The negotiations orchestrated by Pierre Elliott Trudeau around the patriation of the Canadian Constitution provided Indigenous nations an opportunity to advance their interests within the federation. After Canadian courts legitimized their requests, Indigenous peoples organized and asserted their specific status by demanding more independence from the federation. Public opinion slowly became more favourable to the claims of Indigenous peoples as the media covered the injustices they suffered. First Nations have worked to assert their rights in Quebec and Canada through legal battles, constitutional action and sometimes armed struggles.

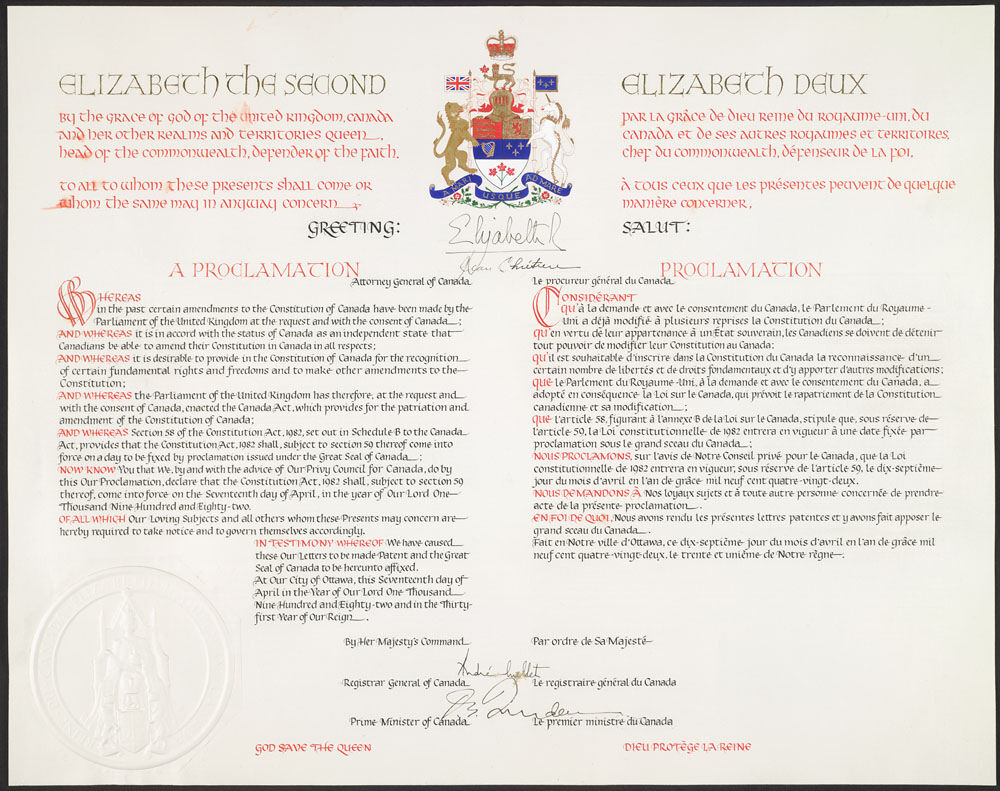

Pierre Elliott Trudeau prepared to patriate the Canadian Constitution without consulting First Nations. But after pressure from Indigenous peoples, he eventually added Article 35 recognizing Indigenous rights to his proposal. This article is essential for First Nations because it represents the constitutional recognition of hard-won Indigenous gains made by negotiating nearly 70 historic treaties, some of which were even signed during the period of New France. Article 35 also defines the Indigenous peoples of Canada as Indian, Inuit and Métis.

The Constitution Act of 1982 included Article 35, which recognizes the ancestral rights of Canada’s Indigenous peoples.

During 1985 and 1989, the government of Quebec also acknowledged the ancestral rights of the eleven nations on its land. This acknowledgement obligated the government to negotiate agreements respecting the rights and independence of Indigenous peoples.

A significant territorial dispute in Quebec marked the beginning of the 1990s. This crisis involved protesters from the Mohawk community of Kanesatake, Quebec police and the Canadian Army. Problems began when the Mayor of Oka approved a real estate project and golf course expansion. These projects encroached on disputed lands where a Mohawk cemetery was located.

