In Mesopotamia, a city-state is a town that is the capital of a kingdom and has its own government and institutions. It is completely sovereign.

Mesopotamia was home to a number of cities known as city-states, i.e. cities with the same powers as a modern-day country. It was able to make all its decisions independently of other territories. In other words, a city-state has its own government, its own laws and its own institutions. However, the form of governance can vary greatly from one city to another.

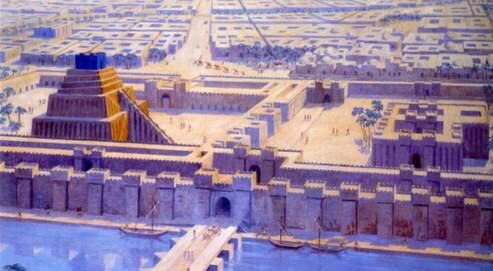

Although Mesopotamian city-states operated in different ways, they often had similar institutions and infrastructures. For example, the ruler (known as king, prince or lord) generally lived in a palace surrounded by fortifications. Other buildings include a market (for trading goods) and temples and zigurats (for praying to and honouring the gods).

Reconstruction of a city-state (Babylon)

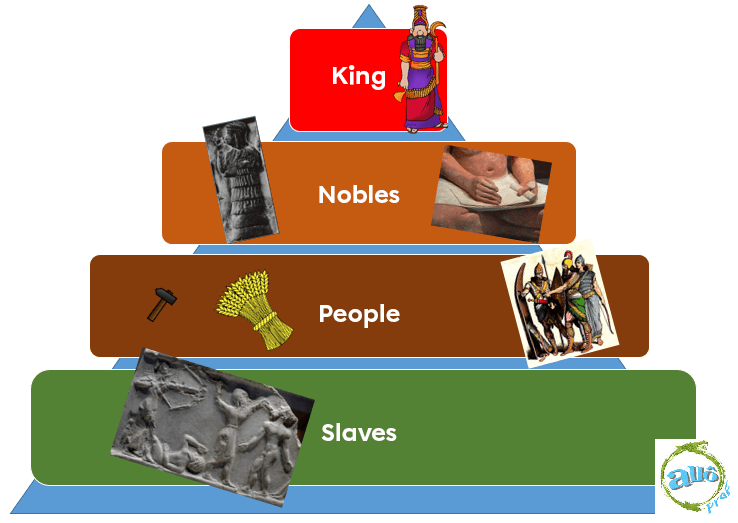

The population of Mesopotamian city-states was divided into groups based on their tasks and powers.

Image source: King / Nobles 1 / Nobles 2 / Commoners 1 / Commoners 2 / Commoners 3 / Slave

The king is the ultimate ruler of the city-state. He manages the army, construction and irrigation works, food surpluses and income taxes. In short, he holds absolute power because he is the representative of the gods on earth.

Mural of Nebuchadnezzar, King of Babylon

The nobles represent the social groups close to royalty. This group is made up of members of the royal family, priests, officials and scribes. The nobility assist the king in making decisions, carry out his orders and own the land. The scribes had a great deal of power because they could read and write.

Statue of a Mesopotamian high priest

The commoners or the people are made up of artisans, tradesmen, soldiers and peasants. All these people are illiterate (cannot read) and form the majority of the population. Artisans make the objects needed for everyday life. Traders sell goods at the market and import natural resources. Soldiers defend the territory and wage war abroad. Finally, peasants provide food for the population by cultivating fields and raising livestock.

