The concepts covered in this sheet go beyond those seen in secondary school. It is intended as a supplement for those who are curious to find out more.

The political, social and economic situation in France at the dawn of the French Revolution was influenced by two factors: the political organisation of recent centuries and the philosophy of Enlightenment. The political organisation of previous centuries was the main cause of the frustration experienced by many French citizens. For its part, the philosophy of Enlightenment represented the arrival of new values and new demands in the discourse of politicians and people interested in politics.

The Ancien Régime refers to all the years of monarchy or feudalism that preceded the French Revolution. The Ancien Régime is therefore a long period stretching from the Middle Ages to the 18th century.

At the end of the 18th century, the monarchy was challenged. After the absolute monarchy practised by Louis XIV in the 17th century, his successors were unable to manage France in the same way. Louis XV tried, but failed, at the very beginning of the 18th century.

A few years later, Louis XVI came to power. His reign was marked early on by riots and demonstrations of dissatisfaction. The commoners felt they were paying too much income tax and, because of the harsh winters, feared famine.

However, the state coffers were practically empty and Louis XVI decided to levy a new income tax, which aroused the discontent of the commoners. The situation continued to deteriorate as the king refused to share power with parliament. The elected representatives and the population asked the King to draw inspiration from the British parliamentary monarchy, which the King vehemently refused. Following this refusal, the King now had to react to the numerous riots that were raging. His advisers urged him to call an Estates General to quell the crisis. In the meantime, parliament suspended income taxes.

Before looking at all the events of the French Revolution, it is important to clarify certain concepts relating to politics and power.

Absolute Monarchy

In an absolute monarchy, the king rules alone in the name of the nation. According to the theory of divine right, he is God's representative on earth and all his subjects are like his children. However, the king is required to respect the laws and privileges of his subjects.

Constitutional Monarchy

In a constitutional monarchy, the king's power is somewhat more limited, as he must abide by the Constitution.

Constitution

A constitution is a document that brings together all the laws of a State concerning the various powers and their jurisdictions: legislative power, executive power and judicial power. A constitution also sets out the principles that govern the various institutions and the rights and freedoms of individuals. A constitution is therefore more restrictive than a set of laws.

Parliamentary Monarchy

A parliamentary monarchy operates in much the same way as a constitutional monarchy: the king's power must respect the provisions of the constitution. In addition, in a parliamentary monarchy, the government and the king are accountable to a parliament made up of elected members.

Republic

A republic is a political system in which the state must serve the commune. This is in contrast to all types of monarchy, in which the state may serve mainly private interests. In a republic, it is the commoners who decide and are sovereign. The commoners have the power to elect a government. This government then has power for a predetermined period only. A republic is not necessarily democratic because the government may deny certain social groups the right to vote or stand for election.

National Assembly

A national assembly is made up of all the people elected by the commoners. Generally speaking, the National Assembly has three main roles: passing laws, overseeing government action and amending the Constitution.

Constituent National Assembly

Constituent national assemblies function in exactly the same way as a national assembly, except that their roles and functions are based on the Constitution.

Legislative Assembly

A legislative assembly is one that is responsible for drafting and passing laws.

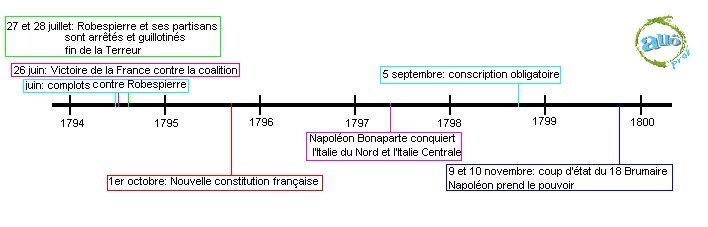

The Three Social Orders

The three social orders represent society as a whole. This division originated in the 11th century. At that time, the monks separated the population into three main groups: the clergy, the nobles and the Third Estate.

