The concepts covered in this factsheet go beyond those seen in secondary school. It is intended as a supplement for those who are curious to learn more.

Before the period of industrialization, Germany was not yet a united country. It was not until 1815, at the Congress of Vienna, that 39 states came together to form the new German Confederation.

The development of the country was easier following this union, as the leaders had real control over the various regions.

Taking the concept of unification a step further, the leaders also unified the German economy. The first economic measure was taken in 1834 with the Zollverein, a free trade zone within the Confederation. This economic agreement encouraged trade between each of the confederate states, thereby boosting German trade. To make trade even easier, in 1857 the German Confederation adopted the Prussian thaler as its currency. A few years later, in 1871, the German mark took on this role. Germany's economic and industrial development was greatly boosted by these measures. The government introduced a protectionist administration to protect internal trade.

At the beginning of the 19th century, German society was still organised around feudalism: peasants were enslaved and paid rent by working on seigneurial land. As the land was divided up into small holdings, the modes of production were still traditional. It was between 1815 and 1860 that farmers in Germany took on board technical innovations in agriculture. It was during this period that productivity increased, and the population also grew.

By 1815, agricultural growth was booming. This rapid growth was partly due to the innovative attitude of landowners, who did not hesitate to invest in new technologies and new modes of production. By 1850, agricultural innovations were increasing in Germany, complementing British imports at the turn of the century. Germany quickly made its mark in the chemical industry. This specialisation enabled the country to become a leader in fertiliser research.

Throughout the process of industrialization in Germany, the state continued to play a protectionist role, taking a number of measures to protect German industrialists. For example, the German state promoted the expansion of the railways, facilitated the formation of large companies, adopted protectionist economic measures and supported vocational training. The role of the state had a major impact on industrialization. Germany was the first country to provide social protection, health insurance and accident insurance for workers.

Industries were relatively slow to develop in Germany before 1850. This slower pace can be explained by the great disparity between each industrial area. What's more, in technological terms, Germany was lagging behind and dependent on Great Britain and even France. The first major factories were set up in 1850. This marked the beginning of modern industrial activities such as cotton mills and the steel industry. It was also the start of a phase of more rapid industrialisation.

The industries relied in part on the strong merchant tradition of the northern ports and the support provided by the State. By 1850, a third of the German workforce was working with machines. It was also at this time that the Germans developed their chemical industry. In the textile sector, work was still done by hand. However, innovations in chemistry led to a boom in this sector, with the creation of a number of textile dyes. Innovations in the textile sector were largely inspired by the British model. German manufacturers built and imported various machines. The introduction of mechanisation led to the bankruptcy of a number of craft businesses.

Between 1848 and 1870, Germany managed to catch up with France in terms of industrial development. By the end of the period, two-thirds of the population were employed in the industrial sector. Chemistry was still the most important economic sector. After 1870, large companies gained in importance and played a key role in industrial activity.

Although the railway played a less important role in the country's development than it did in the United States, this new mode of transport had a considerable impact on German industrial development. Rail connections were quickly established between the various factories and industrial centres across the country.

The first railway line was completed in 1838, linking Berlin to other industrial centres. As well as helping established businesses, this new connection encouraged Berlin's industrial development. Many entrepreneurs ventured into the railway industry because they saw it as a great business opportunity.

The financing of industry in Germany was not organised along the same lines as in Great Britain. In fact, British industrial financing was mainly based on capital investment on the stock exchange. In Germany, investment tended to come from associations between banks and companies. This form of financing created a high concentration of capital within German borders, with virtually no investment abroad. The strength of industry was thus closely linked to economic strength and national power. The emergence of industry led to strong development of the big banks. The German economy was now oriented towards contemporary capitalism.

The transformation to a capitalist, individualist economy did not happen overnight. Just a few years before the industrialisation of Germany, society was still based on the feudal system. The financial structures that could promote industrialisation were not in place in rural society. In addition, the lack of political unity prevented the accumulation of sufficient capital for investment. Economic development did, however, benefit from the commercial activities of the port cities and the emergence of major banks in the towns.

Industrial growth therefore required the establishment of major financial structures and the development of modern banks. These new large banks were able to finance industry. Bankers therefore played an important role in companies. Many of them sat on company boards of directors. This gave them voting rights in the company. As the economy developed in this way, financial capital almost entirely controlled industrial capital.

