Nationalism is an approach that aims to advance or defend a nation.

With the political tensions of the 1830s, nationalism became very politicized. The Parti canadien (later the Parti patriote) defended the Canadien nation and the concept of an independent Lower Canada grew in strength. After 1840, the cultural side of the French-Canadian nation (language, religion) was paramount because this represented the nation’s legacy. After 1867, tensions between English- and French-speaking Canadians (the Métis rebellions, the Conscription Crisis of 1917, etc.) revived French-Canadian nationalism, which implied turning away from the British Empire.

Honoré Mercier, Premier of Quebec from 1887 to 1891, supported Quebec’s autonomy from Canada and came to the defence of the French-Canadian nation. In 1885, he gave a nationalist speech at Champ-de-Mars about the hanging of Louis Riel, who led the Métis rebellions.

Lionel Groulx was another ardent French-Canadian nationalist in the early 1900s. The historian and professor leaned towards a more conservative nationalism, centred around family and working the land. Those ideas were spearheaded in newspapers such as Le Nationaliste and in the journal L’Action nationale.

Lionel Groulx had serious concerns about preserving the French language and the Catholic religion and in 1922, he published a book called L’appel de la race that praised Catholic and rural ideals.

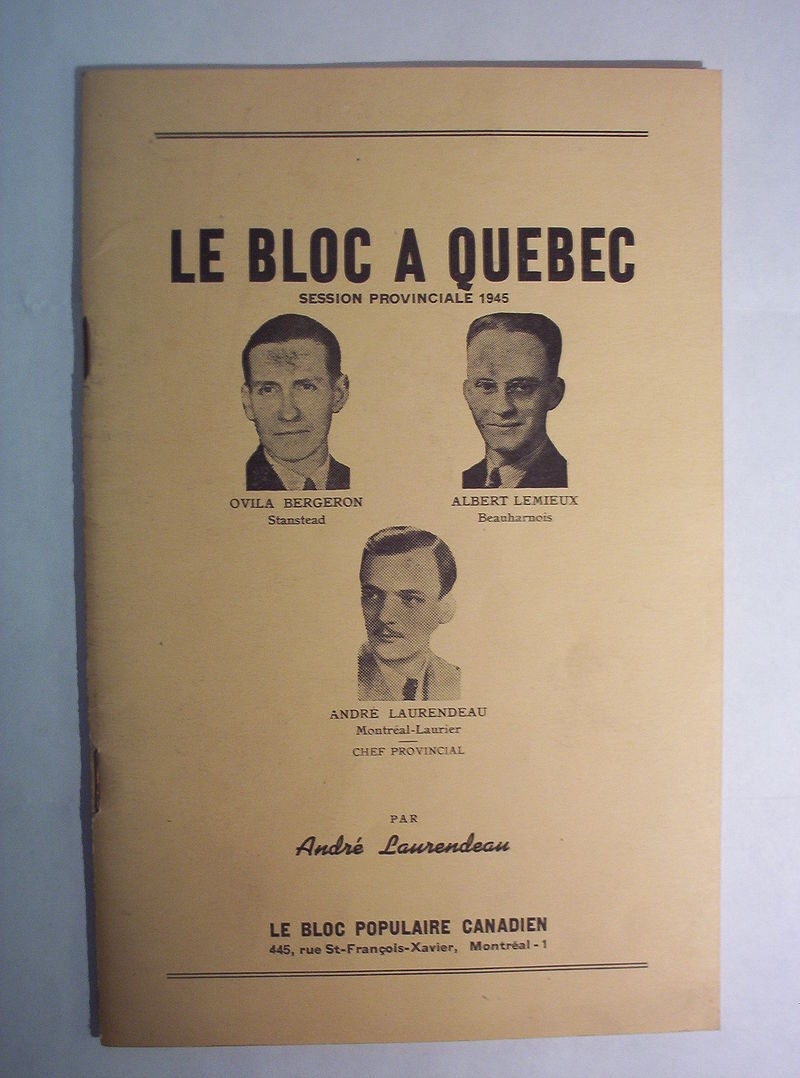

The Bloc populaire canadien, a provincial and federal political party, campaigned for Canada’s independence from the United Kingdom and for Quebec’s autonomy from Canada. Founded in 1942 by anti-conscriptionists, this party was active until its provincial leader, André Laurendeau, resigned in 1947.

Brochure of the Quebec section of the Bloc populaire canadien in 1945