The clergy represents all men connected with the Catholic Church, while the nobility represents all those who exercise God's power on earth. The nobility therefore included royalty and their families, men-at-arms and all the powerful rich.

The Third Estate

The Third Estate is made up of the vast majority of French people. It is a very heterogeneous group that brings together several categories of people with different powers and social ranks. The Third Estate includes the bourgeoisie (some richer than others), shopkeepers, artisans, workers and peasants. Peasants accounted for around 20 million people at a time when the French population was around 24 million.

Under the Ancien Régime, the Third Estate bore virtually all the income taxes levied, in addition to the tithe payable to the Church, the forced labour performed for the lord, the cens payable to the lord or seigneurs, and so on. The Third Estate as a whole complained that they paid far too much compared with other groups. The bourgeoisie also complained that they were excluded from affairs of state, that they did not have access to the same tasks and responsibilities, and that they were not fairly represented.

Before the Estates General was held in 1789, members of the Third Estate were calling for equal income taxes, the abolition of feudal rights, the abolition of dues to pay and the creation of a constitution that would guarantee respect for rights and freedoms.

The Estates General

The Estates General are meetings called by the King. These meetings brought together all the elected representatives of the three social orders: the clergy, the nobility and the Third Estate. It was with the agreement of the Estates General that the King could take decisions on income tax and other aspects of policy. When Louis XVI convened the Estates General in 1789, it had not been convened since 1614.

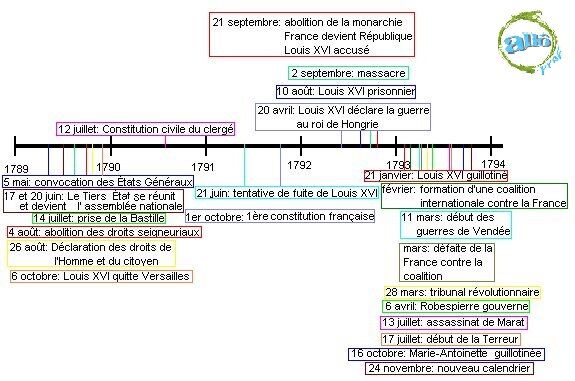

A number of significant events have changed political and social life in France. The French Revolution left many traces that are still present in French society today.

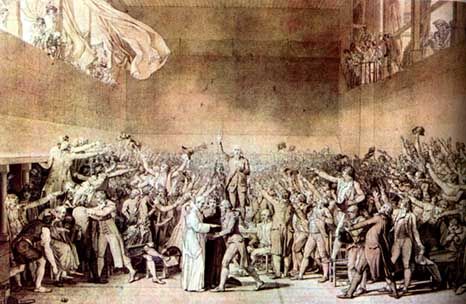

After much tension between the king and the commoners, Louis XVI followed the advice he had been given and convened the Estates General on May 5, 1789. The state coffers were empty, and the king wanted to create new income taxes to replenish them. He therefore called a meeting of all the elected representatives of the three social orders to Versailles.

Louis XVI quickly lost control of the meetings, while the bourgeoisie dominated the other groups in the Assembly. All the representatives of the Third Estate took the opportunity to denounce their minority status in the Estates General. Despite the presence of the Third Estate, it had no impact on the group compared to the nobles and the clergy, even though the latter two groups represented only a tiny proportion of the population.

On June 17, the elected representatives of the Third Estate and some members of the clergy met alone. Since they represented 96% of the population, they decided to form the first National Assembly. This new assembly met again against the King's wishes a few days later. The King had sent a messenger to warn the Assembly that it was acting against his orders. Mirabeau, one of the most active militants of the Revolution, harshly dismissed the messenger and the Assembly continued to meet.

It was this National Assembly that set about drafting the first constitution to define new Papal edict. The model for this constitution was The American Declaration of Independence. Once the constitution had been drafted, the Assembly became a constituent National Assembly.

During the Estates General, which did not go as Louis XVI had planned, the people of Paris heard rumours about the state of affairs and the King's reaction. Parisians were worried.

