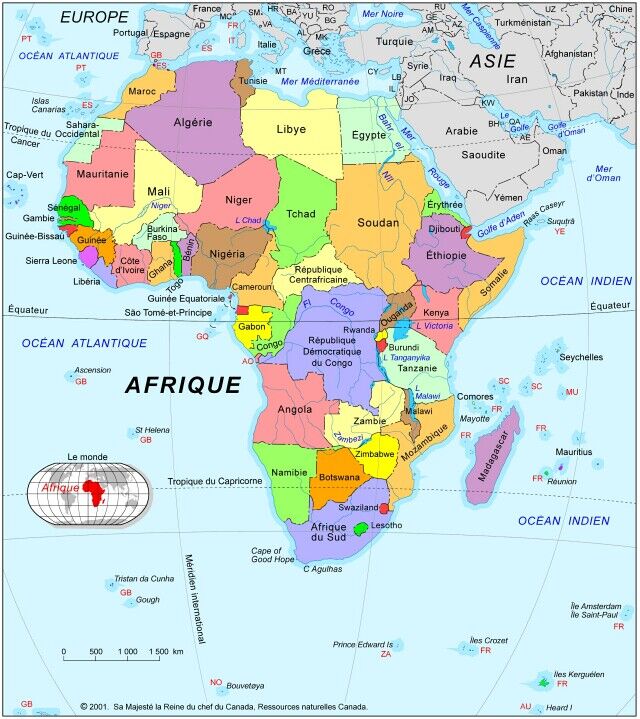

At the end of the 19th century, the European presence in Africa was limited to a few coastal trading posts or outposts, a few trading territories and a few permanent settlements. Most of the continent was still unknown to Europeans. The most frequented areas were limited to the coasts. The interior of the continent was still unknown and knowledge was based solely on hypotheses.

Note: Image in English coming soon.

In 1788, the African Association was formed in London (Association for the Promotion of Discoveries in the Interior parts of Africa). The main aim of this association was to travel the continent and explore the inner territories.

Before embarking on more in-depth exploration of the continent, the Europeans proceeded mainly with coastal explorations. The explorers set off in huge ships, equipped with large quantities of equipment, weapons and soldiers. The ships could hardly enter the interior and the Europeans had little contact with the local populations.

Land expeditions were organized in a completely different way. Individuals often set off alone or in small groups. Their progress across the continent depended entirely on interactions and exchanges with the different populations they encountered. As explorers often returned to the same point, these relationships were prolonged and repeated. Furthermore, the journey took place overland, where African heads of state exercised their power. The populations could therefore refuse the explorers the right of way. The explorers then had to prepare gifts for their hosts and adapt to the culture they were visiting.

Africa was visited long before the 19th century. Yet knowledge of the continent was fragmentary for many years. Until the 15th century, knowledge was based directly on the accounts of geographers and travellers such as Marco Polo. Some information also came from Arab contacts with sub-Saharan Africa. These interactions with Arab peoples did, however, lead to the development of fairly precise knowledge about the commoners or people of the Sahel, the Red Sea coast and the Indian Ocean.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, it was mainly Portuguese navigators such as Bartolomeo Dias who improved our knowledge of the coasts. After the Portuguese, many navigators from other European powers set out to explore the African coast. This type of exploration lasted until the end of the slave trade. Exploration of the interior of the continent began through the African Association set up in London. These explorations, which were more scientific in nature, also encouraged the colonization of Africa and the desire to bring civilization to the continent.

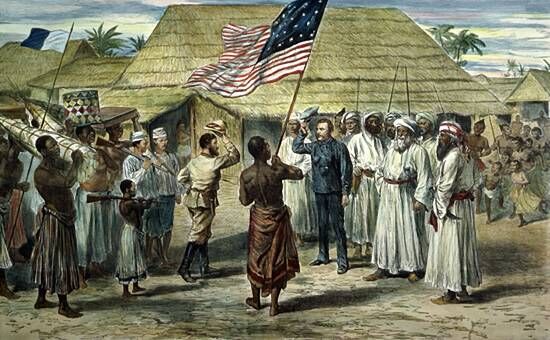

The first expeditions were supported by scientific societies and governments. They were also closely followed by the general public, who were keen to learn more about this still mysterious continent. The history of travellers quickly became intertwined with the history of colonization, as they often explored on behalf of a European power. Furthermore, these journeys increased knowledge of the continent and therefore knowledge of the natural resources available in Africa.