The development of an internal market, stimulated by the internal free trade agreement, was the basis for industrial development and national unification. German cultural peculiarities also favoured economic development: strong commercial traditions already developed, financial traditions and corporatist organisation of labour.

Peasants, increasingly numerous in the countryside thanks to demographic growth, were increasingly moving to the cities where they sought work in the new industries. Companies were thus able to take advantage of an inexhaustible supply of unskilled labour. New urban agglomerations sprang up around coal mines and railway networks. Companies set up near natural resources and means of transport. Towns grew up around these companies. The large towns were mainly made up of a large number of factories surrounded by small houses for the workers.

Technical innovations also brought with them new industries, further away from the coal mines: metal processing, glassmaking, spinning and weaving.

As in all recently industrialised countries, working conditions were very difficult: long working days, exhausting tasks, unsanitary conditions. The same applied to living conditions, with housing that was too small, damp and poorly heated. What's more, the men, women and children all had to work. Conditions were just as difficult for the women and children as for the men.

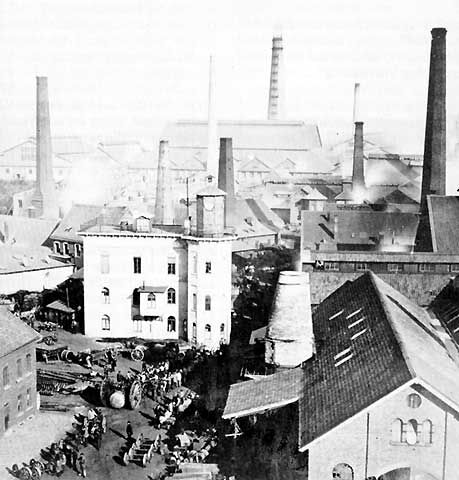

If the United States had its model of economic success with Rockefeller, Germany also had its model: the Krupp dynasty. The Krupp family's industrial adventure began in Essen in 1811. It was here that Friedrich Krupp founded his company dedicated to the production of molten steel. Krupp was inspired by techniques from Great Britain. However, he found it difficult to develop the right method and the steel he produced was of very poor quality. The company was in dire straits. In 1826, on the death of Friedrich Krupp, the company (then more or less profitable) was taken over by his widow and son. At the age of 14, Alfred Krupp was just learning about economics. Nevertheless, he managed to increase the profitability of his father's business. Development was fairly slow until 1850.

It was at this time that the boom in the railway industry greatly helped the Krupp company. Railways and locomotives required large quantities of steel. The Krupp company grew to become the largest steelworks in the world. Alfred Krupp benefited from the development of the railways, the navy and machinery.