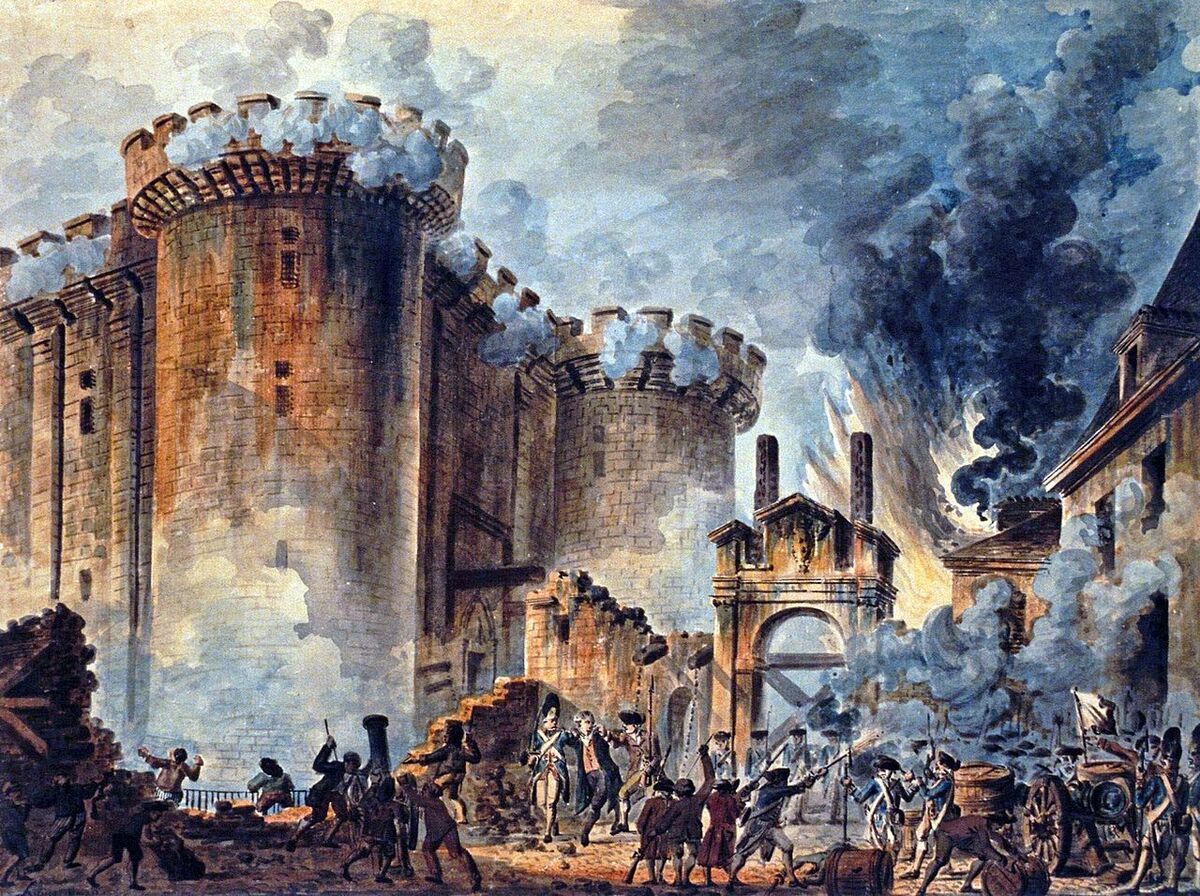

More and more people began to gather together, and the collective anger grew. On July 14, 1789, the population regrouped and suddenly stormed the Bastille. The Bastille was a fortress in the heart of the capital dating back to the Hundred Years' War.

It was during this assault that the first deaths of the Revolution occurred: some besiegers, invalids guarding the fortress and the governor of the Bastille. In a short space of time, the entire building was demolished. This event marked the real beginning of the French Revolution, a moment when the commoners participated massively in the movement of revolt and dissatisfaction. The Revolution left the confines of politics. After the Storming of the Bastille, some nobles began to flee France, including members of the King's family.