The missions assigned to explorers were varied: signing treaties with local populations, winning territory for a country, getting ahead of competitors, mapping a region, etc. As with colonization, the majority of expeditions were led by the British and the French.

Many explorers have gone off to conquer the unknown continent. The risks were enormous and the difficulties were always present: disease, insects, the wrath of certain populations, unknown routes, long distances, to name but a few.

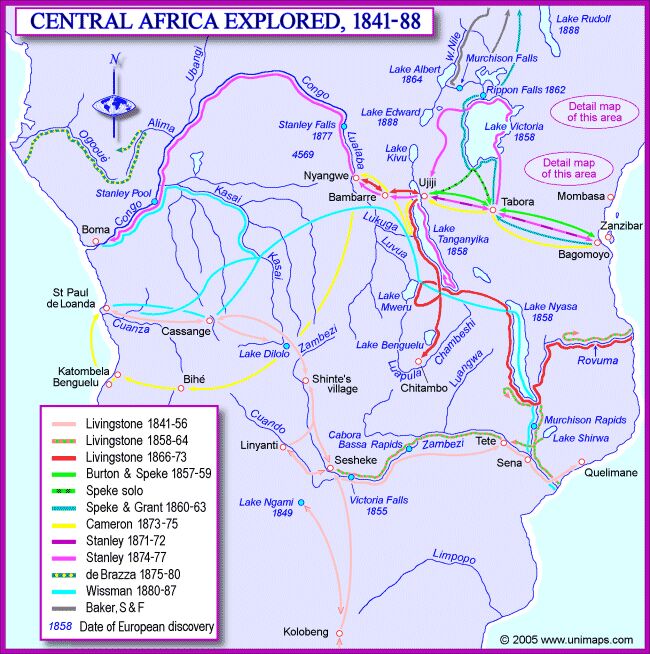

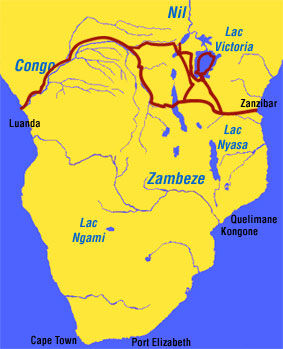

Here are two maps showing the journeys of some of these expeditions.

Note: Image in English coming soon.

Note : Image in English coming soon.

After a trip to South America, James Bruce embarked on a vast expedition to discover the source of the Nile. In preparation for his journey, he studied oriental languages in North Africa.

It was in 1768 that he set off on his great journey up the Nile. In 1770, Bruce arrived at Gonder in Ethiopia, after several adventures. He had not found the source of the Nile, but he did explore unknown regions. He published his travel accounts after returning to England in 1774.

After joining the African Exploration Association in 1788, Daniel Houghton prepared a voyage in which he wanted to reach the Niger from the Gambia. He also wanted to visit Timbuktu. After his departure in October 1790, we know that Houghton reached Farabana in Guinea. However, Daniel Houghton stopped sending news after 24 July 1791. He probably died ill or was murdered during his journey. His travel letters have nevertheless been published.

In 1795, Mungo Park set off for Gambia to explore the interior. During his journey, he visited several regions and was taken prisoner by the Moors. After escaping, he continued his journey up the Niger. He returned to England in a convoy of slaves and published his accounts of his travels.

In 1805, Park set off again on an official mission down the Niger. His journey was more unfortunate than the first, as he was attacked by a group of Haoussas and drowned. His travel notes were also published.

This French explorer set sail for Senegal in 1816. Having survived the shipwreck, he published an account of his shipwreck and learnt African languages. Ready for a second voyage, he explored the Cape Verde peninsula before sailing up the Senegal River in 1817. The following year, he returned to Senegal to continue his exploration. This time, he wanted to identify the source of the Senegal and travel to Gambia and Niger.

Hugh Clapperton made two trips to Africa. The first, in 1822, took him to the Hausa. On the second trip, he set off from the Gulf of Benin to discover North-West Africa. Unfortunately, all his journeyman died en route. He succumbed to dysentery during the course of his journey in 1825.

