With local trade well established, the stage was set for relations to be established between the towns, villages and markets of Europe. This is how trade fairs and large-scale commerce developed.

With the Crusades, Europe got a taste of luxury goods from the East (spices and silks) and Africa (gold and precious stones). Gradually, traders and travelling merchants spread these goods from southern to northern Europe.

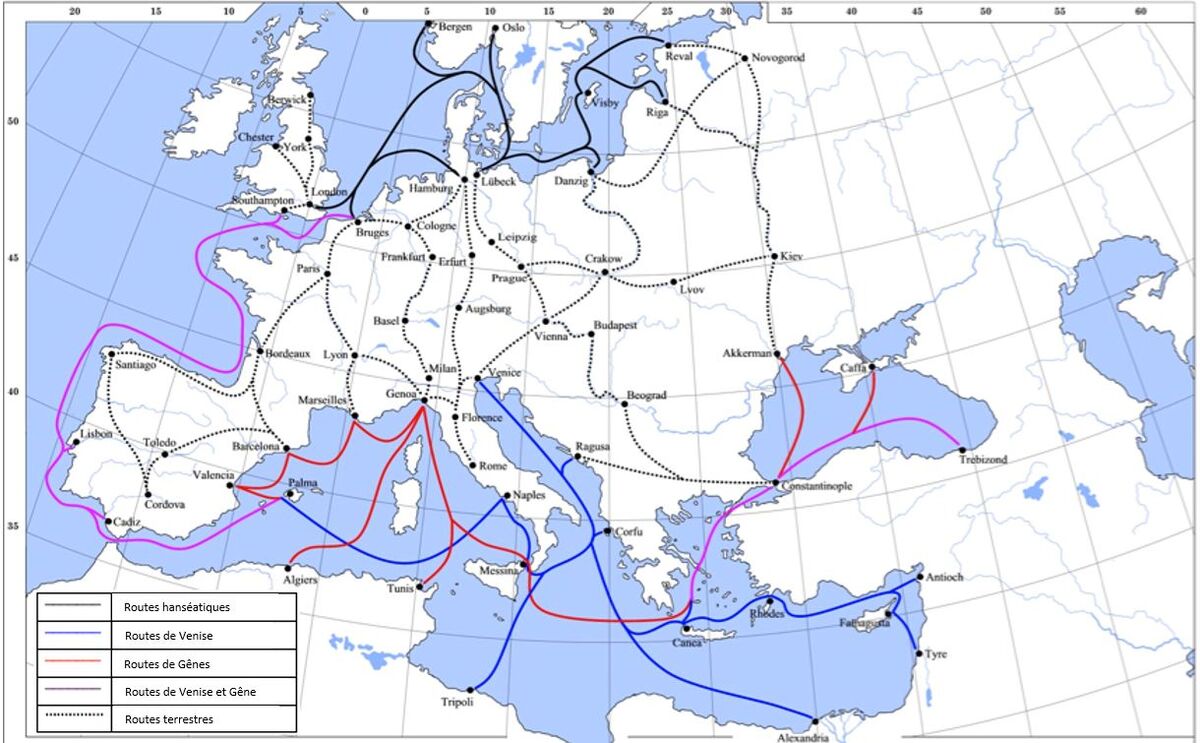

Two major routes were established:

- The first was around the Mediterranean via Venice and Genoa in Italy.

- The second was around the North Sea and the Baltic Sea, controlled by Cologne in France and Danzig in Eastern Europe.

The different sea and land routes

To transport these exotic goods, merchants used sea and land routes. Both types of transport underwent considerable improvements, enabling them to adapt to the growing trade.

- The rudder, compass and astrolabe made sea transport easier.

- Iron bands, harnesses, hoof nails and the use of horses improved overland transport.

However, travel on the European continent remained relatively difficult and time-consuming because of the mud and the lack of bridges, which slowed down the speed of travel.

A medieval trade fair

Unlike local markets, trade fairs or fairs are large gatherings of merchants who meet in different places at a fixed time each year. They can last for days or weeks on end, and people come from all over to trade goods from Europe, Africa or the East. Each region, kingdom and even town specialises in the production or manufacture of certain goods specific to its territory (drapery, metals, spices, etc.). This is why the cities and trade fairs involved in large-scale commerce complement each other.