It is in memory of this popular uprising (the Storming of the Bastille) that France celebrates its bank holidays on July 14.

A new administration was set up in Paris. The population appointed a mayor and a commander of the national guard. The other cities of France soon followed the capital's example and set up their own town halls, whose power was independent of that of the king.

Although the revolutionary movement spread throughout the towns, the situation was very different in the countryside. The peasants, still loyal to the king, feared the fury of the lords. Several clashes took place in the French countryside. Peasants burned documents containing seigneurial rights. Some minor lords were even beaten or killed.

Faced with these increasingly violent acts, the deputies voted to abolish seigneurial rights on August 4,1789. Shortly afterwards, however, the King opposed this abolition, which only served to increase the population's anger.

At the same time, MPs drafted and voted in favour of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen on August 26, 1789. This declaration, inspired by the American Declaration of Independence, proclaimed that all men are born free and equal in rights.

Following the King's refusal to ban seigneurial rights, the population was outraged. On October 5, a crowd of angry Parisians set off to find the King at Versailles. It was Commandant La Fayette who managed to persuade the King to leave the Château de Versailles. He advised him to move to the Tuileries Palace in the centre of Paris instead. By living in the heart of the capital, the king could perhaps better dispel the people's mistrust of him. On October 6, the king left Versailles and moved to the Tuileries Palace. The Constituent Assembly followed him. The government of France was thus at the mercy of the people of Paris.

After such disturbing events, the whole population took a sudden and strong interest in political affairs. Numerous newspapers were created to inform the population of the latest events and also to spread revolutionary and counter-revolutionary ideas. In addition, a number of political clubs were formed, including the Jacobin Club, which would play an important role in the events of the following years.

It was in 1790 that the Constituent Assembly made a number of changes to the way the country operated: it drafted a constitution, created administrative departments (which are still in operation today), introduced a new unit of measurement (the metre) and introduced civil status (with civil marriages and divorces). However, the State coffers were still empty. The deputies therefore proposed seizing all the property and land belonging to the Catholic Church for the good of the State. Many people opposed the proposal, but the Assembly went ahead. In return, the Assembly also voted in favour of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which guaranteed an income for every priest.

It was in 1791 that the Pope sent his response to the Constitution of the Clergy, which turned out to be negative. Louis XVI, wanting to avoid a conflict with the Pope and the Church, withdrew from the Revolution at this point and went so far as to use his right of veto to stop the Assembly in its tracks. During the course of the year, the King tried to flee and rejoin those loyal to him, but was caught.

On October 1, 1791 it is the inauguration of the constitutional monarchy: the very first French Constitution had just been approved. The government also acquired a Legislative Assembly, which would henceforth have the power to create and sign new laws.

With this new Constitution, Louis XVI was no longer King of France with divine power, but King of the French. He now had executive power: the power to enforce the laws passed by the Legislative Assembly. However, he still had the right of veto, with which he could stop a law even if it had been accepted by the Assembly.

However, the new Constitution did not meet with unanimous approval among the population, and there were many tensions between each group. Tension increased between the king and the Legislative Assembly and between the Legislative Assembly and the clergy. Elsewhere in Paris, the members of the Constituent Assembly were not part of the Legislative Assembly, as they had not been allowed to register for the elections.

Frustrated by this situation, the members of the Constituent Assembly kept up the popular agitation in the political clubs. The anger of the commoners or the people continued to grow. This anger came to a head on August 10, 1792 when the crowd invaded the Tuileries Palace. The king and his family were taken prisoner.

It was the dismal failure of the constitutional monarchy and the Legislative Assembly. This failure ended in a bloody massacre on September 2. The government soon had to form a new legislative assembly: the Convention. This time, its members were elected by universal suffrage (only men could vote, as women did not have the right to vote). The new Assembly met for the first time on September 20 and, on September 21, proclaimed the abolition of the monarchy. 1792 thus became Year 1 of the Republic.

