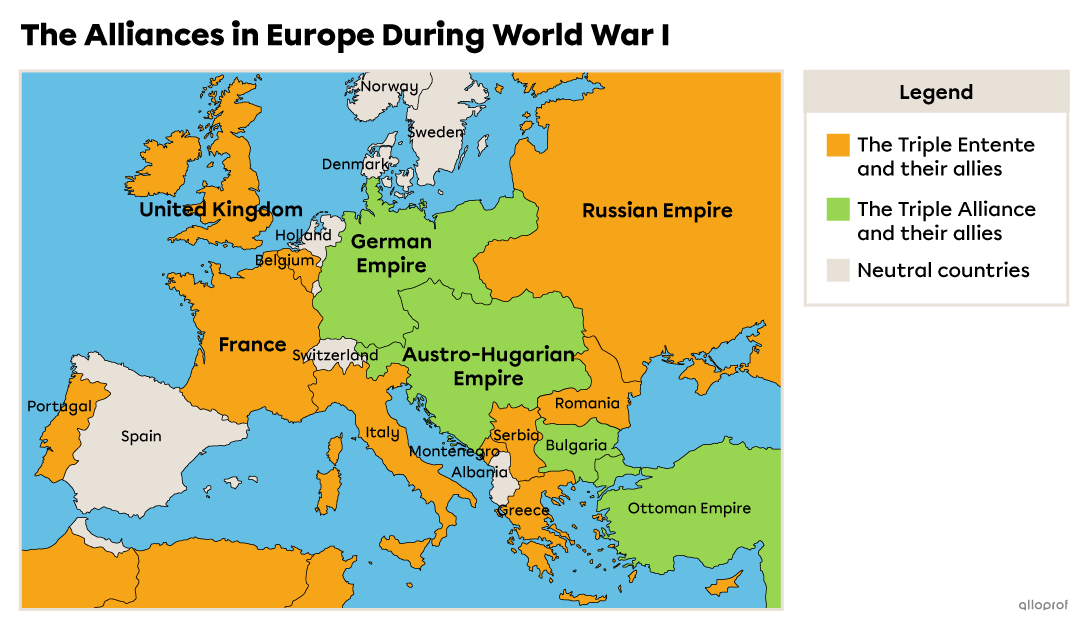

At the end of the 19th century, there was a lot of tension in Europe. Rivalries formed between world powers since some of them wanted the same territories. This led to some countries accumulating weapons, while nationalist feelings became more widespread. In these circumstances, alliances were created and two opposing blocs gradually emerged. On one side, Austria-Hungary, Germany and Italy made up the Triple Alliance and on the other side, France, Russia and the United Kingdom made up the Triple Entente.

The Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente were the two opposing blocs during World War I.

World War I was triggered when a Serbian rebel assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria-Hungary as he passed through Sarajevo. Austria-Hungary then declared war on Serbia, which was supported by Russia, and the various allies then began to mobilize one after the other. It was in 1914 that war was declared between the Triple Alliance and the Triple Entente.

Even from across the ocean, Canada was also affected by the conflict. As a British colony it had no control over its foreign policy, meaning it had to support the United Kingdom in times of war.

When the conflict broke out, industrialization had transformed traditional ways of fighting. The countries involved had to make sure that they had enough resources and equipment to both attack and defend themselves. While some had assumed the war would be over quickly, it lasted longer than expected and resources were running out. The European powers automatically turned to their respective colonies to obtain supplies and win the war. The colonies had to provide material and human resources to contribute to the war effort and support their mother country.

The European powers colonized new territories to obtain raw materials at low prices. During World War I, supplies from the colonies were a major strategic challenge.

The United Kingdom’s colonies were no exception. When the mother country went to war, the Dominion of Canada had to follow suit. While sending soldiers was optional, Canada had a duty to send materials to support the United Kingdom. To show his support for the cause, Prime Minister Robert Borden decided to send soldiers to Europe.

At the beginning of the conflict, the Canadian army was made up of just over 3000 soldiers and the navy had only two ships. Given the situation, recruitment centres opened all over the country and managed to gather 32 000 volunteers in a few weeks due to an enthusiastic population.

Robert Borden, a member of the Conservative Party, was the Prime Minister of Canada when the war broke out in 1914.

The first soldiers left Canada barely two months after war was declared. They trained in England first before being sent to the front lines in France in December 1914. Fighting took place in the mud, on a front that was practically immobile, with Canadians often used as shock troops by British generals, earning them a good reputation despite heavy losses.

German soldiers on the front lines had a good position that they firmly defended and their opponents had to find attack strategies that would force them to abandon their position. Both sides experienced minimal gains and increasingly heavy losses. Canadian troops joined British troops in Vimy on April 9, 1917, and won a major battle.

The 1917 Battle of Vimy Ridge was an important victory for Canadian soldiers.

At the beginning of the war, Canadians supported the mother country. The federal Prime Minister was given more power to more effectively manage military involvement in the war. The government then passed the War Measures Act, which gave it broader power to make decisions during wartime. This provision authorized the federal government to introduce levies and new taxes to finance the war.