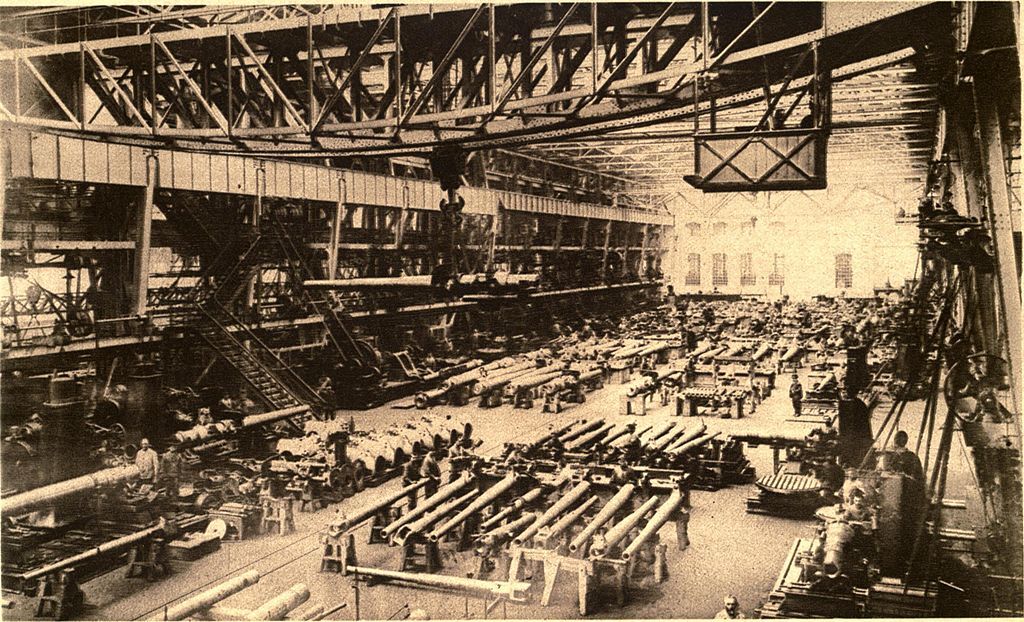

Alfred Krupp soon limited his production to axles and springs. In 1859, Krupp moved into military production, building cannons among other things. He also introduced new techniques to his factories. Always on the lookout for ways to increase his company's profitability, Alfred Krupp bought iron and coal mines. By 1887, the company had around 45,000 employees. When Alfred Krupp died, his son Friedrich Alfred Krupp took over.

Following in his father's footsteps, he bought a number of shipyards. The Krupp company benefited from its reputation and won many orders for military equipment. Krupp's development continued until the First World War, during which time it continued to grow richer. At that time, Krupp was a company renowned for its huge cannons. After the Second World War, the company concentrated on truck production. Today, the company is still in business. It merged with the Thyssen company in 1997, forming Thyssen Krupp AG, producing quality trucks.

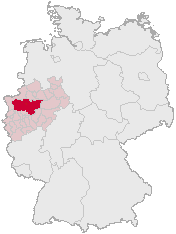

The Ruhr is a region of Germany located in North Rhine-Westphalia, in the west of the country. The region is bordered by the river of the same name to the south.

The region became urbanised during the industrial revolution in the 19th century, largely thanks to its mining resources. Coal mining led to the development of the metallurgical and steel industries. The construction of railways across the country boosted both industrial activity and the population of the region's towns. The Ruhr thus became Europe's most important industrial region.

The first popular movement directly caused by industrialisation occurred in 1844. As mechanisation became more and more established in production, artisanal production suffered from this competition. In fact, a number of businesses that had retained their traditional production methods went bankrupt.

Home-based craftsmen found themselves without jobs or income. These workers were soon affected by famine, and their living conditions became increasingly difficult, even miserable. This difficult situation led to a revolt among the craftsmen. However, this revolt was quickly crushed in bloodshed. The first workers' movement developed in Berlin. The Berlin revolution of 1848 was an opportunity for workers to demand respect for their fundamental freedoms. Like the craftsmen's revolt, the Berlin workers' revolt was a failure.

In 1875, the Workers' Party was founded in Germany. This party still exists today under the name of the Social Democratic Party of Germany. The party's mandate was to found a free state and a socialist society, to abolish exploitation and social inequality and to establish brotherhood for all. At the time, the party's aims also included the international community of workers.

In May 1875, the party adopted a political programme: the Gotha Programme. This programme set out a number of ideas and made a number of demands. In short, the Gotha programme considered that work was a source of wealth for the whole of society: everyone should participate in work and everyone should receive the fruits of this work according to reasonable needs. At the time this programme was written, society's problem was that the working class was dependent on the capitalist class, which controlled the means of labour.

Among the main demands of the Workers' Party were:

-

The establishment of state-run workers' companies;

-

A state under the diplomatic control of the working people;

-

Universal, secret and compulsory suffrage for all citizens aged 20 and over;

-

Direct legislation voted by the people; and

-

Military service for all and the formation of a standing army;

-

Restore freedom of thought and freedom of expression to the press;

-

General education of the people by the State, compulsory, free and secular;

-

Establish standards for a normal working day;

-

Prohibit work by children and women that is harmful to health and morals;

-

Protection of the life and health of workers.

This programme was heavily criticised by Karl Marx in Critique of the Gotha Programme.

.

Born into a family of Jewish shopkeepers in Poland, Rosa Luxembourg (1871-1919) allied herself early on with revolutionary socialist movements. Her involvement in the rebellion forced her into exile in Switzerland, where she continued her studies. She submitted a thesis on political economy. Her well-thought-out political ideas enabled her to carve out an important place for herself in the movements she joined.

Rosa Luxembourg moved to Germany in 1896, where she soon joined the ranks of the Social Democratic Party. She also became actively involved in the first Russian revolution in 1905, organising revolutionary propaganda. In 1907, she returned to Germany where she began teaching political economy and also founded the Socialist International Women.

