The concepts covered in this fact sheet go beyond those seen in high school. It is intended as a supplement for those who are curious to learn more.

In the early Middle Ages, roads, pavements and bridges were still in good condition. The network of roads developed during the Roman Empire covered the entire European continent, even the most remote areas. The network was also dotted with horse relays and numerous inns. These infrastructures greatly facilitated travel and trade.

However, from the end of the Roman Empire onwards, rulers gradually abandoned the network, which deteriorated steadily for over two centuries. Despite increasing wear and tear, the roads remained in use until the 7th century. In the 8th century, at the time of Charlemagne, there was a commercial, intellectual and religious renaissance. Merchants and travelers once again used the roads.

After the fall of the Roman Empire, land routes were less practicable. Many merchants, particularly those from the Germanic Roman Empire, took to the sea instead. However, navigation was also limited by the high number of pirates and privateers. Shipping declined, as did shipbuilding.

The Venetians and Genoese took over shipbuilding. They fought fiercely for control of Mediterranean trade. By the 13th century , maritime trade was back on track, with the Italians even succeeding in linking their country with Flanders and England. The Portuguese, on the other hand, had better ships for crossing long distances. That's why they sailed all the way to Asia. Thanks to its monopoly of the spice trade, Portugal was the richest country in Europe on the eve of the Renaissance and the great explorations.

The rebirth of trade came to a swift end in the early 10th century, as feudal rule took hold. Unmaintained roads were not only less pleasant to travel, but also unsafe due to the presence of numerous outlaws. The High Middle Ages were therefore characterized by a retreat to the lord's lands. Few travelers or merchants used the roads. The seigneuries lived independently. Towns and cities were abandoned.

Under feudal rule, most goods were exchanged by barter, and there was no longer any metallic currency. For example, the city of Rome, which had no fewer than 500,000 inhabitants in the 1st century BC, had no more than 50,000 by the 10th century.

It wasn't until the second half of the 11th century that trade quietly resumed on European roads. Strongly linked to the urban boom of the 11th century, the revival of trade was also due to the maintenance and protection of numerous roads.

For example, more and more pilgrims were heading for Compostelle. The Chemin de Compostelle, also known as the French Way at the time, was maintained, protected and defended by knights. The route was gradually used by many travellers and itinerant merchants.

The urban boom, combined with a higher level of safety on the roads, encouraged the emergence of a new trade motivated by the quest for profit and facilitated by the return of metallic money. Several merchants' associations sprang up before taking control and monopolizing commercial activities.

Agricultural surpluses, better security in towns and improved transportation networks led to the rise of trade. The rise of trade and an increase in urban activities explain the diminishing influence of feudal castles. Lords became less wealthy, while merchants and bankers became more wealthy.

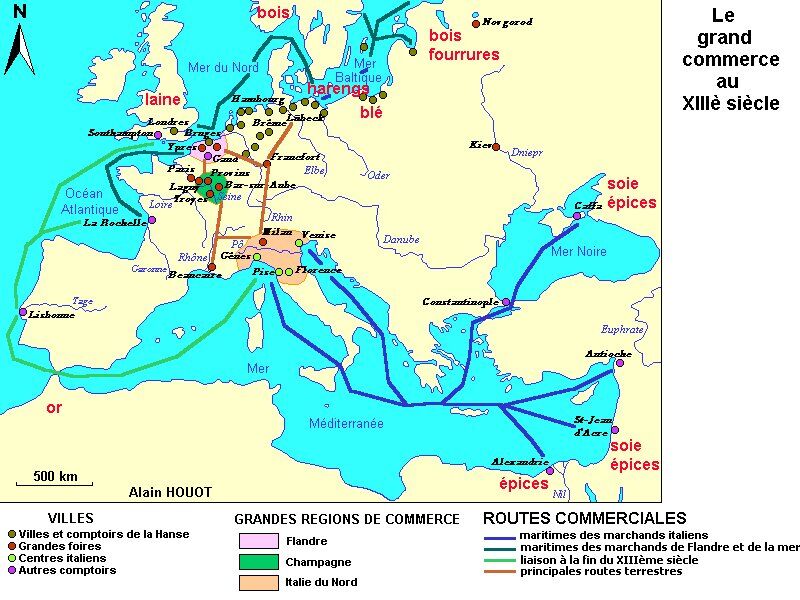

The Grand Commerce was based not only on trade between people in the same region, but also on trade with other countries, creating an established trading system between all the countries of Europe and Asia, the Arab Empire and the Byzantine Empire.

The great port cities took full advantage of their geographical position to control maritime routes and capture a share of international trade. Fleets and caravans benefited from the land and sea routes developed during the Crusades. These routes gave them access to the riches of India, China and the whole of Southeast Asia. Merchants obtained coveted goods from Eastern cities and Byzantium (Constantinople) , before selling them at fairs.

In northern Europe, port cities controlled all North Sea and Baltic Sea trade. In the south, Italian port cities controlled all Mediterranean trade.

Notes : An image in English is coming soon.

Without technological innovations, merchants would not have been able to transport so many goods. Grand Commerce was largely dependent on these advances.

For road transport, merchants benefited from inventions in the field of ironwork. The wheels of carts and wagons were encased in iron, making them stronger. In addition, new types of harnessing and hitching facilitated the transport of heavy loads. Roads were paved for faster, more efficient travel.