René Caillié spent a long time in Senegal and Guadeloupe. In 1824, after returning to Senegal, he lived there as a merchant and explored the Gambia on foot. He continued inland, posing as an Egyptian. He managed to visit Timbuktu and the Niger. In fact, Caillié was the first European to visit Timbuktu and bring back an account. He returned to Morocco using a caravan before returning to France, where he published his accounts before dying of an illness contracted in Africa.

A member of the London Missionary Society, David Livingstone, set off for southern Africa in 1840. He left to explore the continent in 1849. From then on, he undertook numerous journeys during which he discovered Lake Ngami and the Zambezi, among other places.

He was the first explorer to cross Africa from West to East. This journey, which began in 1852, lasted 4 years. In 1865, after several trips, he returned to Africa to explore Lake Tanganyika. He wanted to get to understand the lake better and continue his journey as far as possible. Along the way, he was abandoned by his men, who declared him dead.

Note: Image in English coming soon

In the meantime, Livingstone continued southwards, still near the shores of Lake Tanganyika. In 1871, Stanley set out in search of him. The two explorers met before continuing their expeditions.

Livingstone died of dysentery in 1873. All through his travels, he was trying to put an end to the slave trade in Africa.

Burton was an employee of the East India Company, so he travelled widely and published accounts of his travels. Later, he even managed to visit Mecca posing as an Afghan. He also made several trips with John Speke, during which they visited Harrar.

Burton's most famous trip was to the Great Lakes of Africa. Preparations for this trip began in 1836. Burton and Speke wanted to determine the exact position of the lakes, study the geography and commercial possibilities of the area and find the sources of the Nile.

Exploration began in 1857 and the two explorers discovered Lake Tanganyika, but they did not reach the end of it. Burton was incapacitated by fever, so Speke continued the journey alone. He discovered a second lake, which he named in honour of Queen Victoria. Believing he had unearthed the source of the Nile, Speke returned to Burton. Unfortunately, as Speke's evidence was insufficient, the two men fell out, putting an end to their collaboration. Burton did not stop exploring after these incidents, and during his lifetime he climbed Mount Cameroon, served the King of Dahomey and explored the Gold Coast, Guinea and Morocco. During all these journeys, he produced numerous geographical works.

Before setting off to discover the African continent, John Speke had served in India, where he was able to take part in excursions to Tibet and the Himalayas. In 1854, he set off on an excursion with Burton. Unfortunately, the two collaborators fell out during the trip, during which Speke was convinced he had found the source of the Nile. Speke went back to Africa in 1860 with James Grant to verify his hypothesis about the source of the Nile. The two men reached the Nile after several difficulties, but the hypothesis had been confirmed. They attempted to sail down the Nile on their return journey, but had to turn back because of hostilities. On their return to Europe, Speke and Grant shared their discovery with great success. They also published an account of their journey.

Note: Image in English coming soon.

Barth's first major voyage was around the Mediterranean. Barth had the opportunity to visit the coasts of France, Spain, Morocco, North Africa, Lower Egypt, Palestine and so on. After this trip, Barth wanted to take part in an expedition to Africa. Moreover, his aims were not just scientific: he wanted to abolish the slave trade and establish trade relations on behalf of Germany.

He left in 1850 to discover the Aïr. He was favourably received by the Sultan of Kouka. Barth continued his travels, visiting Timbuktu among other places, before returning to Marseille in 1855 and publishing his travel accounts.

Even as a young man, Henri Duveyrier knew he wanted to make scientific voyages to Africa. In fact, it was in 1857 that he made his first trip to Algeria. In May 1859, he set off to explore the Sahara. His trip lasted until 1861. On his return, he published detailed maps of the Sahara and travel accounts, all of which became very popular.

Note: Image in English coming soon.

A lifelong traveller, Samuel Baker took part in elephant-hunting expeditions in Ceylon in 1845. Not only did he hunt, he also wrote two volumes about the country and its inhabitants. In 1861, he embarked on an expedition to Cairo during which he attempted to discover the sources of the Nile. He even went to meet Speke.

During this trip, he studied and mapped the tributaries and the entire hydrography of the region. Despite the success of Speke and Grant's discovery, he wanted to take his journey further, but was rebuffed by the slave traders. He did, however, discover Lake Albert. On his return, he dreamed of launching a vast movement to suppress the slave trade. He worked hard on this mission, but it was an arduous task. He left the mission in the hands of collaborators before leaving Africa.