She was arrested at the outbreak of the First World War for her activism and stance, and spent virtually the entire war in prison. At the end of the war, she founded the Spartakus League. It was from texts written in prison that the League's programme was drawn up. Never one to abandon her political and economic ideas, Rosa Luxembourg was always an active participant in social movements. In 1917, she welcomed the Russian Revolution, although she did not agree with Lenin's regime, which had abolished democracy.

When the German Communist Party was founded, it was she who drafted the political programme. Rosa Luxembourg's political career came to a swift halt in 1919, when she was murdered by officers.

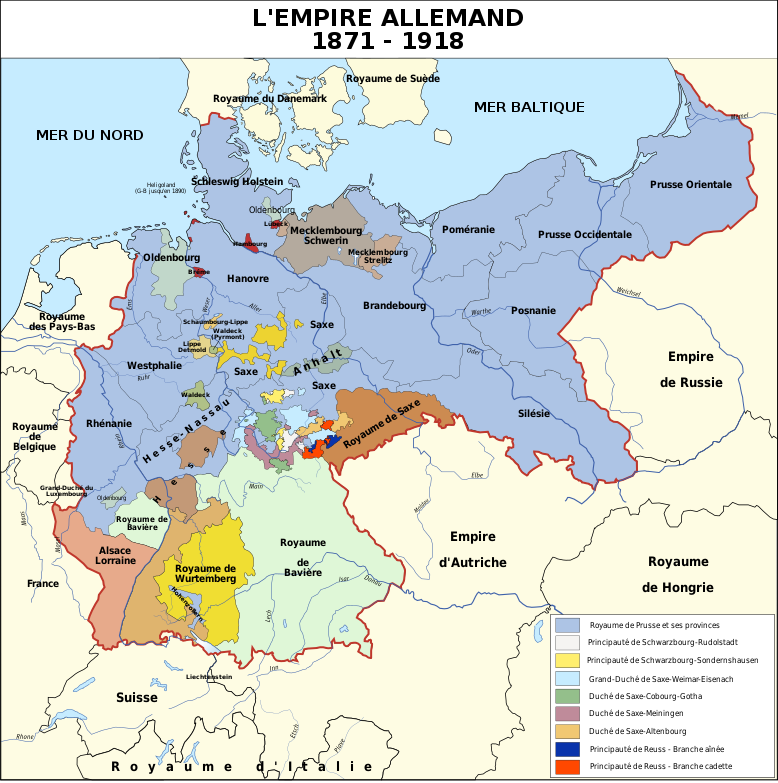

In 1870, when Germany's industrialization was booming, France was afraid of this new economic power. This is why Napoleon III opened a conflict with Germany. Unfortunately for him, the French army was wiped out by the German army. This victory enabled Germany to acquire Alsace and part of Lorraine. The end of this Franco-Prussian war was marked by the beginning of the German Empire, declared on 18 January 1871. With this declaration, Germany became the greatest power in Europe.

This new political formation was also known as the Second Reich (empire). The Second Reich was characterised by authoritarian and monarchical state administration. Political life also changed with the establishment of the Second Reich, as the state created two assemblies: an assembly of citizens (with virtually no real power) and an assembly of states (predominantly dominated by the Prussians).

Founded in 1915 by Rosa Luxembourg and members of the extreme left of the German Social Democratic Party, the Spartakus League quickly had a major influence on the workers. The workers were in disarray at the time, as the 1914-1918 war had put an end to the advances made by the Social Democratic Party. In fact, at the height of the war, the Social Democratic Party opposed workers' strikes.

This is why anti-war activists opposed to the new measures of the German Socialist Party came together in the Spartakus League, whose mandate was to organise the anti-war movement with the working class. Between 1917 and 1918, the Spartakus League instigated a number of revolts. In January 1918, several strikes took place in Germany: the workers demanded peace. On November 4 1918, in the port of Kiel, several sailors refused to obey an order.

Throughout the country, workers‘ and soldiers’ councils were formed. The aim was to give the working class a real political weapon. This is why the Communist Party of Germany was founded. This party grew rapidly, but was decimated just as quickly: the leaders were assassinated, and several important members were shot and executed. After that, the Communist Party never again found such strong leadership. The leaders vacillated between opportunism and left-wing measures..