In 1836, in response to the Patriote movement, young Anglophone Loyalists founded a radical group called the Doric Club.

The following year, as a form of backlash against the Doric Club, nearly a thousand young Canadiens came together to support the Patriote cause. Inspired by the American Revolution, they formed a movement they called the Fils de la Liberté (Sons of Liberty).

On November 6, 1837, following a meeting of the Fils de la liberté in Montreal, a violent fight broke out between them and members of the Doric Club. Only two weeks had passed since the Assembly of the Six Counties, so the governor of the colony responded to this event by issuing 26 arrest warrants for influential members of the Parti patriote, including their leader, Louis-Joseph Papineau. While numerous Patriotes were arrested and imprisoned, many of them, including Papineau, fled to the countryside and the United States.

The Patriotes organized their resistance in Saint-Eustache and the Richelieu Valley. Meanwhile, the British army had soldiers stationed in the area, reinforced by Loyalists who joined their ranks, and also relied on support from Upper Canada and Nova Scotia. All in all, some 3 000 soldiers were mobilized to stop the Patriote rebellions in Montreal and Quebec. In mid-November, the British military was ordered to put an end to the movement and to arrest the Patriotes who had warrants out for their arrest but had not surrendered.

The Patriotes were ill-equipped. Since some did not have guns during combat, families had to melt their pewter spoons to make bullets. The first battle took place in Saint-Denis on November 23, 1837. British soldiers attacked the rebels in the freezing rain, but the rebels managed to fend off the attackers by barricading themselves. The British retreated once they realized that the battle was not going as planned. This was the only major victory for the Patriotes.

Several battles and conflicts ensued in the weeks that followed. Martial law was declared, allowing British authorities to immediately arrest and imprison anyone suspected of supporting the Patriotes.

Martial law can be invoked by a government during times of war or crisis. Under these circumstances, the legal system is suspended and the military has authority over the people.

British forces pillaged, looted and burned some villages, including Saint-Charles and Saint-Eustache. Men, women and children were attacked and left out on the street in mid-winter, their belongings stolen and their homes burned down. As a result, hundreds of Patriotes fled to the United States.

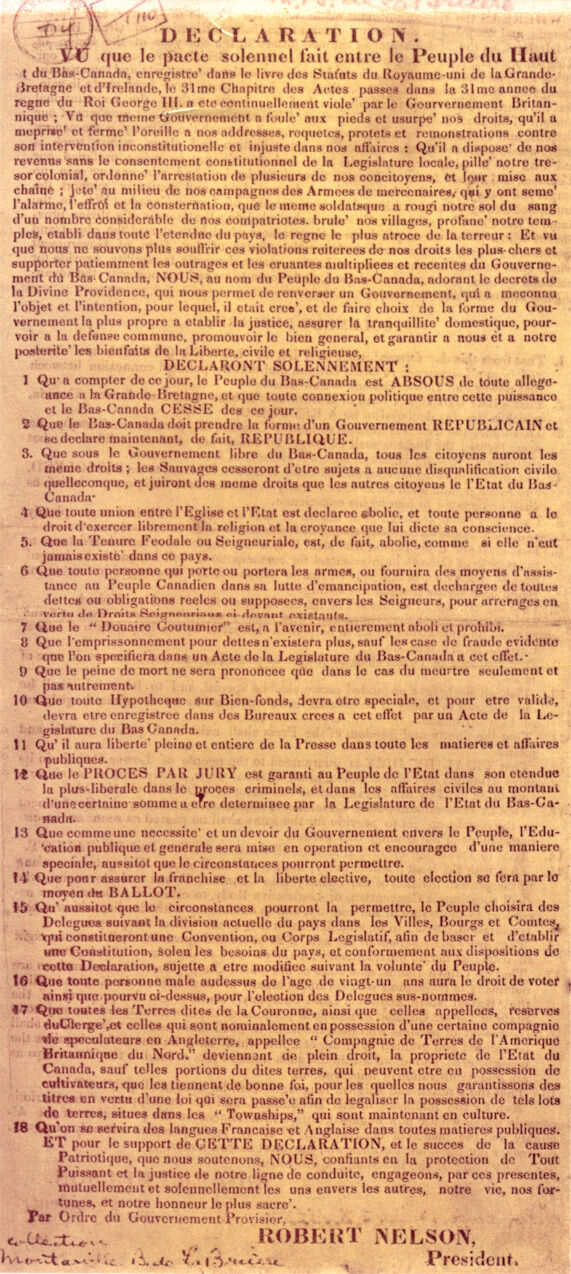

In early 1838, exiled Patriotes began to organize in the United States. Being more moderate than many of his compatriots, Papineau kept his distance, and Robert Nelson took his place as leader of the Patriotes. The Patriotes demanded Lower Canada’s independence and called for a resumption of hostilities against the British army.