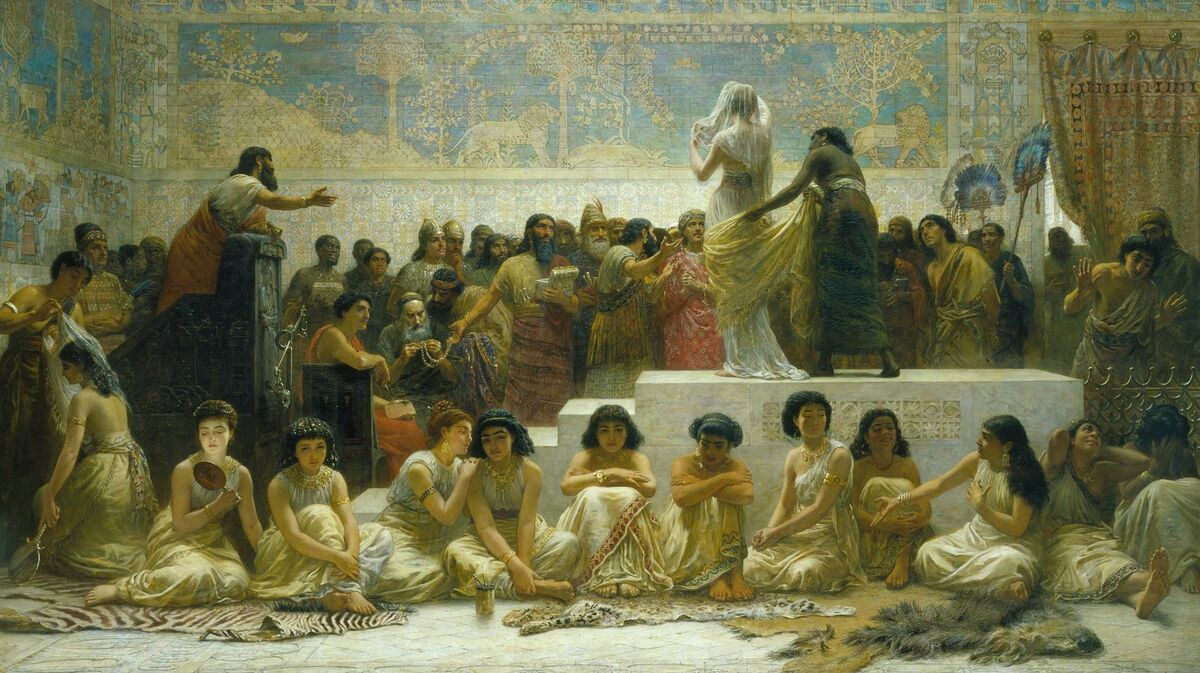

Painting depicting the commoners at a wedding in Babylon

Slaves were prisoners of war or people who had failed to repay a debt. They were used as workers in the city-state.

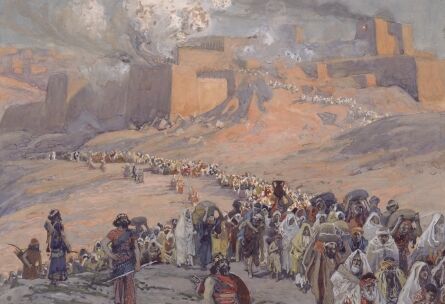

Painting depicting Babylonian slaves

With the emergence of increasingly populous city-states, there was a need to create regulations and laws and to ensure that they were known by the entire population. Around 1750 BC, a Babylonian king named Hammurabi developed a code of laws to ensure order in his city. This code, known as the Code of Hammurabi, contains almost 300 articles of law covering a wide range of areas: agriculture, the family, trade, property, and so on.

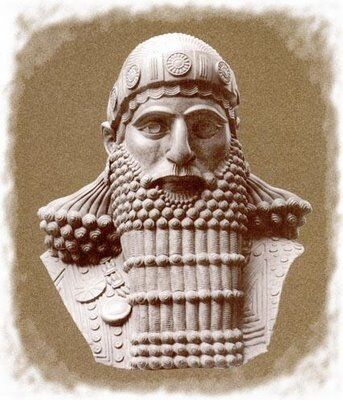

Bust of King Hammurabi

Stele inscribed with the Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi illustrates to all the inhabitants the laws to be respected and the consequences of not respecting them. This code corresponds to the law of Talion: ‘an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth’, as the following passage demonstrates:

If someone gouges out an eye of a notable person, he shall have an eye gouged out. If he breaks a bone of a prominent person, he shall have a bone broken.

This code makes a distinction according to the social classes to which people belong. The consequences for harming a nobleman are not the same as for a commoner.