Before colonization, the Rwandan people were all part of a single ethnic group: the Banyarwanda. They shared one language, one religion, one territory and practised the same customs, however their society was divided into economic categories. There were already tensions between certain groups in the population.

Germany began to colonize Rwanda towards the end of the 19th century. The German colony was seized by Belgium at the beginning of the 20th century.

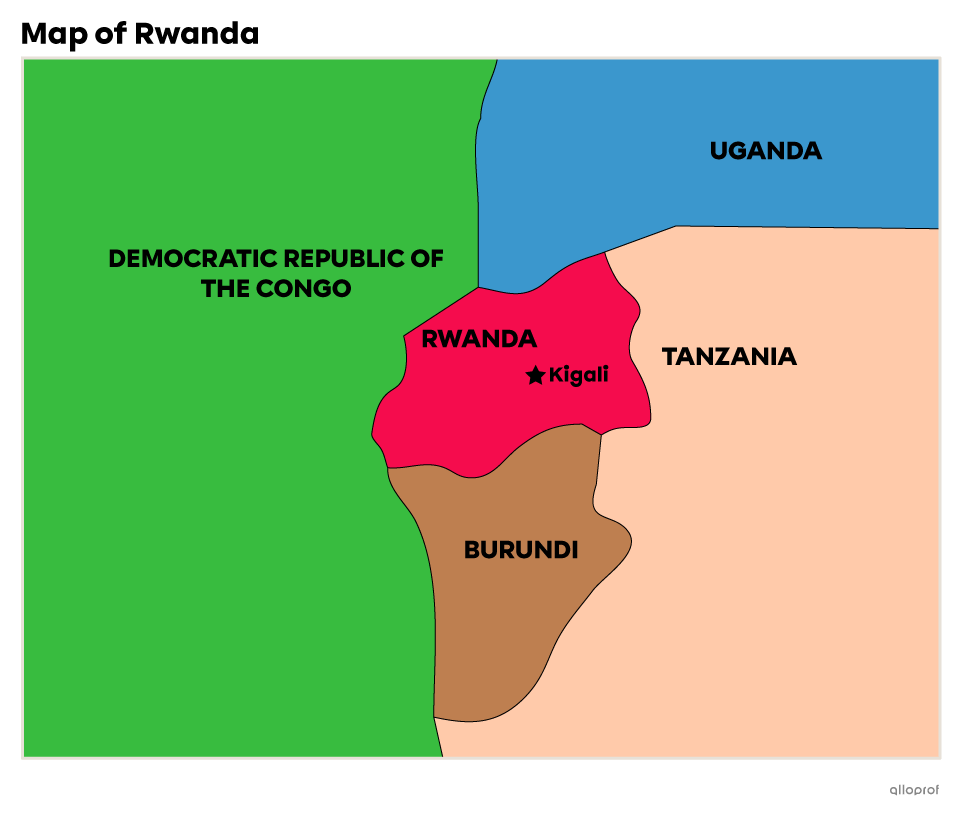

Rwanda is nicknamed “land of a thousand hills”.

The Belgians saw two significantly different social groups: the Tutsis and the Hutus.

In 1930, based on the physical differences between the two groups, the Belgians declared that the Tutsis were superior to the Hutus because of their more refined features and lighter skin.

In 1945, the Belgians instituted registration cards which included a designated ethnicity. The use of these cards brought about increased tensions between the Hutus and the Tutsis. Towards the end of the 1950s, the Tutsis demanded the independence and secularization of Rwanda.

The Tutsis were favoured by colonial powers, yet the Hutus represented the people of the nation. The clergy began granting more powers to the Hutus and supported the supremacy of the Hutus, since they represented most of the population at 85%. This change led to new, even more intense tensions, causing racial hatred.

The Hutus rebelled against the colonial power in 1959 and massacred the Tutsis. Many Tutsis then left Rwanda.

Rwanda obtained its political independence in 1962. The difficulties between the Tutsis and the Hutus were still present and led to new massacres. The exiled Tutsis attempted an offensive that was met with heavy reprisals causing many Tutsis to die or flee.

Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu, led a successful coup d’État that brought him to power. He instituted a new constitution in 1978. This constitution continued the use of the identity registration card.

