Indigenous peoples consider getting older as a sign of wisdom. This is why the council of elders was made up of the oldest members of Indigenous groups and oversaw important decisions for the whole community.

For example, it set out the rules clan members must follow and decided whether enemies should be confronted. Since each council member was seasoned and wise, their opinions were greatly valued and in most nations, the council of elders was also responsible for choosing the chief.

A council of elders meeting

Source: Haudenosaunee Council Discussions [Painting], Parker, L., (n.d.), The Canadian Encyclopaedia, (URL). Rights reserved*[1]

The qualities needed to become a chief and the chief’s role differed from one language family to the next. For Inuit and Algonquians, two nomadic families with a patriarchal social structure, the chief had to be a skilled hunter capable of keeping the clan safe. His important responsibilities included deciding when to find a new camp and choosing a place with enough food.

The Iroquoians’ sedentary way of life fostered a system focused on dialogue and compromise rather than survival. Their civil chief was appointed based on courage, eloquence and powers of persuasion, with the council of elders making the big decisions. The chief’s role was to explain to council members why an opinion was a good one, and the chief, not the council, represented the village when it was time to communicate with other nations.

In this language family, it was not uncommon to have another chief known as the war chief. This leader was selected based on past exploits. This chief’s role was to lead fellow members if a war was declared.

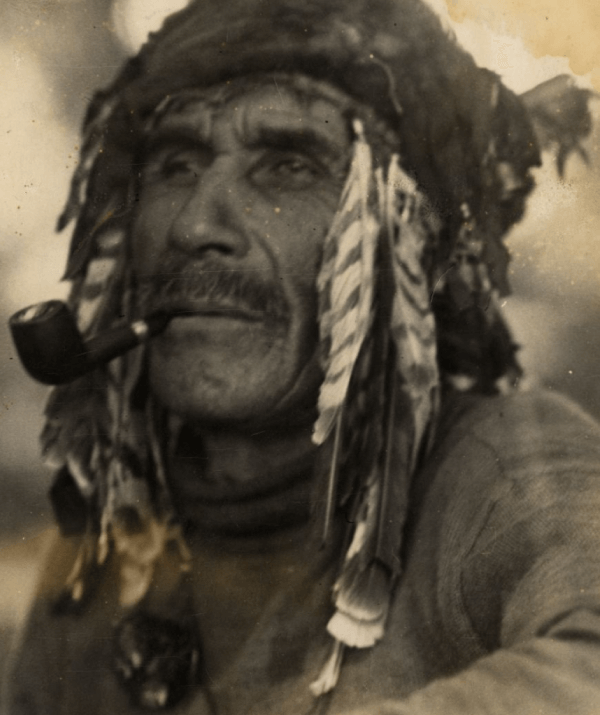

This picture was taken in 1920.

Source: Chef iroquois en habit traditionnel [Photograph], Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, circa 1920, (URL). Rights reserved*[2]

For Indigenous peoples, the world has three dimensions: the sky, the earth and the underworld. The sky is linked to spirits and the Great Spirit; everyday life takes place on earth; while the underworld is for the spirits of the dead. The wise and enlightened spiritual guide or healer established connections between the three dimensions and interpreted spirit messages for the tribe. For healers and spiritual guides to be credible, they needed to make accurate interpretations and predictions. Only those that had gained credibility in their community could be members of the council of elders.

The term shaman has often been used by Europeans to describe spiritual leaders in Indigenous communities around the globe. When referring to Canada’s First Nations, the terms employed are healer or spiritual guide.