This British traveller spent a fair amount of time in New Orleans and the United States. He became a journalist for the New York Herald. He was sent as a journalist to Turkey, Abyssinia and Spain. In 1870, he was sent in search of David Livingstone, whom he found on the banks of Tanganyika. After his return to England, Stanley was given the task of leading other expeditions to Central Africa. In 1874, he set off again for Lakes Victoria and Albert, and also travelled down the Congo River, before returning to England in 1878. In 1879, he left again with the challenge of developing trade along the Congo, founding numerous trading posts or outposts as well as the Congo Free State.

After his many travels, he gave many lectures in America and Great Britain before settling permanently in England, where he was a member of parliament.

Note: Image in English coming soon.

In 1872, Verney Camron went on an expedition to Africa. Like Stanley, Cameron wanted to find Livingstone and help him. He did not find Livingstone, but he did explore the entire southern part of Lake Tanganyika. On the West coast of this great lake, he discovered a large river which he followed. In 1875, after travelling more than 5,000 kilometres, he arrived in the Congo. Cameron went on to make further expeditions to India and the Gold Coast.

This Italian joined the French navy, for which he carried out a number of missions in Africa, exploring the Gabon and Ogooué rivers and discovering the tributaries of the Congo. On his return to Europe, he informed Stanley of his discoveries. He then left again for the Congo, which he made a French protectorate in 1880. He also founded a station on the river, which became Brazzaville. On the same trip, he also explored Gabon, where he founded a number of stations.

By June 1882, Brazza was back in France and receiving a warm welcome. At the time, there was a great deal of jealousy between Brazza and Stanley. Brazza was very popular and took advantage of the scientific nature of his explorations to praise their merits. However, Stanley's discoveries were far more important.

Throughout his expeditions, Brazza's main concern was to avoid any conflict with the natives. Thanks to his knowledge of the continent, Brazza was sent to the Berlin Conference as a technical adviser. During another expedition, he governed the colony of Gabon. However, he was relieved of his duties. His last trip was in 1905, when he was due to return to Gabon to investigate the people who had removed him from his post. He never returned to Europe, dying on the way home.

Louis-Gustave Binger volunteered for a mission to Dakar in 1882. He carried out this topographical mission on the upper river. During his years of exploration, he explored the countries between Senegal and Niger, studied the route of a railway and drew up a map of French settlements in Senegal.

In 1887, Binger set off again to explore the lands from Niger to Guinea. In over 2 years, he covered 400 kilometres. The book of his journey was subsequently published, in which he stated: ‘We believe that State intervention will always be fatal’. After carrying out another mission to delimit the Ivory Coast, he was appointed governor of the colony. In 1897, he was appointed Director of African Affairs at the Ministry of the Colonies. Louis-Gustave Binger died aged 80.

This French soldier made his career in Africa. One of his missions, in 1896, took place in the Congo and on the Nile. His aim was to challenge British hegemony on the Nile and establish a French protectorate in southern Egypt. This mission only served to increase the tensions that already existed between France and England. In fact, British soldiers imposed a blockade around the French forces. It was only in January 1899 that the two parties reached an agreement: the French army had to leave, unable to stand up to the British army.

1768: James Bruce travels up the Nile to Ethiopia

1788: Formation of the African Association

Daniel Houghton travels to Niger

1795: Mungo Park visits the Gambia

1805: Mungo Park descends the Nile

1817: Mollien explores Cape Verde and Senegal

1822: Hugh Clapperton visits the Haoussas

1824: René Caillié visits Senegal and Niger: first European to visit Timbuktu

1852: Livingstone crosses the continent from west to east

Burton and Speke explore Lake Tanganyika

1860: Speke and Grant travel to the source of the Nile, in the Great Lakes

1861: Duveyrier returns from exploring the Sahara

1861: Baker discovers Lake Albert

1870: Stanley goes in search of Livingstone

1874: Stanley explores Lake Albert and Lake Victoria

1875: Cameron travels 5,000 kilometres from Lake Tanganyika to the Congo

1879: Stanley founds the Congo Free State

1880: Brazza makes the Congo a French protectorate

1887: Binger explores the territory around Guinea and Niger

1896: Marchand attempts to establish a French protectorate in the Congo, near the Nile.