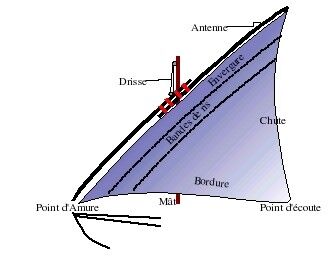

Maritime transport also underwent numerous innovations that enabled port cities to grow richer. Ships were built to be more durable and capable of longer voyages. Navigators also benefited from better navigation instruments: compass, sextant, astrolabe. In addition, certain features made ships easier to maneuver: triangular lateen sails (for windward and beam sailing), stern rudder, yard (for steering the square sails attached to the mast). Some ships even had a second mast.

Notes : An image in English is coming soon.

Not only did all these innovations enable the development of a vast commercial network, they also led to the great explorations of the Renaissance.

Capital is the totality of a person's or company's assets that can be used to generate income.

Capitalism is an economic and social system based on private ownership of the means of production. Great importance is attached to the pursuit of profit, and to those who own capital (money). Capitalism also encourages individual initiative and competition between companies.

Merchants established operating methods that enabled them to accumulate profits quickly. They bought large quantities of goods. They could even buy a whole load or a whole lot. They would then resell these goods at major fairs such as the Champagne fairs. For them, the purchase of merchandise represented an investment that they wanted to make profitable.

To make this sales system work, merchants sometimes needed financial assistance. That's why many moneychangers took part in fairs. These moneychangers had several functions, including lending large sums of money to merchants. The moneychangers profited from the interest on the money loaned to them to enrich themselves.

Another function of the moneychangers was to establish the value of coins. The use of metallic money was once again widespread, but was not standardized from one region to another. The value of a coin was determined by the quality and quantity of the metal of which it was made. Moneychangers were in demand, as coins soon became a necessity for all transactions. Money had replaced barter.

The aim of moneychangers and merchants was to accumulate as much capital as possible, hence the interest in seeking out goods from distant regions (Muslim Empire, Byzantine Empire, Asia) that were rich in coveted and expensive goods. Money-changers and merchants would then meet up in the great trading ports of Northern Europe or the Mediterranean. Goods were then distributed throughout the continent via fairs and markets. At the time, the wealthiest merchants were those who specialized in oriental goods: pepper, nuts, cinnamon, oil, etc.

Merchants often carried large sums of money with them, and didn't want to risk being robbed. This is why the use of bills of exchange spread. This letter guaranteed the merchant that he would receive the agreed sum if he presented it to a changer or banker. Bills of exchange were used by Italians as early as 1300, but really took off throughout the 14th century. They are in fact the ancestor of today's cheques.

The Italians had developed specific sales methods that slowly spread throughout the continent. These methods encouraged the development of the bourgeois class and international trade. Indeed, it was Italian merchants who first used techniques such as loans and bills of exchange. They gradually settled down, sending clerks out on the roads and seas while they stayed in town to better manage their business.

The main trading activities took place near the two main poles: in the north, near the Baltic Sea, and in the south, near the Mediterranean.

Note : An image in English is coming soon.

The Netherlands controlled trade on the North and Baltic seas. Northern products (fish, wine, salt, furs, metals, cloth) were traded there. The most important city was Bruges, a major producer of cloth. The great Russian rivers flowing into the Baltic Sea also favored trade and contacts with Asia.

The Baltic Sea was an important crossroads for trade, facilitating trade with the north of the continent, Scandinavia and England. The second major pole was in the Mediterranean, where the Italians, more specifically the Venetians and Genoese, had taken control of all sea routes thanks to their vast trading fleet.

Venice possessed a huge fleet whose ships always returned in time to take part in the major fairs held at Easter, September and Christmas. The Venetians had allied themselves with the Byzantines and the Crusaders, which gave them many commercial advantages (monopolies and routes to Asia).

Genoese merchants had the same ambitions as the Venetians. However, they did not have the same methods or the same efficiency. Even so, they were well situated enough to have a monopoly on alum, a necessary substance for the flourishing dye industry.

Gradually, new towns grew in importance as they developed their own specific commodities. The cities of Florence and Milan, for example, began to produce cloth, leather goods and weapons, giving them a greater stake in Italian trade.

With the strong associations of merchants and cities linked to trade, new centers also developed. This was the case of northern European towns whose alliance (Teutonic Hanseatic League) made them one of the richest points of the 13th century.

Note : An image in English is coming soon.

- From Russia and Prussia: furs and wax;

- From the Flemish: cloth;

- From the English: cloth and wool;

- From Scandinavia: dried and smoked fish, copper, iron;

- From France and the Rhine: wines.

It was to protect themselves against these increased risks that merchants began to create guilds. These established highly codified privileges and jurisdictions recognized by all merchants. Guilds set prices, controlled the weight and measure of goods, and had a monopoly on commercial activities. Guilds included both merchants and carriers.

Initially, hanses were groupings of guilds with higher ambitions, both in terms of trade and politics. Gradually, the hanses became leagues grouping together several merchant towns. These associations were extremely powerful. The London Hanse, for example, brought together some twenty towns in addition to London.

By 1230, the 17-town Hanse grouped merchants and clothmakers from all over the Netherlands and northern France. This association was so powerful that the states treated it in the same way as ambassadors from a large country. The power of most hanses came to an end in the 15th century.