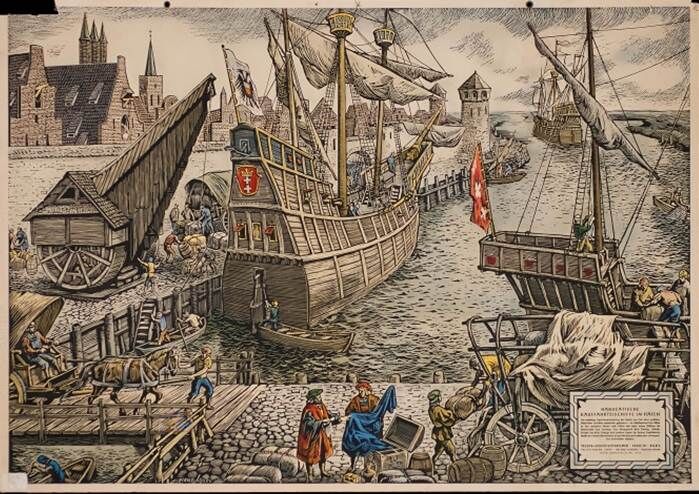

A group of traders, a guild, who arrive at their destination safely

With so many ships travelling by land and sea, cargo security was a major problem for the merchant bourgeoisie. Sea and land routes were overflowing with pirates and brigands who took advantage of the cargo's wealth. To ensure greater security when transporting goods, merchants formed guilds. By setting prices, these guilds accumulate wealth that can be used to secure their trade routes with armed caravans.

A guild is a group or association of merchants or traders engaged in the same activity (trading in this case). Each guild sets its own Papal edict and prices. In return, it asks for the protection of the towns or villages where it sets up for its trade fairs.

A Hanseatic League is a group of guilds and large merchants that establishes Papal edict, privileges and monopolies on certain products at European trade fairs or fairs, as well as ensuring the safety of goods transported by sea or land. A Hanseatic League is also known as a Hanseatic League.

The various guilds then grouped together into Hanseatic Leagues, which made it easier for them to impose their will on the city lords and secure a monopoly on products from Asia, Africa or even other European cities. The Hanseatic Leagues established themselves in European trade and enabled certain bourgeois to occupy increasingly influential positions in Western European society.

A money-changer and his wife

As trade grew, it became increasingly complex and difficult to manage. Certain professions, such as money-changers and bankers, became necessary to facilitate large-scale commerce.

Because the currency differed from one town to another or from one region to another, trade became more complex. A new type of profession emerged, that of money-changer. The money-changer became an important player, enabling merchants and traders to exchange money and bills of exchange from an outside town or village.

In the Middle Ages, a banker was a man with large sums of money that he lent in exchange for interest. Merchants, who were regular customers, borrowed money to buy goods or to pay for their transport. These merchants must repay the amount borrowed on a date fixed in advance, plus interest, or else incur higher penalties.

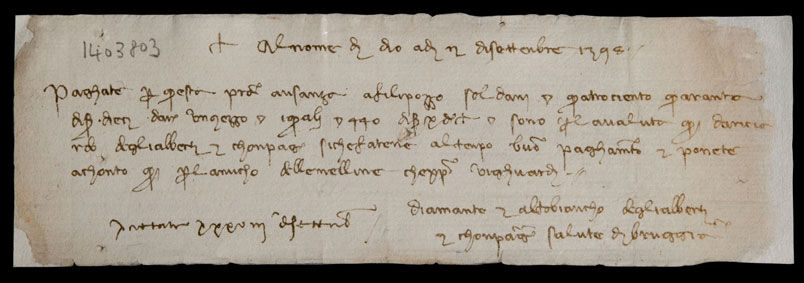

A bill of exchange is a document written by one person (the drawer or supplier) to another person (the drawee or customer) asking them to pay a specified amount of money to a third person (the beneficiary). A deadline must be respected (a fixed date that must not be exceeded). The bill of exchange is the forerunner of the cheque.

A bill of exchange dated 2 September 1398

A merchant from Venice wants to take 1,000 gold coins from Venice to the Champagne trade fairs. He is afraid of being robbed on the way by bandits, so he uses the services of a money-changer.

- The merchant visits the first money-changer in Venice and gives him his 1,000 gold coins in exchange for a bill of exchange of the same value.

- The merchant travels to Champagne with his bill of exchange, which only he can use.

- At the Champagne trade fair, he visits a second money-changer and gives him his bill of exchange. He receives the equivalent of 1,000 gold coins in various currencies, which he can use in Champagne.

The merchant has therefore made the journey between Venice and Champagne safely and can now use his money to trade at the fair.