Questions about Quebec’s political status became increasingly present in public debate from the beginning of the 1980s to the end of the century. The election of the Parti Québécois in 1976 strengthened people’s desire for political change in the Francophone province: the party’s leader, René Lévesque, promoted Quebec sovereignty. The Francophone province began to reconsider its status within the Canadian federation after several failed constitutional negotiations in which Quebec felt its rights were not being respected. Quebec nationalism grew, creating fertile ground for the advancement of ideas about sovereignty in Quebec. The Québécois therefore faced significant political decisions in the final two decades of the 20th century.

In 1980, four years after he was elected, René Lévesque held a referendum on sovereignty-association. The objective was to gain Quebec’s political independence while remaining economically tied to Canada. These economic ties meant maintaining the Canadian dollar, sharing the Bank of Canada and protecting trade with Canada.

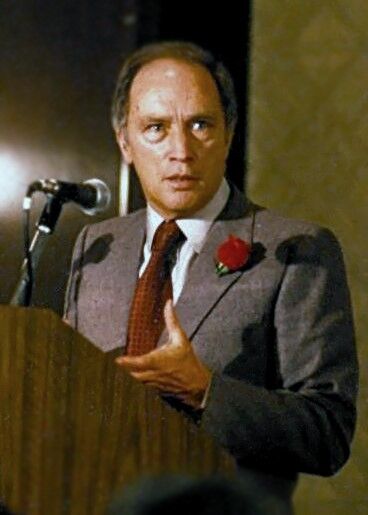

This proposal for Quebec voters led to many public debates, in which two factions clashed in a heated referendum campaign: the YES side (for sovereignty-association) and the NO side (against sovereignty-association). Pierre Elliot Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister at the time, wanted Quebec to remain a Canadian province. He campaigned for the NO side, in particular by proposing renewed federalism, which would show greater consideration for Quebec’s demands within the Canadian federation. As a result, the NO side won, with 59.56% of the vote.

A referendum is a vote in which citizens express their opinion on a measure proposed by the government.

In 1980, four years after he was elected, René Lévesque held a referendum on sovereignty-association. The objective was to gain Quebec’s political independence while remaining economically tied to Canada. These economic ties meant maintaining the Canadian dollar, sharing the Bank of Canada and protecting trade with Canada.

This proposal for Quebec voters led to many public debates, in which two factions clashed in a heated referendum campaign: the YES side (for sovereignty-association) and the NO side (against sovereignty-association). Pierre Elliot Trudeau, Canada’s prime minister at the time, wanted Quebec to remain a Canadian province. He campaigned for the NO side, in particular by proposing renewed federalism, which would show greater consideration for Quebec’s demands within the Canadian federation. As a result, the NO side won, with 59.56% of the vote.

The official logo of the YES side during the 1980 referendum-association.

The official logo of the NO side during the 1980 referendum-association.

In 1981, Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau tried to patriate the Canadian Constitution in order to gain more power in relation to the United Kingdom. In other words, he wanted the Canadian Constitution to belong to Canada rather than the United Kingdom. This way, Canadians would be free to make changes to it.

However, he could not achieve this without approval from the Canadian provinces, each one wanting to make sure its interests would be served within the Canadian prime minister’s constitutional plan. Pierre Elliott Trudeau planned several constitutional negotiations with the aim of reaching a consensus. In these negotiations, the provinces and federal powers debated the parameters of this new constitution.

These negotiations failed because with the patriation of the constitution, provinces were afraid they would lose power in relation to the federal government. Ultimately, eight provinces, including Quebec, opposed the prime minister’s plan. To overcome this gridlock, Pierre Elliott Trudeau planned informal meetings with each of the opposing provinces, except for Quebec.

These meetings allowed the Canadian prime minister to finally patriate the constitution in 1982 without Quebec’s approval. This meant that the Francophone province’s parliament never officially signed the new constitution. Many Québécois were not happy with this new agreement and relations between the province and Canada were negatively affected. Since then, Quebec has negatively dubbed this event the “Night of the Long Knives”.