The Assembly also impeached the King as a traitor to the Revolution. Following this impeachment, two opposing factions formed in the Assembly: the Girondins and the Montagnards. The Girondins wanted to maintain the decentralised institutions as they had been since 1789. The Montagnards, on the other hand, wanted to establish a dictatorship. This dictatorship would be able to save the gains of the Revolution and hunt foreign armies.

It should be pointed out that the foreign kings had all been keeping an eye on French politics since 1789. From 1792 onwards, all the foreign kingdoms feared that the revolution would spread to their territories too. Over the next few years, France had to deal with both domestic political problems and foreign threats. In the summer of 1792, France was invaded by an army that included troops from Prussia and Austria. The French army rallied around a new anthem, La Marseillaise, and succeeded in driving the foreign armies back from the French borders. Today, La Marseillaise is still France's national anthem.

After accusing the king, the Montagnards obtained his death sentence. On January 21, 1793, Louis XVI was guillotined in the public square. However, the country still had to contend with increasing threats from foreign countries. They wanted to curb revolutionary movements, and this desire was even stronger now that the king had been put to death.

To better defend the country, the government decided to increase the strength of the army by 300,000 men. However, this decision undermined the country's internal stability and sparked off a major peasant revolt. This revolt turned into a civil war: the Vendée War. This was the most serious civil war in the history of France. It caused almost 500,000 deaths.

To calm all the confrontations, the government set up a revolutionary court before handing over power to Maximilien de Robespierre. He established a dictatorship. Calm was still far from returning to the country. The following months were marked by wars against foreign countries, internal wars against groups that did not support the dictatorship, the arrest of the Girondins and the assassination of Marat.

On September 17, 1793, Robespierre introduced the Law of Suspects, which allowed people to be arrested, tried and guillotined without the possibility of defending themselves. This law marked the beginning of the Terror: Robespierre sent thousands of people to the guillotine. In fact, during the 10 months of the Terror, it is estimated that nearly 20,000 people were killed, all of them accused without a fair trial. It was during this reign of terror that Robespierre promoted de-Christianisation by putting to death priests and all those who refused to join the Church. He also put Marie-Antoinette (the widow of Louis XVI) to death.

Robespierre also introduced a new calendar. In subsequent years, the dates were expressed in two ways, as those from Robespierre's calendar were given. Meanwhile, abroad, several countries formed a coalition against France: England, Austria, Prussia, Spain and others. The French were defeated in March by this coalition, which weakened the country.

The following year began with a weak economic performance. Trade with foreign countries fell steadily, which did nothing to help the economy regain its strength. In June, the deputies joined forces against Robespierre and his cronies. On 9 Thermidor (July 27), Robespierre and his allies were arrested. They were all guillotined the following day. The survivors who adhered to Robespierre's vision were nicknamed the Thermidoriens and put an end to the Terror. At the same time, a fight against the coalition was organised. At the end of June 1794, the French prevailed over the foreign countries. This victory vindicated the Revolution while at the same time devaluing the Terror and the dictatorship.

The end of the Terror and the death of Robespierre led to an increase in demands. The royalists dreamed of restoring the monarchy, while the remaining Jacobins still hoped to regain power. The National Assembly therefore had to put down the riots that emerged among these two groups. In addition, the Assembly was preparing a new constitution. This would establish a new regime: the Directoire.

A new change to the organisation of government divided the legislative power into two councils. In addition, the executive power (which had belonged to the king just a few years earlier) was now held by a five-person Directoire. The government began drafting a civil code, introduced a new currency (the Franc) and undertook a complete overhaul of education. It was at this time that the great engineering schools were founded. The end of the wars abroad and the greater stability of political life led to a strong upturn in the economy. The bourgeoisie also proudly flaunted their newfound wealth. Generally speaking, these bourgeois acquired their new wealth during the revolution by taking advantage of the treasures seized from the Church, the nobility and royalty.

