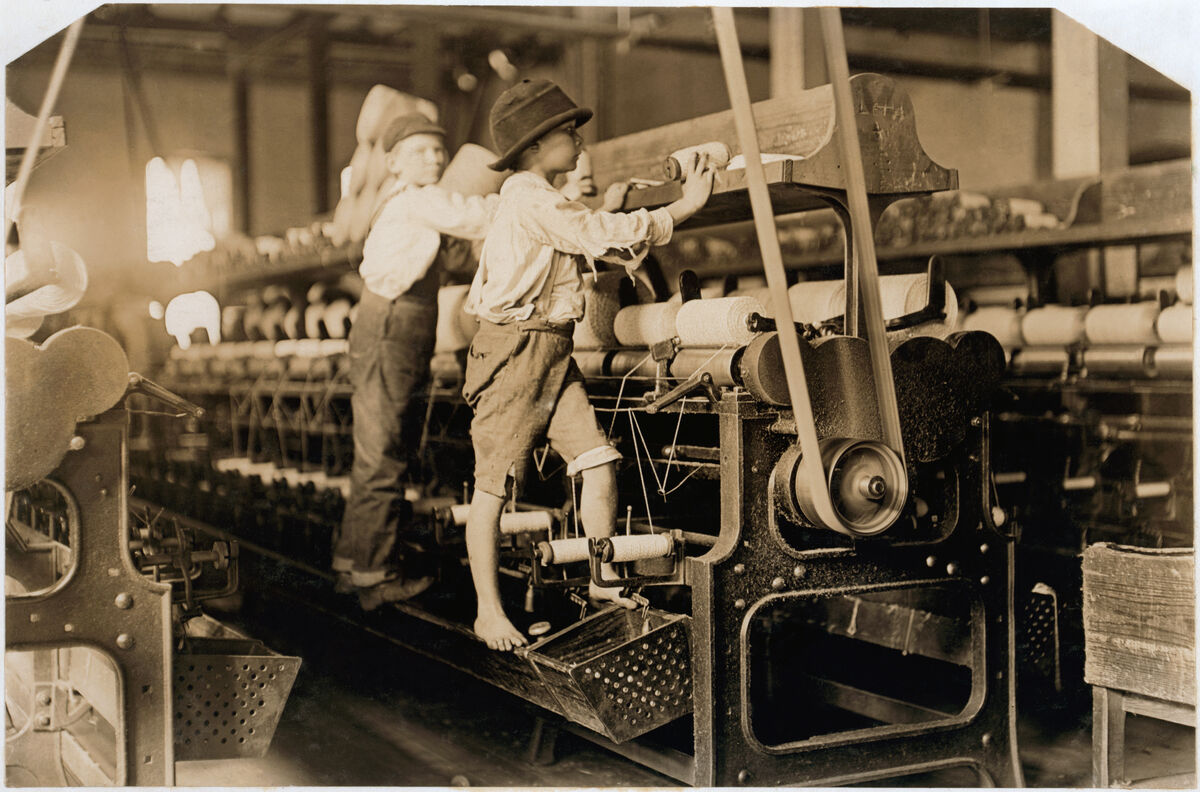

In the early days of industrialization, workers had to endure arduous working conditions similar to those in Britain. Women and children worked just as hard. However, the workers did not question the system of economic profitability. They demanded a greater share of the profits made, without being outraged by the profits generated by the company.

Many children worked in factories, mines and manufacturing plants. No laws existed to protect young people.

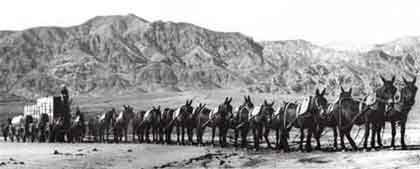

On 22 April 1889, the Homestead Act marked the beginning of the race for land. Under this Act, the leaders granted free land to all families who undertook to occupy and develop this land for at least 5 years.