Pierre Elliott Trudeau was Canadian prime minister from 1980 to 1984 and wanted to patriate the Canadian Constitution.

A new federal government was elected in 1984: Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative Party. This marked a new chapter in the relationship between Canada and Quebec. Mr. Mulroney started new constitutional negotiations so that Quebec could finally become a signatory.

Quebec’s newly elected premier, Robert Bourassa, agreed to resume talks. In 1987, the ten provincial premiers and Prime Minister Mulroney met at Meech Lake to come to a new agreement that would accommodate Quebec’s interests.

Although everyone present at Meech Lake agreed to a text including recognition of Quebec as a distinct society, the provincial parliaments of Newfoundland and Manitoba did not accept the compromise. Those two rejections meant that the Meech Lake Accord would never see the light of day.

Brian Mulroney succeeded Pierre Elliott Trudeau in 1984, promising in his electoral campaign to resume constitutional negotiations in order to include Quebec. He organized the Meech Lake conference for this reason.

This new failure in Canada-Quebec relations brought the question of Quebec identity to the forefront within the federation. In this context, Robert Bourassa launched the Bélanger-Campeau Commission in 1990 to plan for Quebec’s political and constitutional future.

This commission organized public consultations, recognizing that the political and constitutional status of Quebec needed to be redefined. To settle this question, in 1991, the commission recommended holding a new referendum on Quebec sovereignty, while inviting Ottawa to submit new constitutional offers that were more favourable to the province.

The Bélanger-Campeau Commission was not alone in recommending another referendum. The “Allaire Report” also released its own proposal in 1991 for a renewed relationship between Canada and Quebec. This report proposed signing a new constitutional agreement that would include Quebec’s demands. The report recommended holding a new referendum on sovereignty if no new agreement was signed between the Francophone province and the rest of Canada.

In 1992, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney tried once again to find a way out of Canada’s political crisis. He planned new constitutional talks in Charlottetown. The provincial government, Indigenous representatives and territory leaders were all at the negotiating table.

