In the early 1830s, Lower Canada was in the midst of political, social and economic difficulties, leading to increased protests among the Canadiens and, ultimately, to the rebellions of 1837 and 1838.

In the early 1830s, there were numerous debates between the Canadien and British representatives in the Legislative Assembly. These debates often centred around financing canals, collecting duties and using subsidies.

Subsidies are grants (funds) that the government gives to companies or individuals to support them. The money for subsidies comes from taxes imposed by the Legislative Assembly.

The anger of the Parti patriote was fuelled by many issues. First, there was the absence of ministerial responsibility, which the governor refused to grant. The governor also had the ability to use his right of veto to overturn decisions made by the members. Members of the Legislative Council were not elected, but instead directly appointed by the governor himself and some corrupt members of the government, called the Château Clique, took advantage of the governor's favour towards them.

In 1826, the Parti canadien changed its name to the Parti patriote and adopted a more radical approach.

Various events caused tensions to rise between the French-Canadian and British populations of Lower Canada.

In 1832, a riot broke out during a by-election between a member of the Parti patriote and a member of the British Party. British army soldiers opened fire on the crowd and killed three Canadiens. After the incident, Parti patriote members demanded that a public inquiry take place, but the governor refused. The soldiers involved suffered no consequences, causing outrage among the Canadiens.

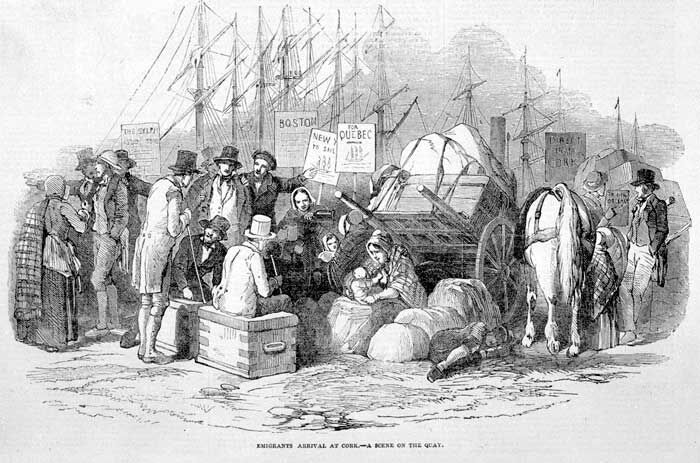

Furthermore, British immigration was soaring in the 1830s, and the Canadiens feared assimilation. These waves of immigrants were also the origin for the cholera epidemic that killed thousands between 1832 and 1834.

In the 1830s, Lower Canada was plagued by an agricultural crisis and overpopulation of seigneurial lands. As a result, many Canadiens suffered from famine, but the British authorities refused to create new seigneurial lands, allocating new townships to the British instead. Together, these factors caused growing dissatisfaction among the Canadiens.

In 1834, the members of the Parti patriote wrote the 92 Resolutions and sent this official document to London. Among the grievances it listed, the document criticized the way the corrupt political system favoured the British minority, as well as the colony’s ineffective administration and justice system. Based on the 92 Resolutions, the Parti patriote presented their demands.

|

That same year, the people of Lower Canada, including many Anglophones, threw their support behind the Parti patriote and elected it to a majority in the Legislative Assembly.

In 1835, a new governor replaced Lord Aylmer. London finally responded to the 92 Resolutions in 1837, by sending its own: the 10 Russell Resolutions. All of the Parti patriote’s demands were rejected. What’s more, the governor now had the authority to take money from the Legislative Assembly’s budget without its consent. This caused the Legislative Assembly members to lose the only leverage they had with the governor. Because of these reasons, the Parti patriote did not respond well to the 10 Russell Resolutions.

In 1837, Parti patriote members organized several popular assemblies in Lower Canada. At these assemblies, the Patriotes denounced the 10 Russell Resolutions and the government’s policies in front of crowds that numbered in the hundreds, and sometimes thousands.

Louis-Joseph Papineau, the leader of the Parti patriote, encouraged the people to boycott British products. This measure was meant to harm British merchants and deprive the colonial government and British Crown of taxes and duties.

On October 23 and 24, 1837, over 5 000 people attended the Assembly of the Six Counties, held in Saint-Charles-sur-Richelieu. Papineau advocated for a peaceful approach, but some members of the Parti patriote felt that it was time to take up arms, as Wolfred Nelson proclaimed during the same meeting.

Fearing an uprising, Governor Gosford banned popular assemblies in June 1837, which only served to further increase tensions between the Parti patriote and British authorities. The Assembly of the Six Counties and a violent brawl that broke out two weeks later in Montreal led to the arrest of 26 Patriote leaders on charges of high treason.

The upper and lower Catholic clergies had differing opinions on the rebellion, which created division within the Church.

The upper clergy, including influential members such as the bishop, openly opposed the Parti patriote’s demands and liberal ideas. The Bishop of Montreal, with the help of some of the parish priests, instructed people to respect the British authorities and the mother country, threatening to excommunicate anyone who took part in the rebellions.

Other parish priests and members of the lower clergy had a more nuanced view on the matter. Some priests supported the Parti patriote and even participated in popular assemblies.