In the 1840s, the British government officially made the Church responsible for education, hospitals, asylums and charitable organizations, giving the Church power over several areas of public life.

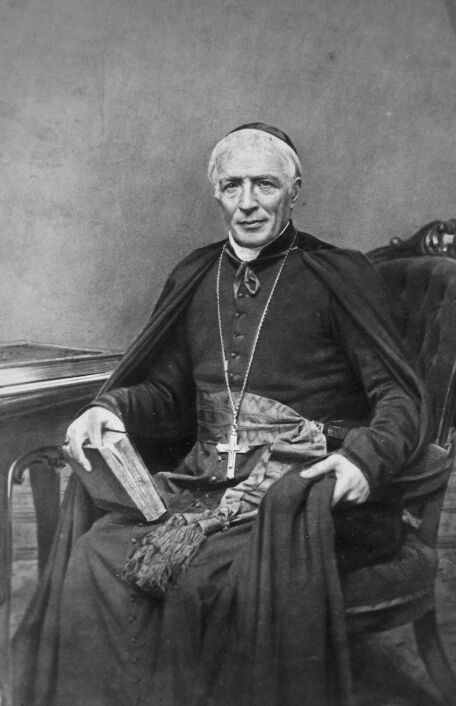

Monseigneur Ignace Bourget, the Bishop of Montreal, used various methods to increase the number of priests in United Canada. In Montreal, four religious communities were created and several others from France came to settle in the colony. Under Monseigneur Ignace Bourget’s mandate, many schools, hospitals and orphanages were built, and the number of members of religious communities in the Province of Canada went up significantly.

Two systems were implemented and developed alongside each other during this period. The various social institutions were separated into two, with Protestant Anglophones having their own schools and hospitals, while Catholic Francophones managed their own education and healthcare system.

The clergy gained importance because the Catholic Church collaborated with the British authorities. They had more people (priests, religious communities, etc.), responsibilities and power, and they began to wield a great deal of influence over French Canadians in 1840. In reaction to the growing influence of the Catholic Church, two opposing schools of thought emerged during these years: ultramontanism and anticlericalism.

In 1840, in United Canada, the Catholic Church was growing quickly and tried to increase its influence over the population.

Ultramontanism is an approach to politics that puts the Church at the top of the decision-making pyramid. In this type of system, the Church is the most important institution and should even have authority over the government.

Ultramontanists believed that only the Catholic Church could truly distinguish between good and evil, whether from a cultural, moral, religious or political point of view. Consequently, ultramontanists welcomed the School Act of 1841, which allowed the Church to share its values and to influence young French Canadians through their education. Catholic and Protestant schools started to co-exist in Lower Canada, from primary school through university.

Ultramontanists had very conservative values. For example, they opposed women being given the right to vote and they promoted living off the land and farming.

The values of the Church were at odds with liberal ideas. If writers and thinkers published works that challenged the Church, the faithful were prohibited from reading them. The philosophers of the Age of Enlightenment, such as Rousseau, were banned as they propagated ideas such as freedom of thought, freedom of religion and reason.

Liberals, who objected to ultramontanism, denounced the growing influence of the Church over the lives of Canadians, especially when it came to education. They wanted the government to be separate from religion. This is known as secularization, and it aims to keep institutions neutral.

Anticlericalism is a school of thought that seeks to give the Church control of religion only, but not politics or education.

The Institut canadien de Montréal was founded in 1844. This institute brought together both Protestants and Catholics who wanted to attend conferences on science, politics and philosophy. It also gave people a chance to read books and journals on different subjects such as law, science and literature. Some of these books were even part of the “Index,” a list of books that were banned by the Catholic Church. Several other such institutes were formed in Quebec City and Trois-Rivières.

The Institut canadien de Montréal disagreed with the growing influence the Church had over society. It defended liberal ideas that opposed the values of the Church, and for this reason, the Institute founded the newspaper L’Avenir to share its ideas. This situation did not sit well with the clergy or Monseigneur Bourget, the Bishop of Montreal, who actually ordered Catholics not to attend the Institute. He also threatened to excommunicate any Catholics who were members of the Institute.

An excommunicated person is somebody who is rejected by the Catholic community. It is the worst punishment that a Catholic can be given.

In reaction to the threats of Monseigneur Bourget and the excommunication of several members, the Canadian Institute closed its doors in the late 1870s. The Church successfully rid itself of its only real opposition, allowing it to maintain its influence in several spheres, including education, healthcare and politics.

In the early 1840s, French Canadians saw their identity being threatened by different provisions of the Act of Union and developed a new school of thought, called the nationalism of survival.

Nationalism is a school of thought that aims to promote or defend a nation. In this case, French-Canadian nationalism was at risk of dying out, which gave birth to the term “nationalism of survival.” The Catholic religion, the French language and culture were in peril.

In this context, the Catholic Church took on the role of representative of the French-Canadian nation and became the hub of the French-Canadian identity. The Church encouraged people to adopt a traditional way of life, namely farming, and also encouraged believers to have big families, with the father as the head of the household.