The concepts covered in this fact sheet go beyond those seen in high school. It is intended as a supplement for those who are curious to learn more.

With the growth of cities and trade, townspeople began to defend their own interests and govern their cities themselves. While subject to lordly power, townspeople were considered subjects of the lord, just like peasants and vassals.

However, the increasingly wealthy city dwellers didn't want to submit to the same rules as the peasants, since they didn't live in the same way. In their view, the rules and functioning of the city should be decided by its inhabitants.

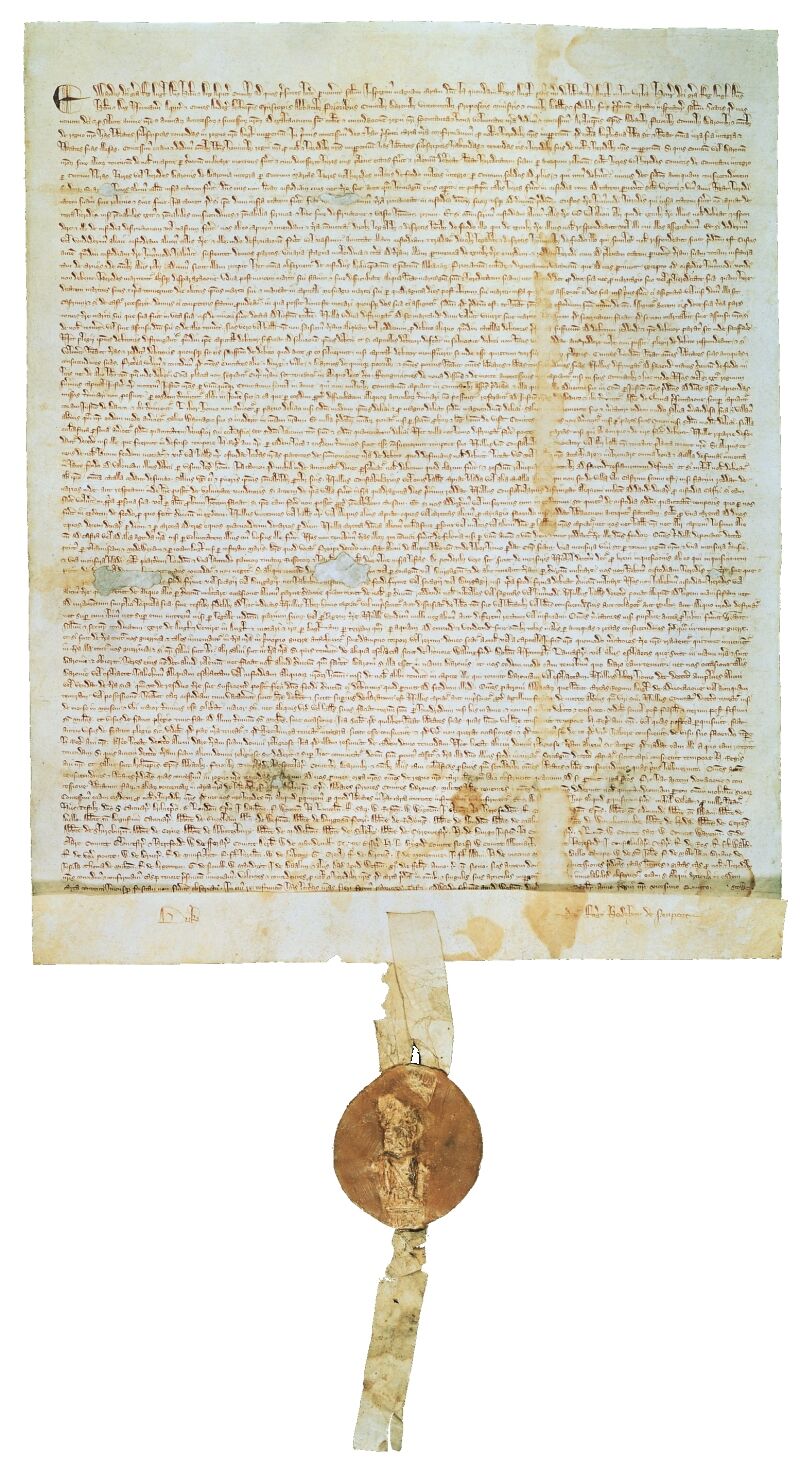

The Magna Carta of 1215 limited the king's power.

Many towns then began to claim rights from the lord or king, including the right to govern autonomously. The king and the lords acceded to the demands of the town community, which gradually became more important than the seigneuries.

Townspeople therefore joined forces to manage the town's affairs independently of the lord. The first autonomous towns, which took the name of communes, were truly based on power shared by the entire population.

Many lords granted rights and responsibilities to the towns. These rights concerned land management, defense of the city wall, construction of new buildings and control of merchandise. The granting of these rights gave townspeople total freedom to manage their own interests.