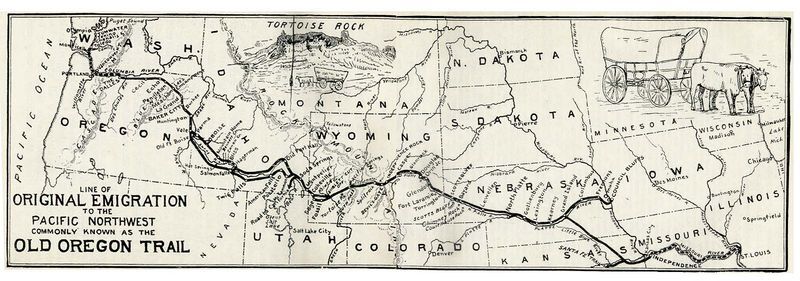

Many families took advantage of the opportunity and obtained their own land. Located further west, these new lands increased the territory covered by the American population. For the most part, they were located on former Indian lands that had been opened up for colonization in 1889. In a few short years, the whole of the American territory was covered, and civilisation of European origin covered the country: economic activities, exploitation of the soil and processing of raw materials.

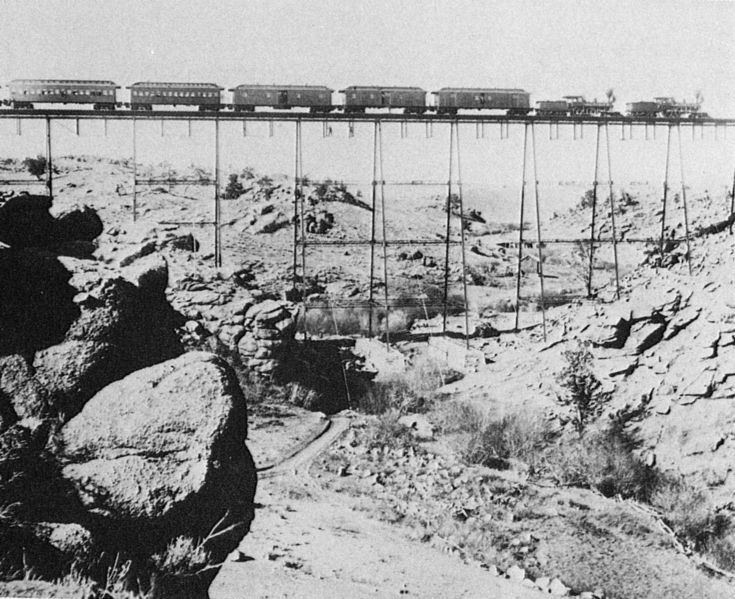

Unlike other European countries, the American territory was still being developed when the train was invented. Railway networks made a major contribution to the expansion of the territory, since trains could link towns together, reach natural resources and develop remote areas. Trains could also connect ports, making it easier to transport goods for export.

In 1869, the first transcontinental line was created between New York and San Francisco. This line made it possible to make the journey in a week, compared with 6 months before the arrival of the railway. All regions, from the Atlantic to the Pacific, were linked by rail. Expansion towards the western territories was stimulated by the discovery of numerous gold, silver and copper deposits. The network therefore had to link the settlements founded by the mining companies, the newly colonised territories and the farmlands. With the construction of the railway, livestock farming expanded with the opening of numerous slaughterhouses and meat preparation industries.

The arrival of the railways did more than just develop the country and open up the land. All the owners of the railway companies benefited from this rapid expansion. The railway companies grew larger and larger and exercised strong control over all economic activities. As industries depended on rail transport to function, the railway companies did not hesitate to be ambitious: excessive prices, large discounts, profit-sharing between rival companies, etc. In a very short space of time, the railway companies were among the most powerful in the United States.

At the dawn of the 19th century, the first shipping lines began to offer regular services: transatlantic crossings for passengers and goods. These new forms of transport were steam-powered. Boats continued to evolve with the invention of paddle steamers and iron-framed ships. All the new shipping lines created efficient links between ports. Steamships, which were faster and more efficient, stimulated the development of new ports: larger and linked to industrial complexes. These new infrastructures made extensive use of raw materials.

The oil-fired engine increased the loading capacity of ships while reducing their consumption: ships travelled faster at lower cost. As far as urban transport is concerned, electric power has made a major contribution. The invention of the electric tramway in 1870 changed the way workers and city dwellers lived. Later, it was the invention of the internal combustion engine that transformed urban transport and the face of cities, with the arrival of cars, buses and trucks. The rise of the car created new needs for petroleum products. Maritime transport adapted with the creation of new shipping lanes.