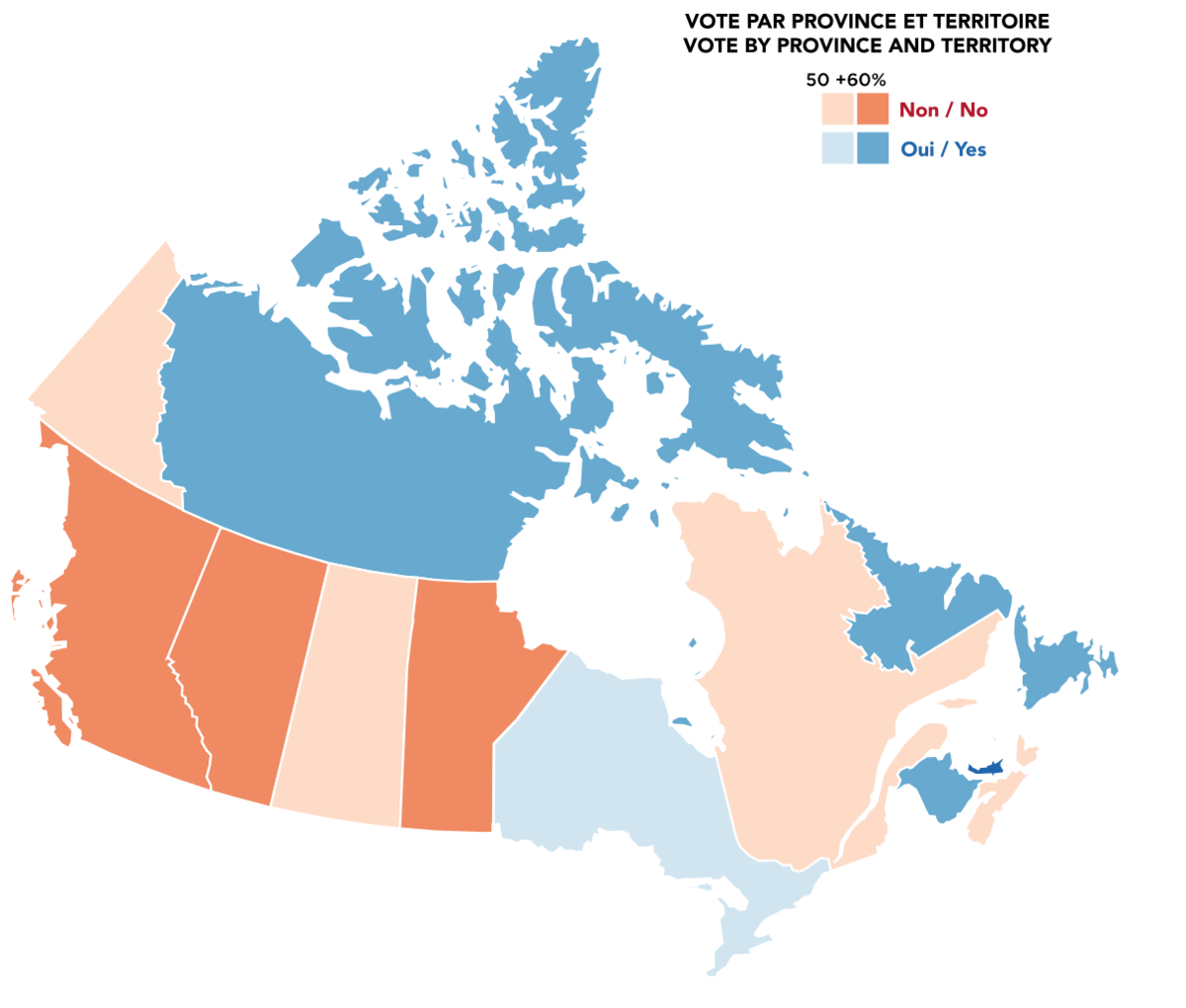

Once again, an agreement recognizing Quebec as a distinct society was signed. However, Brian Mulroney submitted it to the population for approval rather than to the provincial parliaments. The fate of the Charlottetown Accord was therefore decided by a referendum. Brian Mulroney experienced another failure when the accord was rejected by 56.7% of voters in Quebec and 54.3% of voters in the rest of Canada.

The Charlottetown Accord was approved by the Northwest Territories, Ontario, Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick. Conversely, Quebec, Nova Scotia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British Columbia and the Yukon rejected the accord. The vote was submitted to the population as a referendum.

After these many failed negotiations, the issue of Quebec’s sovereignty became more pressing than ever, and plans began to take shape both in Ottawa and Quebec City.

In Ottawa, the Bloc Québécois, a newly formed sovereignist party created to strengthen Quebec’s interests in the Canadian parliament, was able to get enough deputies elected to form the official opposition in Jean Chrétien’s new liberal government. Its founder, Lucien Bouchard, would lead this new political group for nearly five years.

In 1991, Lucien Bouchard founded the Bloc Québécois, a federal political party promoting sovereignty for Quebec.