The negotiations organized to resolve the conflict were complex. Faced with an impasse, a group of protesters called the Warriors decided to build a barricade and arm themselves in protest. When they blocked vehicle traffic on a major road in the Montreal suburbs, the police intervened in the protest. During the short gunfight that followed, a policeman lost his life.

The conflict then became very tense and the Canadian army intervened by sending in 2,500 soldiers. After 78 days of conflict, the crisis ended with the arrest of the Warriors and the government’s promise to conduct negotiations to recognize the territorial rights of the Mohawks. The crisis worsened relationships between Indigenous peoples and Québécois.

The Oka Crisis created a tense atmosphere between the Warriors and the Canadian army.

Shaney Komulainen, PC archives.

After the Oka Crisis, the federal government wanted to restore damaged relationships with Indigenous communities. As such, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples was established in 1991 to investigate the foundations of a fair and equitable relationship between Canadians and Indigenous peoples. That said, no recommendations from the commission’s report were in fact adopted.

A dispute arose between the Cree and the Quebec government in 1990 which was eventually brought before the courts. The dispute lay in the Quebec government’s desire to expand its hydroelectric dam network, which, according to the Cree, breached the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement signed in 1975.

However, after several years of negotiations, Bernard Landry signed the Peace of the Braves with the Cree people, represented by Ted Moses. Under this agreement, the Cree abandoned their lawsuit in exchange for $4.5 billion and the promise of economic development in the region’s Indigenous communities by including them in mining projects. The Peace of the Braves recognized the independence and ancestral rights of the Cree, marking a new chapter in the relations between this people and the government of Quebec.

In 2002, Ted Moses, James Bay Cree Council Grand Chief, and Bernard Landry, Quebec Premier at the time, signed the Peace of the Braves. This new agreement puts to rest a dispute that had persisted since 1990.

Bernard Landry, premier ministre du Québec et Ted Moses, Grand Chef du Grand Conseil des Cris de la Baie James [Photographie], (2002), Hydro-Québec, (URL). Rights reserved.

In 1999, a landmark agreement was ratified leading to a significant territorial change. The Nunavut Act prompted the creation of a territory with the same name after an agreement between the federal government, several Inuit communities and the Northwest Territories. Nunavut was recognized as one of the three Canadian territories under this act, establishing its own democratically elected government. The Indigenous peoples of Nunavut gained a great deal of independence through this Act.

Nunavut officially became the third Canadian territory in 1999.

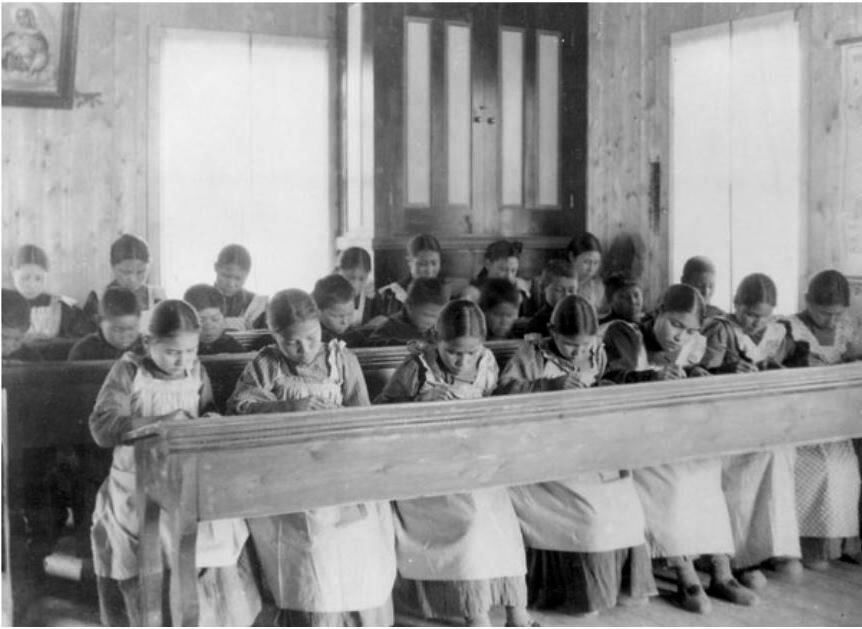

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada was established in 2008 to bring light to the injustices experienced by Indigenous peoples in residential schools. Through this project, the commission also aimed to lay the foundation for lasting reconciliation between Indigenous peoples and the federal government.