The concepts covered in this sheet go beyond what is covered in secondary school. This is supplemental information for students who want to find out more.

Paris underwent many changes during the 19th century, from a medieval city to an inspiring modern city. As with other cities in the Western World, these changes were mainly caused by the Industrial Revolution. Paris attracted many newcomers from rural areas and from abroad. The urban territory gradually spread outside the city walls. This led to the creation of suburbs, which sprawled due to the lack of housing in the city and the arrival of new transportation methods, such as the train.

In 1801, France’s population stood at 29 million and made up 17% of Europe’s population with 5.1 million people living in urban centres. Urbanization made Paris the most populated city, with 1 million inhabitants in 1836. This number doubled in 1866 and eventually reached 3 million by 1886.

This rapid increase in the population of Paris came with its own set of problems such as impoverished newcomers, the creation of destitute areas both in the city and in the suburbs, overcrowding and lack of sanitation. Authorities quickly realized they needed to reform the city to adapt to this new reality.

The various French political regimes of the 19th century attempted to reform Paris, including Napoleon. The emperor wanted to make Paris the true capital of Europe. To do this, he planned to demolish the entire old town and improve the traffic flow. Napoleon was unsuccessful, but he did complete several projects. Napoleon’s urban planning consisted of both prestige and regulation. He wanted to make the city vibrant while regulating density and traffic. His projects included:

- Constructing new streets, footbridges and bridges

- Building canals and ponds

- Remodeling the Louvre’s façade and building new monuments, including the Arc de Triomphe

The initial urban planning effort carried out during the Restoration was done by the commission appointed to assess the city and to examine the city centre. The report mainly concluded that the old medieval centre was obsolete and generally despised by the authorities. There was disparity between the two banks of the Seine: the right bank had a wealth of new districts and new developments while the left bank was not developed. The report concluded that the city needed a coherent urban railroad network. The city had several train stations, but they were not connected to each other, nor to the city centre.

This led to the completion of numerous projects between 1815 and 1848, including the creation of 175 new roads. To build many of these new roads, property was expropriated, and houses were demolished to create enough space for them. However, the work was soon limited by a lack of financial resources and the laws that were in place at the time. The authorities refused to put the city into debt and stopped the work. The situation remained unchanged until the Second French Empire.

Napoleon III undertook numerous projects with the overall goal of improving society as a whole. This included adapting Paris to modern society. Napoleon III’s projects included connecting the railway stations, opening up the old districts, creating gardens in the city centre and building north-south and east-west intersections.

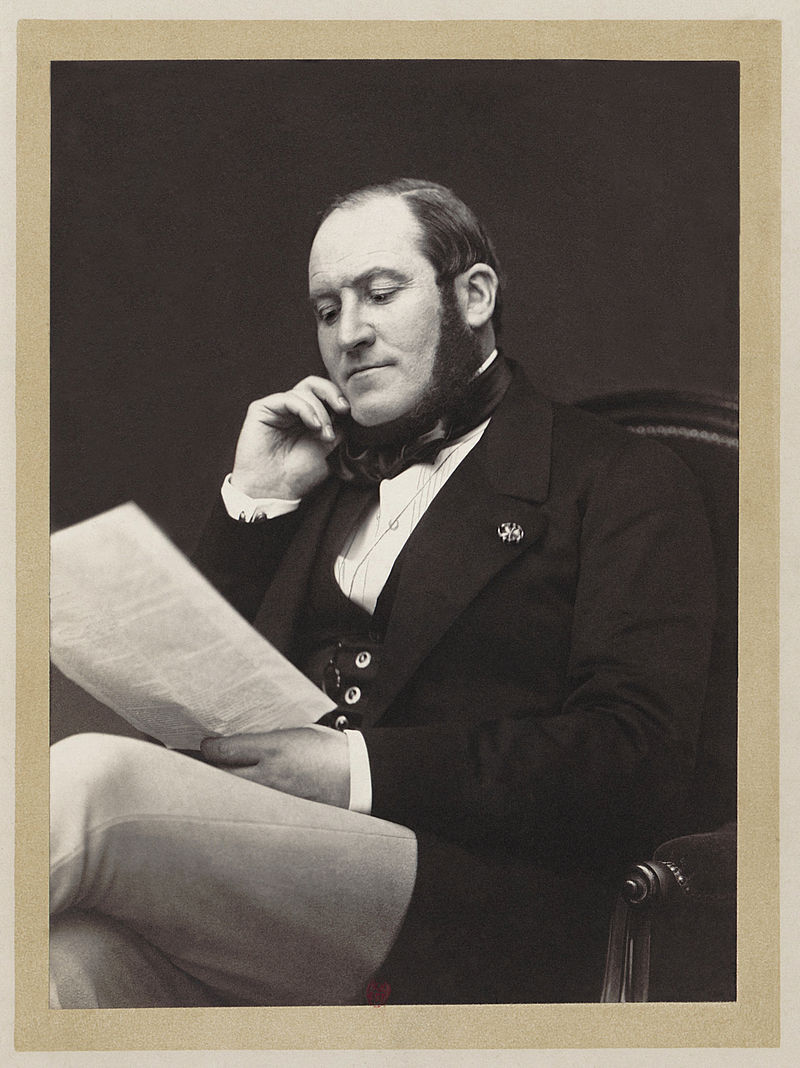

Napoleon III hired Haussmann as prefect in 1853. Officially, Haussmann didn’t come up with any new urban planning ideas but took over existing ones and organized them. This allowed him to develop an impressive urban reconstruction program. Haussmann created a network of major boulevards, ventilating the city and facilitating urban travel. In practice, this program provided the city with a more logical layout, which would be copied by many French and foreign cities. Haussmann borrowed the money to complete his projects from new financial institutions.

At the start, Haussmann wanted to gut the old Paris to reduce its density and spread the population more evenly across the city. He also set up a traffic network around the centre, including large squares at intersections, such as the Place de l’Étoile or the Place de la Bastille.

Haussmann also established 560 kilometres of sewer systems as well as aqueducts, large parks and gardens. He created new standards to ensure that new buildings were built using the same style. New monuments built during the Haussmann era included churches, the Palais de Justice, the Opera, the Bibliothèque nationale, the prefectures and the district town halls.

Haussmann’s work established regulatory urban planning and resolved several problems such as traffic flow, density and poverty in certain districts. He created better sanitary conditions, eliminated obsolete areas and standardized the city’s style.

Despite the popularity of Haussmann’s work, he received a fair deal of criticism, including the fact that he divided working-class districts with large boulevards. Many people believed this was intended to prevent workers from revolting and building barricades. Haussmann was also criticized for borrowing a lot of money to finance his work.

Although Haussmann’s work was criticized, it inspired urban planning throughout many Western cities until the early 20th century. Paris also demonstrated its modern character at the world’s fairs of 1844, 1855, 1867, 1878, 1889 and 1900. The Eiffel Tower was one of the most important symbols of the 1889 World’s Fair.

|

Year |

Population |

|---|---|

|

1836 |

1 million inhabitants |

|

1866 |

2 million inhabitants |

|

1886 |

3 million inhabitants |

|

1904 |

4 million inhabitants |

|

Country |

Urbanization rate |

|---|---|

|

France |

44% |

|

Germany |

62% |

|

Great Britain |

90% |