During this conflict, the Prime Minister established the Ministry of Overseas Military Forces. Its purpose was to control the administration and management of Canadian forces on the battlefield and to give Canada more independence. This meant that Canada was in charge of Canadian soldiers, rather than the United Kingdom.

The war effort initially attracted many volunteers and unemployment decreased as many of those unemployed joined the army. In 1915, Borden promised to send 250 000 men to Europe to support the United Kingdom. In 1916, this number increased to 500 000. Given that Canada’s population at the time was 8 million people, it was a major challenge to get this many men to enlist.

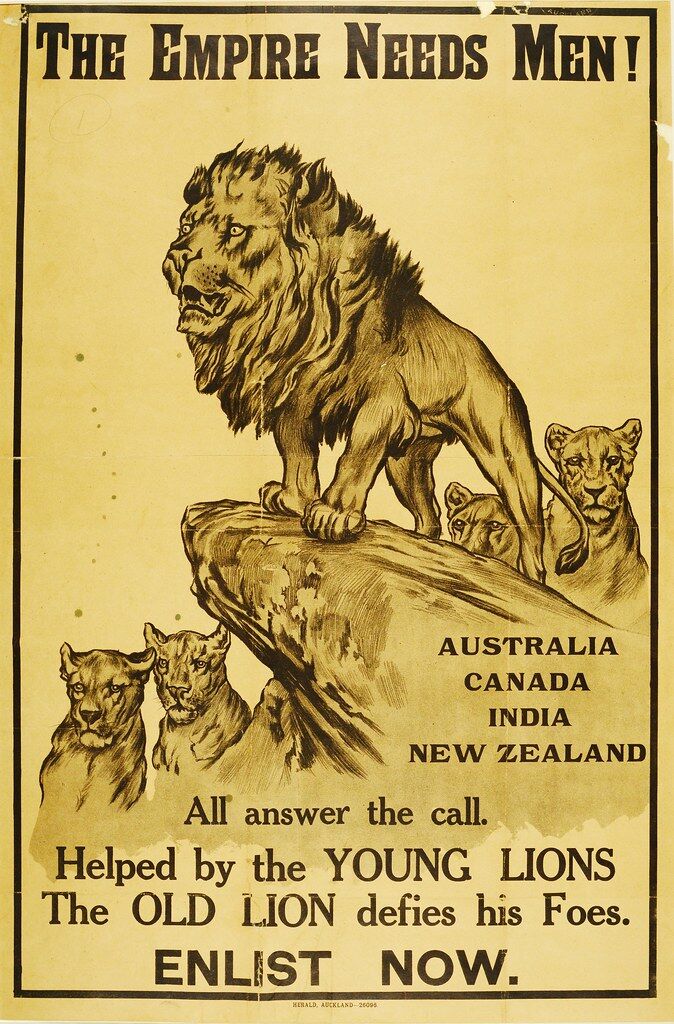

Many propaganda posters were distributed to convince men to enlist to fight in the war. In this poster, the United Kingdom is represented by an older lion that is supported by young lions, the colonies.

The initial enthusiasm gradually faded—despite many volunteers at the start of the war, they decreased across the country as the war continued. Many French Canadians refused to join the war effort because they did not feel like they were part of the United Kingdom. To fulfil his commitment, the Prime Minister proposed conscription.

Conscription is the state-mandated enlistment of all male citizens considered to be of fighting age. In some cases, conscripted men could request an exemption for various reasons, such as a medical condition. Others hid in camps or attics to avoid mandatory enlistment.

French Canadians voiced their dissatisfaction and some even started protests and riots. They believed that Canada was already sufficiently involved in the war by providing food and ammunition and there was no need to send more men.

Henri Bourassa and Wilfrid Laurier became the voices of French Canadians against conscription. They argued that Canadians should not have to fight for the United Kingdom but English Canadians saw the French Canadians’ refusal to help as an insult to the British Crown. The conscription crisis raised tensions between Anglophones and Francophones and caused a major divide between the Canadian people.

An anti-conscription protest held in Montreal on May 24, 1917.

The divide between those who supported conscription and those who were against it worsened during the elections. To increase support for conscription, Borden offered the right to vote to Canadian soldiers overseas, to women married to soldiers and to army nurses. His proposal worked, and he was re-elected in 1917.

On January 1, 1918, conscription officially came into force. Several exemptions were made, for instance, for farmers who had to produce food for the military. However, many of these exemptions were lifted throughout the year to send more soldiers to battle.

In 1915, the government’s military budget was the same as its total expenses for 1913—the government needed to find new financial sources to pay for the war and to boost the economy. It decided to issue victory bonds to taxpayers. Citizens who purchased bonds would lend money to the government to pay for war-related expenses and the government would pay citizens back the money invested, with interest, after the war ended.

Several advertising campaigns were used to encourage people to buy victory bonds.

Men were not the only ones sent to the front lines. Nearly 3200 Canadian women were sent to Europe. They were not allowed to fight, but served in the military as nursing sisters.

