In the late 19th century, the new Dominion of Canada sought to explore the west before colonizing it. After purchasing Rupert’s Land and the North-Western Territory from the Hudson’s Bay Company, the Canadian government could then administer these territories, but also became responsible for the people living on these lands, including Indigenous peoples.

Wilfred Laurier was greatly inspired by John A. Macdonald’s National Policy, which planned for the colonization of Western Canada. In 1872, his government adopted the Dominion Lands Act, making land available to future immigrants for cultivation.

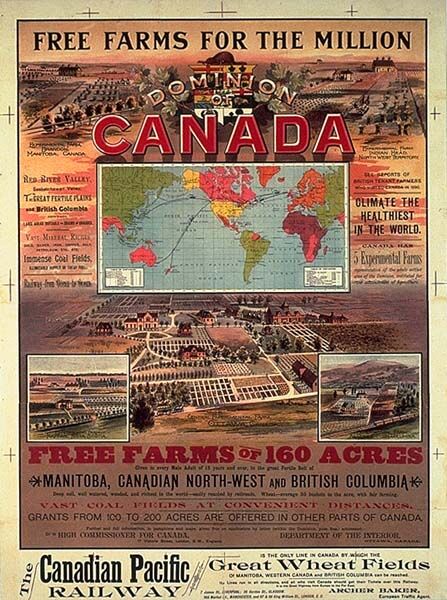

The federal government offered free land to attract immigrants to Canada.

The colonization of the West offered great economic potential. These lands would make it possible to increase wheat production, and the surplus could be sold to the USA and help establish a new market inside Canada.

The federal government built railroads to Western Canada to send immigrants to colonize these new lands.

In the late 19th century, the Indigenous peoples living in Western Canada were facing a number of serious problems, many of which were related to the huge influx of immigrants to their territory. Not only did they suffer from epidemics, but there were also periods of famine as the buffalo herds disappeared due to over-hunting of these animals by newcomers. These events caused Indigenous peoples to rebel against the arrival of immigrants on their ancestral lands.

In 1869, the Canadian government began colonizing by sending surveyors to assess the land around the Red River in what is now Southern Manitoba. The goal was to create lots for new immigrants. However, the colonization of Western Canada would not be without conflict.

John A. Macdonald, the Canadian Prime Minister from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 to 1891, organized the colonization of Western Canada.

The Métis people living on these coveted lands resented the arrival of the White colonists, fearing they would lose their culture and land rights. The Canadian surveyors were unwelcome among the Métis, who took up arms to block their progress. This would mark the first Métis uprising: the Red River Resistance.

The Métis were a people of mixed European and First Nations descent. They were marginalized and came together in communities in Western Canada away from the colonized lands. The Métis formed one of the three groups of Indigenous peoples of Canada with the First Nations and the Inuit. With roots in French-Canadian culture, they were mostly Francophone and Catholic.

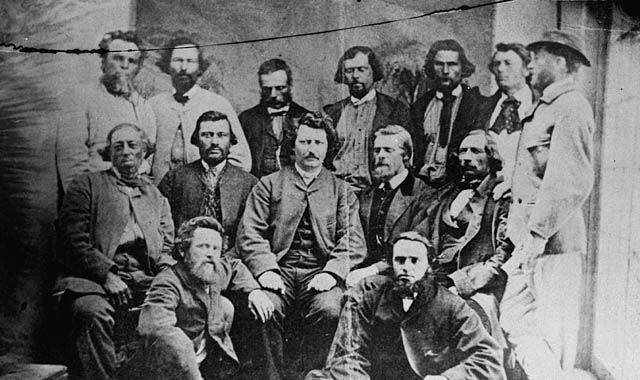

To counter the threat of Canadian colonization, the Métis established a provisional government that represented all of their communities. With Louis Riel leading them, this political group made a number of demands to ensure that the colonization of their lands would be done in a way that respected their territorial and cultural rights. In March 1870, Thomas Scott, a colonist from Ontario, was killed by the Métis. This act increased tensions between the groups. As the Métis leader, Louis Riel feared being sentenced and executed so he fled to the USA.

Louis Riel (centre) was in charge of the provisional government of the Métis.

The result of the negotiations between the Métis and the government was a new province: Manitoba, where the English Canadians and the Métis would live together. However, the rapidly growing Canadian population soon had the Métis outnumbered. With greater say in the political system of the province, the English Canadians gradually voted in laws to restrict the rights of the Métis.

Feeling that they were no longer respected nor welcome in Manitoba, many Métis left the province. They migrated to the north-west region of Batoche. However, Canadians continued to spread westward and gradually reached the new lands inhabited by the Métis. The Métis wanted to be heard and challenged the presence of colonists on their territory. Louis Riel returned from exile to defend the interests of the Métis. Now that the climate was even less hospitable than before, the Métis took up arms again in 1885. This uprising is known as the “North-West Resistance.”

Louis Riel organized a second rebellion by the Métis in 1886, this time in Batoche, in what is now Saskatchewan.

Faced with this situation, John A. Macdonald’s federal government decided to end the threat by sending the Canadian army to suppress the second rebellion. The construction of the railroad allowed the army to move much faster and in greater numbers than it did in the first rebellion. In 1885, Louis Riel and the other rebels were arrested and imprisoned. Louis Riel was accused of high treason against the nation and was hanged by the Canadian federal government.