During the first phase of industrialization, various industries developed near cities. These industries needed a large number of employees who did not necessarily have to be highly skilled. At the same time, farmland was becoming increasingly sparse, and many French Canadians living in the countryside were unemployed.

Some left the countryside to move to cities where they would have a better source of income. Through the second half of the 19th century, the population of the cities exploded, resulting in urbanization. Although the populations of cities increased, most people still lived in rural areas.

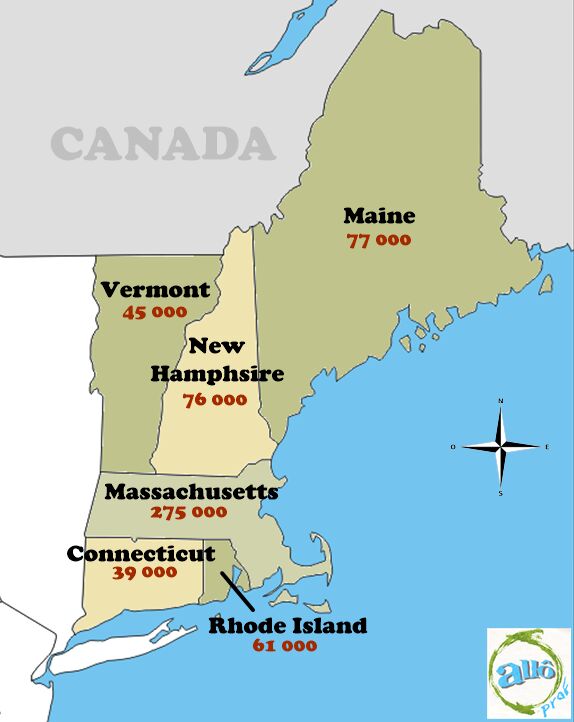

In the 1840s, several American cities near the Canadian border were growing at an impressive rate. The number of factories and jobs was on the rise, and workers could earn higher wages across the border than they could in Quebec. These factors convinced many French Canadians to head to the United States to seek employment and a better life. From 1850 to 1900, some 400 000 people emigrated to New England. This migration was so extreme it became known as “the great hemorrhage.”

There were so many French Canadian emigrants that districts were formed and these were known as “Little Canadas.” The Catholic Church even sent priests to open parishes for the French Canadians living in the United States.

Faced with this massive emigration, both the government of Quebec and the Church feared that the French and Catholic population would become a minority in a mostly Anglophone Canada. They decided to work together to prevent this outcome and keep Francophones in the region.

The Catholic Church also wanted to protect traditional values and believed that the population should stay in the countryside. This school of thought is known as “agriculturalism.”

Agriculturalism is an ideology that promotes rural living and a traditional way of life. It typically fosters traditional values (family, French language, Catholicism) and opposes industrialization.

The solution was to encourage agricultural colonization in new places, such as the Saguenay, Lac Saint-Jean, Laurentian, Témiscamingue and Ottawa regions. For this purpose, in 1888, the Department of Agriculture and Colonization was created. This department relied on Curé Antoine Labelle, who became involved in the development of new regions. The priest was particularly involved in colonizing the Laurentian region, or “Pays d’en Haut”.

By opening up these new lands and offering them to people, the government and clergy also hoped to reduce unemployment. The government built roads and railroads to reach these areas, but the harsh climate in these regions, combined with infertile soil, greatly limited the ability to cultivate the land. The areas were also far from the big cities, so farmers could not sell their surplus. By the late 1800s, barely 50 000 people had settled in these lands, compared to the 400 000 French Canadians who had left Canada to live in the United States during this same period. This colonization plan failed to achieve its intended objectives.

What’s more, the Indigenous nations were affected by this wave of colonization. Villages and farmland were often created on the territories of the Indigenous peoples, who were forced to move and find new hunting grounds or settle on reserves.

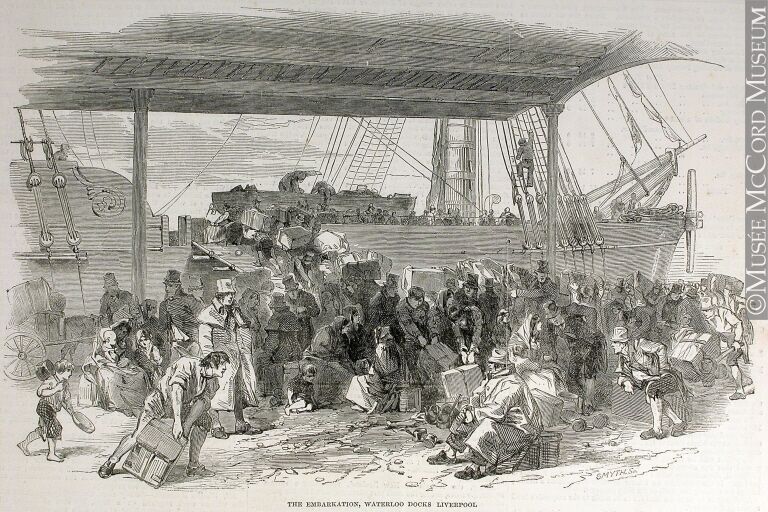

From the 1840s through the 1870s, more and more immigrants came from England, Scotland and especially Ireland, a country experiencing a famine caused by a crop-destroying parasite. Famine and poverty drove many Irish families to cross the ocean to America.

Migrants were crammed onto the ships, creating unhealthy living conditions. It was common for illnesses like typhus to develop aboard the ships, killing many people.

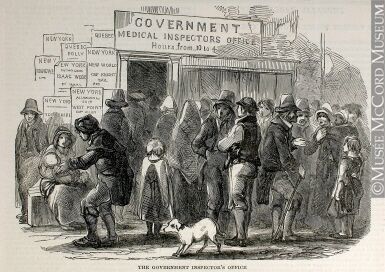

Immigrants from the United Kingdom settled in both the United States and Canada. Before arriving at the Port of Quebec and settling in Lower Canada, immigrants who were ill or who had symptoms of typhus or cholera were quarantined on Grosse-Île to keep them from spreading illnesses in the colony.

Being English-speaking Protestants, most newcomers settled in Upper Canada, but some 50 000 of them settled in Quebec City and Montreal, as well as the Eastern Townships.

Those who chose to live in Lower Canada were predominantly Irish, having the Catholic religion in common with the French Canadians. These Irish people were very poor and uneducated. Those who settled in cities mostly found work in factories. Otherwise, they worked in forestry, held jobs on maritime construction worksites and built canals.

In all, some 1.5 million immigrants settled in the Dominion of Canada during the second half of the 19th century. Despite this significant immigration, the population of Lower Canada fell due to emigration to the United States.