Maurice Duplessis was Premier from 1936 to 1939 and again from 1944 until his death in 1959. A lawyer by profession, Duplessis had close ties to the Catholic Church and sympathized with the traditional values it promoted, notably the back-to-the-land movement and the importance of large families. During this time, traditionalism and nationalism became popular in society.

As a devout Catholic, Duplessis gave the Church significant power in several sectors, including education and health care. The Church was a contributing factor in convincing the public to follow its government.

Source: Mgr Joseph Charbonneau [Photograph], (n.a.), circa 1940, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, (URL). Rights reserved*[1]

Duplessis thought that education and health care should remain the responsibility of the Church.

With the baby boom came the need for more social and healthcare services. Hospitals and schools were struggling to keep up with the number of births. The increase in church membership helped to meet the demand, but as funding was running out, the state allocated money to the Church to help it run its various institutions. However, in most cases, the amount of money allocated was insufficient and many schools only had a single classroom or poor heating.

Duplessis had very strong ties to the Catholic clergy and gave them significant powers, especially in the areas of education and health care. At the time, most schools were Catholic or Protestant and classes were taught by nuns and priests.

As demand increased in the sectors run by the Church, its influence in politics and society grew. Through education and health care, the Church kept its stronghold over the Québécois. The Church’s omnipresence in social and political affairs is called “clericalism.”

Clericalism is an ideology that supports the involvement of the clergy in political and public affairs.

In addition to being involved in various social sectors, the Catholic Church also had cultural influence with the support of the government. It would sometimes censor certain books and films that conveyed messages or values that went against the Church’s values

In Canada, some powers belong to the federal government, while others are given to the provinces. Duplessis placed great importance on provincial autonomy, which meant that he wanted Quebec to have as much power as possible. To maintain provincial autonomy, he refused federal aid for university funding in 1951. His speeches often revealed his fear that the Canadian government would try to take away the powers given to the province by the AANB.

On January 21, 1948, the Duplessis government adopted a national Quebec flag called the Fleurdelisé. The white cross represents the people’s Catholic faith and the fleur-de-lys represents the relationship between Quebec and France since Jacques Cartier was the first to introduce the fleur-de-lys to America. Once it was adopted, it replaced the British Union Jack that had previously flown over the Quebec Parliament.

Duplessis introduced provincial taxes in 1954 to enable Quebec to be more autonomous. With the Provincial Income Tax Act, the Quebec government collected taxes from personal income. Maurice Duplessis believed that these taxes would help the province manage its expenses better. As a result, Quebec residents began filing two tax returns each year.

To defend provincial autonomy, Duplessis promoted the French language, French-Canadian traditions, Catholicism and Quebec’s unique characteristics within Canada. Duplessis also proposed the Délégation générale du Québec en France, which gave Quebec the chance to represent itself in France independently of the federal government. In 1961, two years after Duplessis’ death, the Délégation générale du Québec à Paris opened its doors under Jean Lesage.