The massive spread of the car has considerably altered the structure of towns and cities, making a major contribution to the expansion of suburbs and urban sprawl. This is one of the factors behind the formation of mother countries and huge megalopolises.

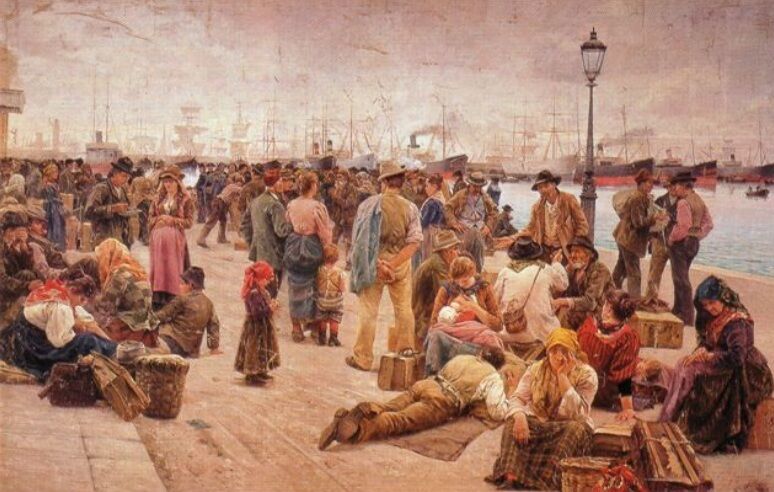

As well as helping to increase the occupation of the land, the Homestead Act succeeded in attracting large numbers of immigrants. Between 1860 and 1920, for example, the US population increased dramatically. This increase was mainly due to mass immigration and not to the birth rate.

Here is a table showing the evolution of the population in the United States:

| Date | Population |

| 1860 | 31 million inhabitants |

| 1890 | 62 million inhabitants |

| 1900 | 75 million inhabitants |

| 1920 | 105 million inhabitants |

To better accommodate all these new arrivals, the United States created a new immigrant reception centre on Ellis Island, north of Manhattan in New York. Welcoming an average of 1 million new residents a year, this station was in service until 1943.

The new waves of immigrants come from a wider range of countries than in previous years. Before the great waves of immigration, the majority of American immigrants were of British origin. From the 19th century onwards, there were immigrants of many origins: Latin, Slavic, British, Scandinavian and Germanic.

A number of Americans feared that these immigrants from different backgrounds would alter the composition of American society. Some even suggested restricting immigration. Several treaties were signed to control the origin of immigrants. The first of these was the Chinese Exclusion Act, which came into force in 1882. This treaty prohibited all immigration of Chinese origin. Only the Chinese already in the country were allowed to work and travel in the United States.

The strictest treaty relating to immigration was the Immigration Act, which came into force in 1924. This treaty set quotas limiting the percentage of new arrivals from any one country to 2% of that country's population already present in the United States in 1890. It also prohibited immigration from all Asian countries. It did, however, allow free immigration for all American countries.

Despite Americans' fears, the flood of immigrants has nonetheless had a number of benefits for the country's demographic and economic development. These waves of immigrants made it easier to increase the occupation of the land while providing the workforce needed for new industries. What's more, these new arrivals have increased the customer base for national production as a whole.

The Knights of Labour was one of the first trade unions. Founded in 1869, it brought together workers from many different trades. By 1886, the Knights of Labour had more than 700,000 members.

Immediately following the rise of American capitalism came the development of factory working methods. The aim of these methods was to organise work rationally and logically in order to save time in production. For example, it made sense to have workers who could work longer hours and produce more in the same day. At the time, rationalisation was necessary to keep up the pace of production and maintain growth in output.

In this new way of thinking about factory work, people had to adapt to the pace of the machine, not the other way round. Skilled workers were those capable of synchronising themselves with the machine.

In 1878, F.W. Taylor was a worker in a metal factory. Some time later, Taylor was promoted to foreman. It was while in this position that he began to develop his scientific organisation of work.