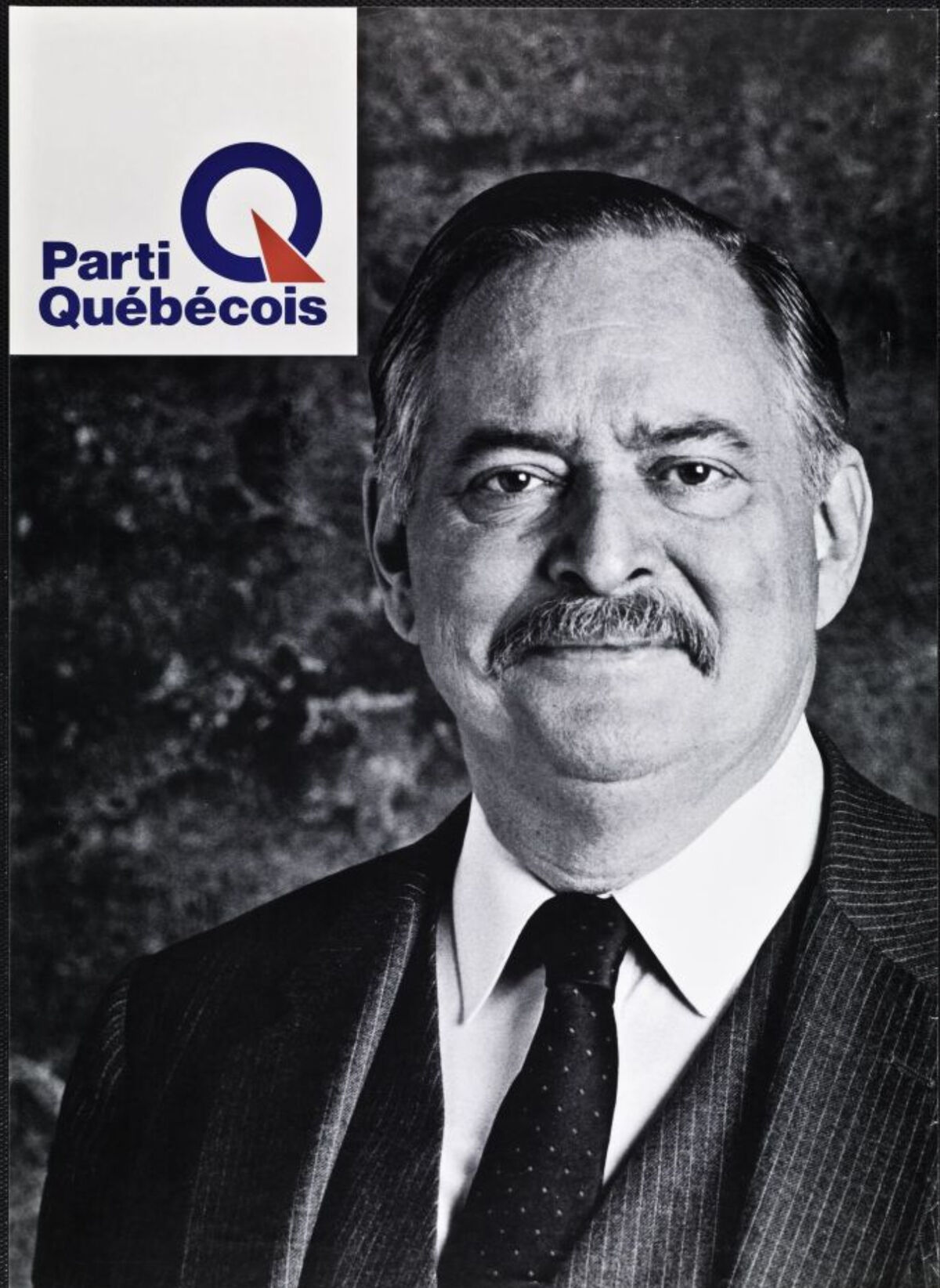

In Quebec, the idea of another referendum on sovereignty took shape when the Parti Québécois took power in 1994. This party was led by Jacques Parizeau. For Quebec’s new premier, there was no doubt that Quebec should once again address sovereignty in a referendum vote.

In 1995, the sovereignty referendum campaign was launched, once more pitting NO supporters against YES supporters. In the end, the NO side won in a narrow vote: 50.58% of voters rejected the proposal, while 49.42% voted yes.

Jacques Parizeau called a second referendum on Quebec sovereignty in 1995.

Disappointed with the results, Jacques Parizeau handed in his resignation the day after the vote. Bloc Québécois founding member Lucien Bouchard took his place. He became Quebec’s premier three months later.

Jean Chrétien adopted the Referendum Clarity Act in 2000 to ensure the legitimacy of referendums. The act specifies that the question citizens are asked must first be approved by the federal government to make sure it is very clear.

Later, Stephen Harper recognized Quebec as a distinct nation through a motion in 2006. However, no change was made to the Canadian Constitution.