Despite the economic recovery, the State's coffers are harder to replenish. Income taxes were proving insufficient. One proposal emerged from the debates: ransom and make a profit from conquered countries. It was at this time that a young general made his name. It was Napoleon Bonaparte who proved to be the man best able to make a profit from the conquered countries. He conquered northern and central Italy and imposed peace on Austria.

The Directoire wanted to ensure that the achievements of the Revolution were preserved. This is why it created sister republics, which would operate in a similar way to France. These sister republics were formed in Italy and Switzerland. However, the British threat still loomed over Belgium. This threat grew ever stronger and France found itself threatened on all sides. At home, the Directoire had to calm the threats from royalists who wanted to return to a monarchy. Faced with all these threatening forces, the Directoire made conscription compulsory in September.

The population expressed a number of dissatisfactions. The Directoire was prepared to make a number of compromises, except that of returning to the monarchy. At the same time, groups of conspirators were planning to overthrow the government, but in order to do so, they had to call on someone who was capable of doing so. They called on General Bonaparte. Thanks to a coup d'état on November 9 and 10 (18 and 19 Brumaire according to the revolutionary calendar), Napoleon Bonaparte succeeded in overthrowing the Directoire. He took power and established a new regime: the Consulate. Napoleon was to manage this Consulate with dictatorial power.

This event is considered to mark the end of the French Revolution. However, it did not mark the end of years of upheaval for France: 15 years of war under Napoleon, a return to the monarchy and the establishment of the Republic.

Several individuals were involved in the French Revolution: Louis XVI, Necker, the Marquis de La Fayette, Mirabeau, Robespierre, Marat, Danton, Saint-Just and Napoléon Bonaparte.

Louis XVI was born in Versailles in 1754. In 1770, he married Marie-Antoinette. He became King of France in 1774. During the first years of his reign, he continued his education.

Very early on, his reign was disrupted by the dissatisfaction of his commoners. In 1775, he had to react to the riots in Paris and, in 1783, the commoners rose up because they feared famine. When the king wanted to raise income taxes in 1787, the people were even less satisfied. It was against this backdrop that he convened the Estates General. Although he initially stated that he did not agree to share power, in 1789 he undertook to respect the Constitution.

After his attempted escape, the commoners and the revolutionaries considered him a traitor. At his trial, he was found guilty of conspiring against public liberty and the general security of the State, after which he was put to death.

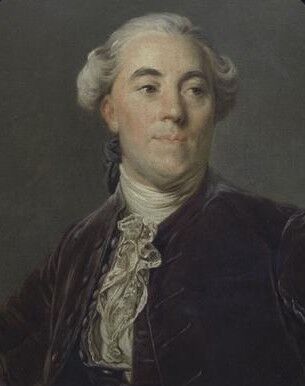

Necker was a financier who had long been involved in politics. Very early in his career, he thought it necessary to control trade in order to protect the poor. He resumed his career in finance and subsequently became Director General of the Royal Treasury and, later, Director General of Finance. Hired by Louis XVI, it was he who convinced the King to convene the Estates General and grant the Third Estate an equal number of deputies.

Just before the Storming of the Bastille, he was dismissed. He was later recalled and, this time, he strongly opposed the confiscation of Church property. After this, he resigned and ended his life in Switzerland. During his last years, he wrote several works in which he defended and justified his administration and his ideas.

Early in his youth, La Fayette joined the army, where he began a brilliant career before being appointed captain. He spent a few years in America, where he witnessed The American Declaration of Independence. He even became one of Washington's closest friends. In 1779, he returned to France. He was elected deputy and took part in the Estates General.

The day after the Storming of the Bastille, he was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the National Guard. He also invented the tricolour cockade, which was to become the symbol of the Revolution.

His actions after the start of the Revolution were not particularly noteworthy. However, his popularity plummeted when he shot at the commoners during a protest. He subsequently took part in the war against Austria, during which he was taken prisoner. During the years when Napoleon was in power, La Fayette was not very active. However, his political activities resumed when he took part in the overthrow of the Empire and was active in conspiracies during the Restoration.