In his view, the problems of loitering in factories were not caused by the workers, but rather by the methods and organisation of work, which he considered to be poor. This is why Taylor developed his principles of the scientific organisation of work in 1880. His aim was to ensure that tasks were carried out in the best possible way, with a good distribution of work, good coordination and control of everyone's activities. Only reorganisation could enable industries to meet demand and produce large quantities at lower cost.

To achieve this, Taylor dictated the following principles:

- Each employee always did the same job;

-

Production was broken down into a multitude of tasks: employees only had to perform simple actions, and unnecessary actions had to be eliminated;

-

Decrease employee relations to increase profitability;

-

Introduction of individual bonuses and rewards for the most profitable employees who meet the standard;

-

The time allocated to each task is pre-established;

-

Execution of tasks and control are two actions carried out by different individuals.

Inspired by Taylor's principles, Ford took the concept of rationalisation a step further. In fact, it was this boss of the car industry who created the assembly line. In order to further reduce the amount of work required of the worker, the assembly line brings the work to the worker. As well as organising the work of each worker efficiently, the assembly line increased product standardisation, meaning that all machined products are identical. Ford's assembly line made it possible to launch a new model of car: the Ford T. The first mass-produced car, the Model T was manufactured 12 times faster than any other car.

All these new ways of organising work really increased companies' production capacity: mass production was now possible. This enormous production also stimulated new consumer needs: it was the beginning of mass consumption. On the other hand, for the workers, this organisation of work had no beneficial effects: fewer simple gestures constantly repeated, greater monotony in the work performed, increased absenteeism, demotivation at work, rise in work-related accidents, etc.

It should be remembered that Taylor and Ford never took into consideration the human and social problems associated with industrialization and their organisation of work. On the other hand, the simple, repetitive work performed by workers was the cause of many social conflicts and class struggles. A cinematic representation of this industrial era can be seen in Charlie Chaplin's film Early Modern.

During the Industrial Revolution in the United States, all industries experienced a meteoric rise. Employers invested capital and reaped the profits. At the time, there was no clear legislation on monopolies and trusts. As a result, several companies controlled all production. They could therefore manage prices and tariffs as they saw fit, since there was no real competition. This was the case for the mining, rail and oil industries. Taking advantage of the situation and the opportunity to build very rich commercial and industrial empires, American entrepreneurs amassed enormous fortunes.

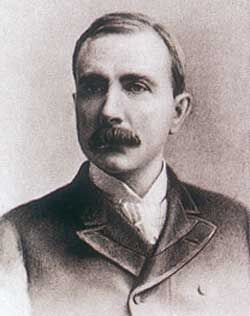

The best known of these wealthy capitalists is undoubtedly John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937). One of the first great American capitalists, Rockefeller built an economic powerhouse in the United States. All his life, he applied one of his mother's teachings: in life, you have to work, save and give back to the poor.

However, Rockefeller realised quite early in life that investing his money wisely was much more rewarding than working. In his view, it was absurd to work for money when money could work for him. That's why Rockefeller went into business, quickly learning its principles, before going out on his own and starting to reap substantial profits.

Rockefeller amassed his wealth mainly through his oil refining company. His company soon dominated the market. Some rival companies had been bought out and the company took advantage of the railways' low rates. Profits rose steadily while competition fell. The Standard Oil Company controlled the entire oil industry: refining, distribution and the manufacture of by-products, and had bought out all its competitors. By 1879, the Standard Oil Company was refining 90% of American oil and was the world's only producer of paraffin. Despite government attempts to enforce anti-trust laws, the Rockefeller-led monopoly was making huge profits.

Rockefeller nevertheless left the company before it was dismantled, even though he was a billionaire. He then began a new career devoted to philanthropic activities and charitable causes. Among other things, he founded :

-

The University of Chicago, in 1890;

-

A medical institute in New York, to study the causes and prevention of disease, in 1901;

-

An educational institution, to which he donated a great deal of money over several years, in 1902;

-

A health commission, in 1909;

-

The Rockefeller Foundation, to promote the welfare of humanity throughout the world, in 1913.