On February 28 of the same year, Nelson and some 300 Patriotes returned to Lower Canada to declare the independence of the Republic of Lower Canada. When Nelson and his people were stopped by British troops, they retreated to the United States once again. Lower Canada’s independence was by no means settled, and Nelson was not ready to stand down. He founded the Frères chasseurs, a secret organization created to recruit people ready to keep fighting for independence and provide them with weapons.

On February 10, 1838, a few days before the Declaration of Independence, the British Parliament suspended the constitution because the Patriotes were still considered a threat. The governor of the colony formed a special Council of about 30 men appointed by him to provide guidance. Elected members of the Legislative Assembly were not invited to be a part of this Council.

During the spring and summer of 1838, the two sides got organized. In November 1838, Nelson returned to Lower Canada with the Frères chasseurs and broke out in the south of the colony. However, the British army had many reinforcements and a final defeat at Odelltown on November 9 ended the fighting between the Patriotes and the British troops. The rebellion had failed.

With martial law still in force and the constitution still suspended, the British authorities tried the 108 Patriotes accused of sedition and high treason. Of the Patriotes put to trial, 99 were sentenced to death. Twelve of these men were publicly hanged, and the other 87 escaped their sentences.

Sedition is the act of organizing a revolt against an established authority.

Even though the rebellion was over, the constitution was still suspended as the authorities were waiting for the British Parliament to make a decision on its colony before reinstating the constitution. Appointed governor in 1838, Lord Durham was given the mandate of finding a way to peacefully govern Upper Canada and Lower Canada.

Some reformers in Upper Canada criticized the inequalities that remained throughout the colony. They considered it unfair that a closed group of influential people, known as the Family Compact, took advantage of their close relationship with the governor to control the colony’s administration and trade. This was very similar to the situation occurring at the same time in Lower Canada with the Château Clique.

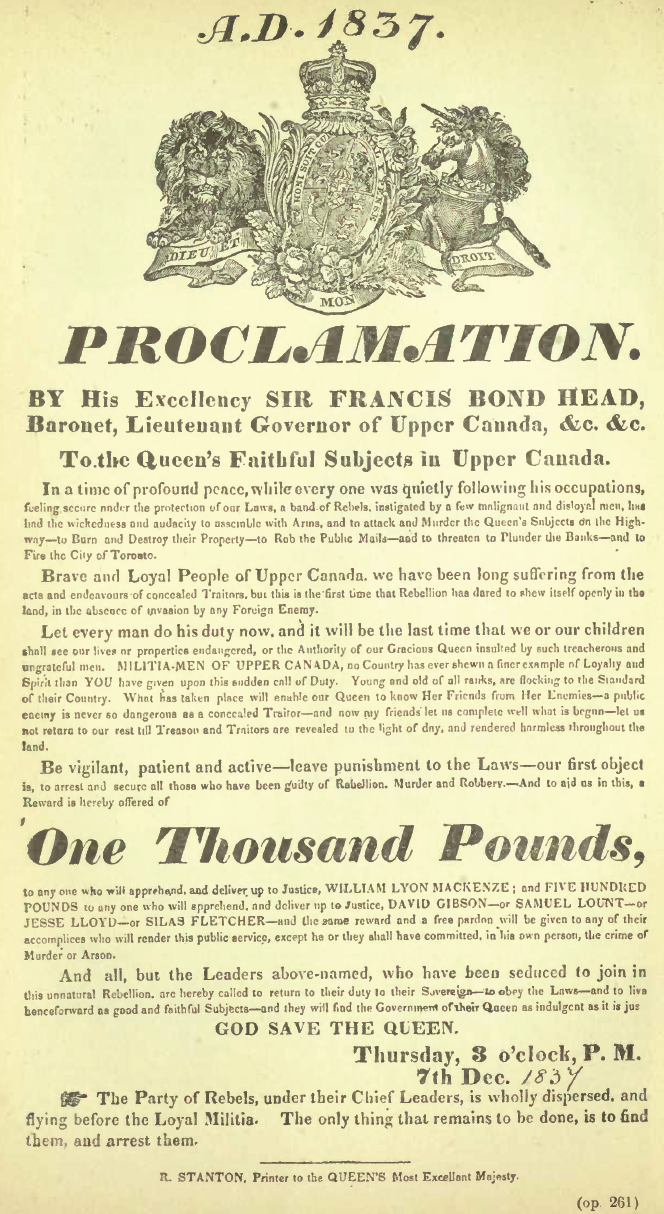

William Lyon Mackenzie, who was a member of the Legislative Assembly, realized that British forces were quite busy suppressing the Patriote rebellions and that it was the right time to make a move. In December 1837, he started organizing popular assemblies to encourage his fellow countrymen to rise up against the injustices in the colony.

As a result of these efforts to mobilize, a group of a 1 000 rebels decided to overthrow the government of Upper Canada by force. The rebels attempted to take over the city of York (now Toronto), but fled after being driven back by citizens who did not support the revolt. Indeed, these rebellions received much less support from the population than the Patriotes did in Lower Canada.