Juvénal Habyariman

A Tutsi guerrilla war was organized from Uganda in 1987. The Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) came on the scene in 1990. At the same time, the incumbent powers were preparing to arm and train a military junta, planning the murder of the Tutsis.

This training and propaganda continued throughout 1993. Leaders encouraged Hutus to massacre the Tutsis. Radio and television were used to broadcast these calls to violence. These messages called Tutsis vermin to be exterminated by any means. Foreigners who were in Rwanda at that time witnessed the increase in violence and knew that a genocide was on the way. Many of them left the country in order to avoid being caught up in what was to come.

An unforeseen event on April 6, 1994 caused the onset of the massacre. President Juvénal Habyarimana died when his airplane crashed. The odd circumstances surrounding this accident have never been brought to light. The announcement of this death was immediately followed by the assassination of some of the most influential members of the opposition.

The massacres began on April 6. The militias had been prepared, and they were trained and armed. A list of persons to be eliminated had been prepared. This list targeted mainly the Tutsis, but also the Hutus who were connected to the Tutsis (through marriage, co-habitation, economic alliance, support of the genocide, etc.).

The militias blocked all the streets of Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, on April 7, 1994. This was the beginning of the genocide and massacres.

UN troops had to be evacuated because of the increasing violence. Only a few soldiers were left behind. Once these troops had departed, the Rwandan militias were free to do as they pleased. The massacres lasted 13 weeks. The militias went hunting for Tutsis every day and by the end, some 800 000 Rwandans had been violently slaughtered. In total, 75% of the Tutsi population was eliminated by machete or clubbing during these few weeks.

Hatred resulting from the years of division between the Tutsis and the Hutus literally exploded. The militias tortured and raped their victims. The Tutsi RPF guerrilla movement charged on Kigali in July 1994 and hunted down the Hutu government. The government leaders and perpetrators fled Rwanda.

Paul Kagame established a new government to unify the nation, ending the genocide. Rwandans had to rebuild their country, which had been ravaged by death and hatred.

The new government wanted national unity but could not achieve it quickly. Towards the end of the genocide, some Tutsis perpetrated violent acts of revenge against the Hutus.

The Hutu and Tutsi populations had to learn how to live with each other again, executioners rubbing shoulders with survivors as well as the families of their victims. Rwanda also had to organize legal proceedings for the 112 000 detainees who were suspected of participating in the massacres. The UN was responsible for setting up an international crimes tribunal to try those who played a key role in the genocide. Overcoming the desire for revenge proved to be the biggest problem for this tribunal. The courts also had to confront the issue of personal responsibility, both for orders given and for incitement to violence.

Rwandans established traditional courts, where sentences were handed down by both the judge and the community. This was intended to prevent lapses in justice. These open-air courts sought a quicker judgement but, above all, wished to facilitate reconciliation among Rwandans. This type of trial handed down reduced sentences to defendants who showed remorse for their actions. The death penalty was never used in any of these cases. A number of foreign attorneys took part in these trials in order to be sure that the defendants had a fair defence. The genocide is still a taboo subject in Rwanda today.

The world was appalled by the reports of genocide. Everyone wondered whether this disaster could have been prevented and the answers were most disconcerting. When the massacres occurred, and even long before, the international community had been aware of what was brewing in Rwanda. The peacekeepers (Casques Bleus) who were there in 1993 had warned the UN and foreign countries.

There were nearly 2500 UN soldiers in Rwanda before the onset of the massacre. They intervened to facilitate agreements between the sitting government and the RPF. Nonetheless, after the beginning of the massacre, the UN withdrew its troops, leaving only 200 soldiers. Rather than protecting the threatened population during the massacre, these soldiers focused on the emergency evacuation of the last foreigners present.

It was on May 16th that the UN sent 5500 peacekeepers (Casques Bleus) to defend Rwandan civilians. The word “genocide” was never uttered during the massacre. The UN later acknowledged its responsibility for the genocide, stating it had not done enough.

After the events, France was also accused of having helped prepare the genocide by collaborating with the Rwandan government to promote the arming and training of Rwandan troops. A number of countries, including Belgium and the United States, later acknowledged their share of responsibility for the genocide. In 2004, the UN appointed a Special Adviser on the Prevention of Genocide.