The communes passed laws and decided how they would operate. Since they had been granted autonomy, they were responsible for governing the city and all the functions associated with government. Citizens now had the right to vote to elect their representatives and magistrates, the right to decide on the city's internal rules and to determine the tax burden. In some regions, communes were given even more rights, such as the right to possess an army, elect a local government, mint the currency and manage internal and external politics.

By offering the management of the town to the entire population, the communes were managed as an oligarchy, in which the bourgeoisie and the lord shared power. The communes quickly gained in power, becoming real political and social powerhouses.

Montbrison in the Middle Ages

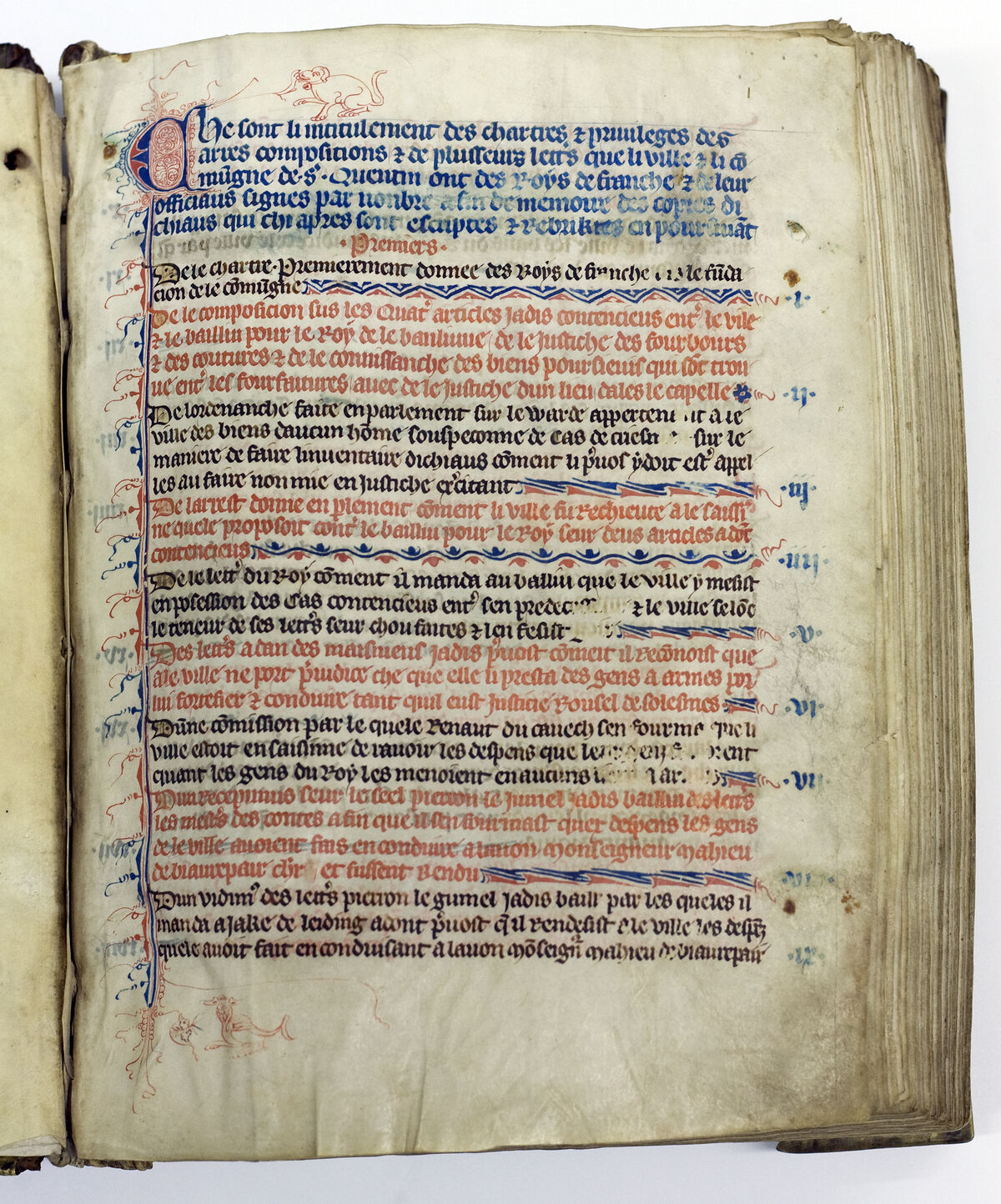

Townspeople took an oath to assist and advise each other, to ensure peace and security in their commune at all times. This oath had its origins in the communal charter, which described how the commune was to function. The primary aim was to eliminate conflicts and live in peace. Townspeople and the new communal power were to establish a regular social order in which solidarity and fraternity reigned. Some communes even created communal coffers to better finance charitable works and the civil service. The communal charter was made up of several statutes. These established the institutions the commune was to have.