On Canadian soil, factory workers were needed to support the war effort by manufacturing goods such as uniforms and ammunition to be sent to the front lines. Since a significant portion of working-age men had been deployed to Europe, women were asked to contribute by taking their place in the factories of many industries.

To contribute to the war effort, women worked in factories that produced ammunition.

Nursing Sisters

Other women would contribute to the war effort from their homes, as they were encouraged to reduce the use of various products at home. First, the government imposed rationing—each family was given a number of stamps to buy certain products at the market. Food such as sugar, eggs, meat, chocolate and coffee were limited so that as many resources as possible could be sent to the front lines. In addition to limiting purchases, the government implemented several policies to reduce waste and reuse various products. These policies limited the production of new items so more resources could be sent to the soldiers.

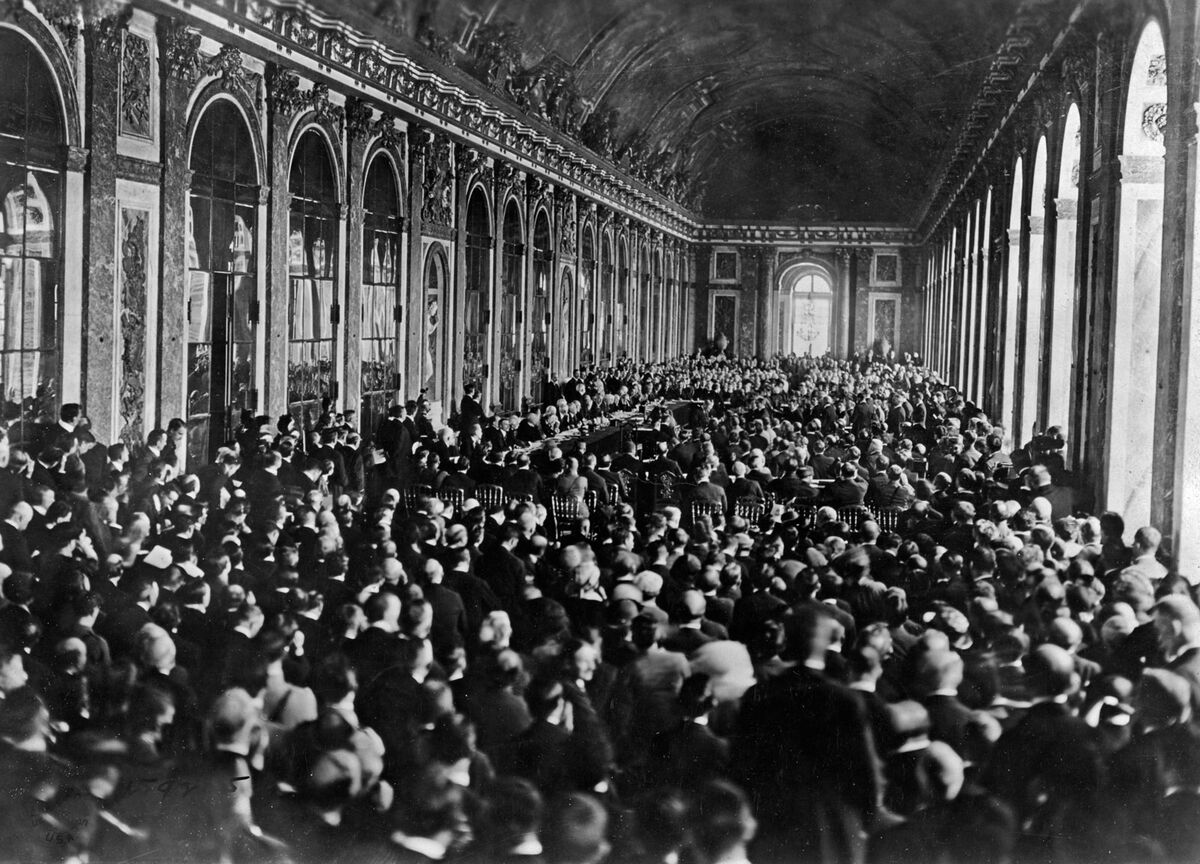

The final battle in which Canadian troops participated took place on November 11, 1918. The war officially ended on June 28, 1919, when the Treaty of Versailles was signed. In total, 60 661 Canadian soldiers lost their lives on the battlefield and many survivors came back wounded and shell-shocked.

Soldiers returning home from war struggled to adjust to civilian life. Some got their jobs back, but not all, as production decreased after the war ended. The government gave some veterans land and trained them for new jobs, but Indigenous soldiers were not eligible for government assistance.

With the signing of the Armistice, the major European powers created the League of Nations, the precursor to the United Nations that exists today. The League of Nations’ objective was to avoid another international conflict by promoting diplomatic relations between representatives of different countries. Canada was given a separate seat from the United Kingdom, thereby recognizing its independence.

The Treaty of Versailles was signed on June 28, 1919, and marked the end of the war and the Triple Entente’s victory over Germany.

The League of Nations aimed to promote communication between countries to prevent another world war.