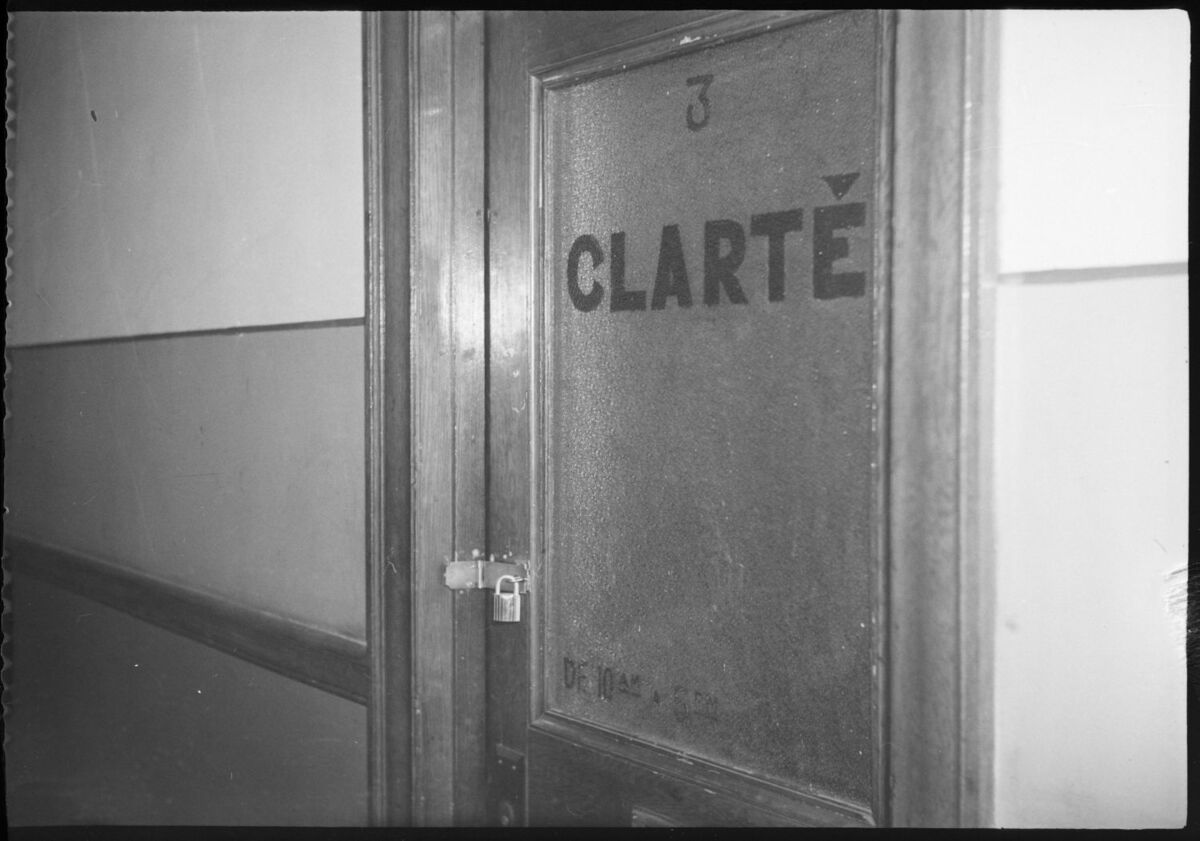

This censorship movement also led to the Padlock Act in 1937. Communism, an ideology opposed the liberal ideals promoted by Duplessis, was viewed as a threat. He therefore restricted access to certain areas that he thought might lead to a rise in communist movements in Quebec. The Padlock Act allowed the government to shut down establishments for one year, such as bars or trade unions suspected of being used to propagate or disseminate communist propaganda. The Padlock Act gave Duplessis the right to shut down the activities of his opponents and people who did not share his values.

The newspaper Clarté was closed down in 1937 under the Padlock Act.

Source: News. Door of Newspaper "La Clarte" closed by the Police [Photograph], Conrad Poirier, 1937, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, (URL).[2]

Maurice Duplessis' government strongly opposed unions. This opposition was particularly evident during labour disputes and strikes. The government always sided with employers and company owners. It passed laws that restricted or removed workers' right to strike.

However, these government actions did not prevent the rise of unionism across the province. Union movements became one of the major forces opposing the Duplessis government.

Working conditions gradually improved over the years.

The general strike by butchers in 1945 forced grocery stores and butcher shops across the city to close.

Source: Grève des bouchers de Montréal [Photograph], La Presse, 1945, Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec, (URL)[3].

Maurice Duplessis and his government were re-elected multiple times. However, various groups, like unions, and citizens challenged his decisions and methods.

Other groups contested clericalism. They disliked the significant presence and strong influence of the Church on the government and society in general. They denounced:

-

the censorship of books and films

-

the social conservatism of the Duplessis government and the Church

These groups were generally in favour of secularization. According to them, education and health should be managed by the state and not by the Church. They also believed that religious matters should belong to people's private lives and not within the government and its institutions. Furthermore, they called for a reform of the education system to catch up on the academic delays experienced by Francophone students.

A group of 15 artists, including Paul-Émile Borduas and Jean-Paul Riopelle, published the Refus global in 1948. This manifesto presented their vision for Quebec's future. Among other things, they denounced social conservatism and the Church's influence. They also advocated for the modernization of Quebec society.

-

(n.a.). (circa 1940). Mgr Joseph Charbonneau [Photograph]. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. (URL). *Content used by Alloprof in compliance with the Copyright Act in the context of fair use for educational purposes. [https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-42/page-9.html].

-

Conrad Poirier. (1937). News. Door of Newspaper "La Clarte" closed by the Police [Photograph]. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. (URL).

-

La Presse. (1945). Grève des bouchers de Montréal [Photograph]. Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. (URL).