Lhe communal charter of Saint-Quentin, dating from 1195

The first institution to be created was the Citizens' Assembly. As its name suggests, it brought together the entire population of the town. In some communes, the citizens' assembly was replaced by a broad council, made up of around 100 notables. These notables enjoyed a more prominent position in the communal hierarchy. Easier to assemble, this council had the power to make all decisions concerning the commune.

As communes evolved, the large council was also replaced by another, even smaller group: the college of aldermen (or consuls). Headed by the mayor, these aldermen were charged with specific responsibilities such as trade, salaries, justice, navigation and so on. Aldermen were elected by the population. Although all citizens could stand for election, the majority of aldermen were wealthy bourgeois .

In addition to the councils elected to make decisions, the communes had to organize and manage two other essential institutions: the militia, to protect the town, and the justice system.

Thanks to their wealth and strong political involvement, the bourgeoisie held virtually all the power in the commune. They were at the top of the social hierarchy. Whether they were notables or notables, the grand bourgeois were considered the meliores, i.e. the best in society. Although communes were defined as egalitarian political entities, real power lay solely in the hands of the meliores. The poorest not only had no power, they had no real right to contradict or interfere with decisions made by the bourgeois.

The commune's oath of equality had more to do with political equality between the lords and the communal power, i.e. the burghers. The control and administration of the town was assured by the patriciat: the wealthy families of the commune. The patriciat always made decisions that benefited them: regulations, taxes, rents, etc.

A charter of franchise was a deed by which a lord offered all the subjects of the seigneury the rights associated with the commune. For example, the charter of franchise of the commune of Moudon, Switzerland, established the following rules:

- The lord's right and obligation to preserve the rights and customs of the inhabitants;

- Respect for the lord's rights and honor on the part of the burghers ;

- Prohibition on arresting anyone within the town limits, unless he or she is a brigand, traitor, murderer or criminal.

It's difficult to describe the exact rules and functioning of the communes , since none of them really functioned in the same way. However, there are notable differences between communes located further north on the continent and those further south (southern France and Italy).

Communes in the south valued values and lifestyles closer to those of Roman antiquity. The urban elite was varied, comprising lords, merchants and bishops. Southern towns had their own lords and knights. Decisions relating to the commune were taken in agreement with the bishop and representatives of the population. These consuls were elected by the citizens.

Communes further north had a culture closer to medieval values. Indeed, their elites were mainly lords and members of the high clergy. These communes were also integrated into the seigneurial world, but benefited from a charter offered by the seigneur.

Founded in 1161, Avignon is a typical example of a southern commune. A trading city, Avignon was then one of the richest and most powerful towns in southern France.

The commune was presided over by a bishop, but the latter was subject to the authority of eight consuls. These consuls were elected by the population for a one-year term. The president and consuls were assisted by judges and masters. When important decisions had to be taken, the entire population was assembled.

As early as the 14th century, several conflicts broke out within the communes between craftsmen and rulers: economic power clashed with political power. Craftsmen and the poorer population, who held very little power, strongly criticized the abuses of the communes, giving rise to conflicts and confrontations. Conflicts also arose within the communes themselves. Wealthy families fought among themselves to gain control of the city and its riches.

At the same time, the peasants were beginning to revolt against these abuses. Their situation had not improved at all between the yoke of the lords and the domination of the bourgeoisie. What's more, the communes were engaged in fierce battles with each other for control of trade and territory.

In some cases, it was the kings and lords who regained control of the communes. The monarchy's return to power meant a loss of rights and political systems. The kings and lords wanted to put an end to the growing instability. This massive subjugation of communes, towns and the countryside enabled the kings to regain control of their territories and consolidate their central power.

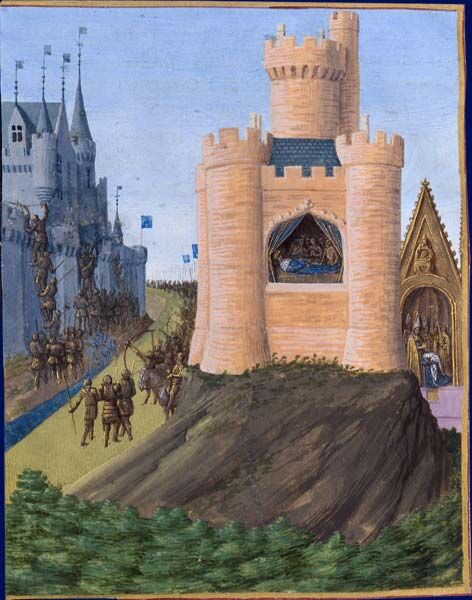

The siege of Avignon

The commune of Avignon is a case in point. After being besieged by the army of the King of France, it lost its autonomy. The king handed over authority to the count and ended all communal powers in 1251. Avignon is a good example of the decline of communes in the Middle Ages.