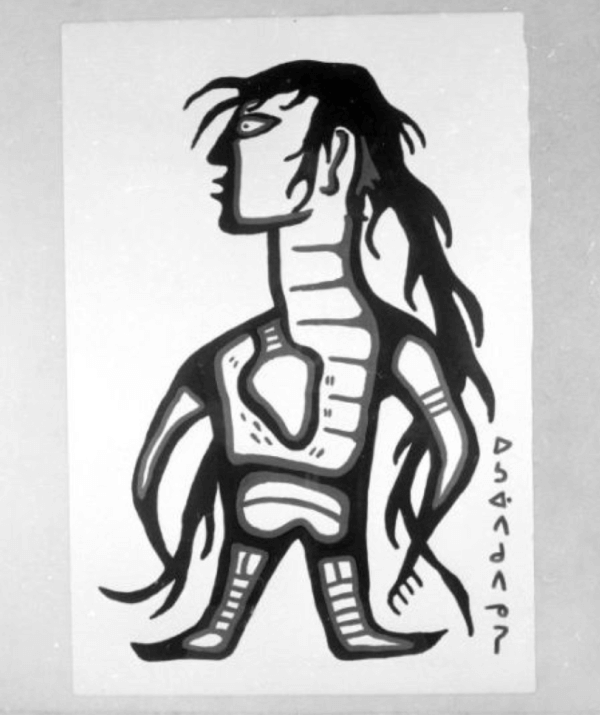

This is an example of a representation of a spiritual guide in Indigenous art.

Source: Photographies d'art autochtone prises au musée d'Art contemporain de Montréal [Painting], Szilasi, G., 1966, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. (URL). CC BY-NC-ND 4.0[3]

Indigenous peoples wanted to understand their place in the universe. Their understanding of the world was based on animism, the belief that all parts of nature, living and otherwise, have a spirit. They also created several myths and legends in an effort to explain mysterious phenomena and how the world was created.

Représentation de la légende selon laquelle le monde s'est formé sur le dos d'une tortue géante

Depiction of an Iroquoian legend of little men, first published in 1917 by the American Book Company.

Source: Powers, M. (2007). Stories the Iroquois Tell Their Children, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22096/22096-h/22096-h.htm#Page_195.[4]

Since writing was not part of traditional Indigenous culture, knowledge, myths and legends were passed along orally. Oral tradition was paramount in maintaining lifestyles and sharing knowledge, and young people learned chants, dances and myths by listening to them and participating in ceremonies.

In Indigenous learning models, education did not take place in a school system. Rather, children learned hands on. Parents took care of their own children, but the entire village was responsible for their education. Children were never ordered around or physically punished for misbehaving. Instead, adults encouraged them and congratulated them for good deeds. Although children had a lot of freedom, gaining recognition motivated them to demonstrate their bravery and skills as well as to help the village run smoothly.

For Indigenous peoples, if someone found more food than they needed, they had a duty to share the surplus with group members who struggled to find food. This meant that children, the elderly and the sick were always looked after.

Given this generosity, giving gifts and counter-gifts was common. If offered something such as a handmade object, clothing, food or a tool, the recipient had to find something of equal value to give in return. Most Indigenous nations fulfilled this moral duty of giving counter-gifts, but it’s important to note that this custom was not mandatory. They essentially exchanged, or rather bartered.

Although the two concepts appear similar, there is an important difference between the notion of bartering and that of giving gifts and counter-gifts.

Bartering is an agreement between two people to make an exchange—a deal is made.

With gifts and counter-gifts, one person gives to the other out of generosity and a desire to help that person. The person who receives the gift returns the favour out of moral duty.

The First Nations Great Summer Gathering takes place every year in Mashteuiatsh in Lac-Saint-Jean.

-

Parker, L. (n.d.). Haudenosaunee Council Discussions [Painting]. The Canadian Encyclopaedia. (URL).*

-

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. (circa 1920). Chef iroquois en habit traditionnel [Photograph]. (URL).*

-

Szilasi, G. (1966) Photographies d'art autochtone prises au musée d'Art contemporain de Montréal [Painting]. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. (URL). CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

-

Powers, M. (2007). Stories the Iroquois Tell Their Children, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/22096/22096-h/22096-h.htm#Page_195.

*Content used by Alloprof in compliance with the Copyright Act in the context of fair use for educational purposes. [https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-42/page-9.html].