After a brief trip to the United States, he was offered the presidency of the Republic. He refused and helped Louis Philippe First to take the post. He was again appointed commander of the National Guard during the bourgeoisie revolution of 1830. He was then forced to resign by Louis Philippe First, after which he left political life. He retired to his home and died in 1834.

The Comte de Mirabeau took part in the Estates General of 1789 as a representative of the Third Estate. From the start of his political career, he was immediately recognised as a great orator. During the Estates General, he helped transform the Third Estate into the National Assembly and was a staunch defender of the rights and freedoms of the press. He also took part in drafting the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen and was behind the creation of the départements in France.

He favoured a constitutional monarchy, a principle he tried to reconcile with the ideas of the Revolution. On January 30, 1791, he was elected President of the National Assembly, but died of natural causes on April 2 of the same year.

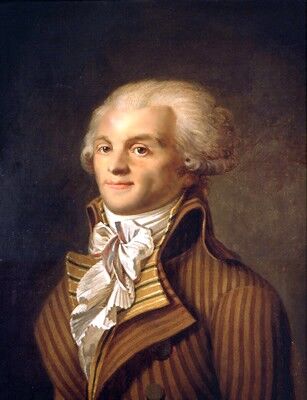

Maximilien de Robespierre came from the petty bourgeoisie and was trained as a lawyer. Despite his bourgeois origins, he was elected to represent the Third Estate at the Estates General of 1789. During the Revolution, he quickly made his ideas known: he was in favour of universal suffrage, the deposition of Louis XVI, a civic religion, and so on. He became the leader of the Montagnards and, once in power, introduced the law that marked the beginning of the Terror. This law removed any possibility for the accused to defend themselves.

Universal suffrage grants the right to vote to all citizens who are eligible to vote, i.e. under certain minimum conditions of age, nationality, etc.

Robespierre's power was strongly contested: several plots were organised and several deputies discredited his role. The Assembly even called for and voted in favour of Robespierre's indictment. He was arrested, but the people of Paris were waiting for a sign from him to start a riot, a sign that was slow in coming, giving the deputies enough time to take control, arrest those who supported Robespierre and find Robespierre himself signing a call for insurrection. Robespierre was tried without questioning or defence. He was guillotined on July 28, 1794. In the days that followed, 80 other supporters of Robespierre were also guillotined.

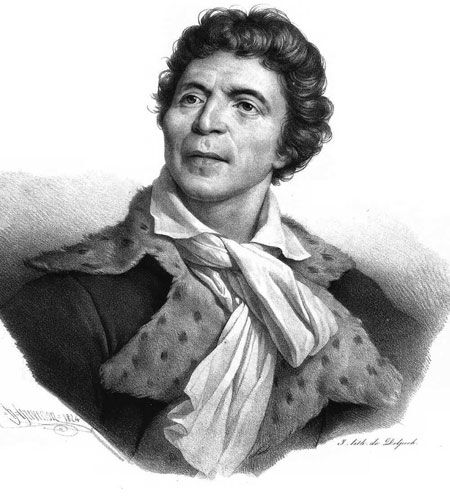

Jean-Paul Marat was born into a modest family. In 1774, he made a name for himself with a virulent pamphlet denouncing slavery and the attitude of princes towards the commoners. He subsequently tried to gain recognition from the Académie des Sciences for a number of scientific writings. The Academy's refusal only served to amplify his extremist ideas.

During the Estates General of 1789, he worked as a journalist. He conveyed his political ideas through his newspaper, L'Ami du peuple. His ideas attacked the aristocrats and the wealthy members of the Third Estate, who knew how to take advantage of every situation. After the Storming of the Bastille, Marat asserted that, to make a real break with the past, at least 500 heads would have to be chopped off. Marat hoped for a supreme dictatorship, which is why he joined forces with the Montagnards.

