Louis XIV was disappointed by New France’s demographic situation after being under the control of the companies. In 1663, there were only 3000 people in the colony. The King of France appointed Jean Talon as the first Intendant of New France and gave him the mandate to increase the population and diversify the colony’s economy.

One of Jean Talon’s first acts was to carry out a census of the colony in 1666. The data from this census would allow him to target New France’s demographic weaknesses. These were the main findings:

-

The population was too small.

-

There were not enough women and too many single men.

-

There was a lack of tradespeople: carpenters, tailors, artisans, etc.

Jean Talon used these findings to draft his settlement policies.

Before Jean Talon arrived, most of the immigrants who made the journey to New France were engagés. These were men with no qualifications who did not have enough money to pay for the crossing. They were therefore committed to work for the companies in the colony for a period of 3 years.

Jean Talon’s census highlighted a problem caused by the colony’s policy to recruit the engagés: it did not encourage people with different skills, such as cabinetmakers, blacksmiths, joiners, etc. to come to the colony. To solve this shortage of skilled workers in New France, Jean Talon reached an agreement with Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the Secretary of State for the Navy, to oblige merchants to hire tradespeople to make the crossing. This meant that the number of immigrants in the colony with a specific qualification gradually increased.

In 1665, the Carignan-Salières Regiment arrived in New France. Its experienced soldiers were brought to defend the colony against the threat from the Iroquoian nations. In 1667, after a peace accord was signed with the Iroquoians, the soldiers from the Carignan-Salières Regiment were free to return to France. The King took the opportunity to suggest that they establish a colony and to make the offer more appealing, he gave land to the soldiers and seigneuries to higher ranking officers. The plan worked and nearly 400 of them decided to stay.

To remedy the lack of women in the colony, Louis XIV sent the Filles du roi. They were orphans, mostly aged between 15 and 25, who were given free passage to New France to marry the men there. The aim was to increase the population by increasing the number of childbirths. From 1663 to 1673, nearly 800 young women arrived in New France to get married.

Jean Talon wanted to increase the number of children born in the colony and implemented several policies to encourage the habitants to get married and have children:

-

Cash bonuses were paid to families with 10 living children or more.

-

Fathers of unmarried sons over the age of 21 or unmarried daughters over the age of 17 had to pay fines.

-

Single men lost their trading, fishing or hunting license if they refused to marry.

-

The King gave money to men under 20 and girls under the age of 16 on their wedding day.

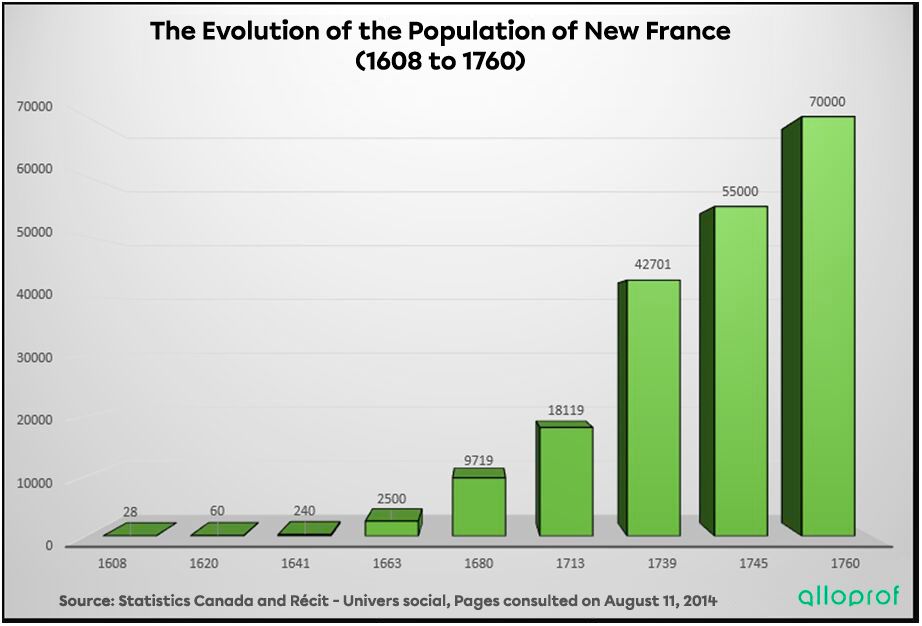

These policies quickly had positive effects on the population size, with the number of births increasing greatly over the following years. From Talon’s census in 1666 to 1713, the population rose from 3215 to 18 119.

The origin of the habitants of the colony was fairly homogenous—they mostly came from France and were Catholic. This was largely explained by the fact that people had to be Catholic in order to be allowed to immigrate into New France.

In the 18th century, most of the immigrants were from modest backgrounds, socially speaking: 80% of New France’s population were farmers. However a high society did exist, made up of nobles, the bourgeoisie, military officers, seigneurs and civil administrators.