He did not live to see the victory of the Montagnards, as he was assassinated by a young royalist on July 13, 1793. His funeral ceremony was grandiose and all the revolutionaries paid tribute to him. Marat was so highly regarded that a painter paid tribute to him by depicting his assassination.

Georges-Jacques Danton came from a petty bourgeoisie and studied law. He did not take part in the Estates General, but encouraged his county to take up arms in 1789. He quickly gained popularity in political circles, as he was an excellent orator. In 1791, he was elected procurator of the Paris Commune and supported the Parisian Revolution. He was subsequently appointed Minister of Justice in the Provisional Executive Council.

In 1792, he was elected deputy for Paris. Despite some differences with Robespierre, Danton shared the same convictions: he voted for the death of the king and was in favour of the Terror. However, he dissociated himself from Robespierre's group. This is why he was arrested on March 30, 1794 and sentenced to death. He was guillotined on April 5, 1794.

Saint-Just was the son of a farmer who had trained in law. His ideas were strongly inspired by Machiavelli, Rousseau and Montesquieu. He condemned the monarchy and the aristocracy. In 1791, he was elected to the Legislative Assembly, but was too young to remain there. He sided with Robespierre, Danton and Marat. Despite his young age, Saint-Just was one of the main speakers at the Convention. He also played an important role in drafting the Constitution. He supported Robespierre to the end, and was guillotined at the same time as Robespierre on July 27, 1794.

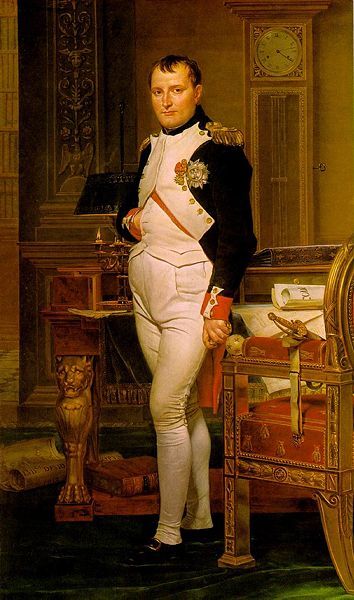

Napoleon Bonaparte was trained in the army. During the Revolution, he supported the Montagnards and Robespierre, but managed to be forgotten when Robespierre and his supporters were executed. Thereafter, Bonaparte distinguished himself in battle, waging very good war campaigns and always returning victorious. This is why the groups plotting against the Directoire government chose him to organise the coup d'état.

Following the coup d'état of 18 Brumaire, Napoleon became First Consul and held sole power. Napoleon's ambitions did not end there: he was crowned emperor on December 2, 1802, without opposition. During his reign, he implemented grandiose projects in Paris, such as the Arc de Triumphal. What's more, his measures greatly improved the living conditions of the population. In 1812, Napoleon attempted a military campaign in Russia, but failed. In 1814, the city of Paris had to capitulate and Napoleon was sent into exile. He tried to return, but suffered a dismal defeat at Waterloo in 1815. He retired and died in 1821.

A number of events occurred in rapid succession during the French Revolution, and many of them had a major impact on the lives of the French people.

- The French acquired freedom of thought and religion.

- The privileges of the nobility were abolished.

- France adopted the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

- The départements were created, making it easier to administer the country.

- The French introduced a new democracy.

- The bourgeoisie profited from the elections and grew rich.

- The Revolution caused wars that lasted from 1792 to 1815 and resulted in around 1 million deaths.

- The Revolution degenerated into bloody dictatorships (Robespierre and Napoleon).

- More than 20,000 people were guillotined.

- Civil wars, including the Vendée War, claimed 150,000 victims.

- The revolutionaries were great obstacles to the Catholic Church, even going so far as to ban worship.

- The nobility was persecuted and many had to go into exile.

- The commoners gained nothing from the revolution, only the bourgeoisie. The commoners even felt cheated and fooled.

- Several other popular uprisings followed the French Revolution: 1830, 1848, 1870, 1936 and 1968.