In the 19th century, women had a very limited place in society, both in Quebec and elsewhere in Canada. They were often reduced to being a daughter, a wife or a mother, and they were scarcely present in other spheres of daily life: right to vote, personal finances, legal status, right to higher education, among other things.

Under the Constitutional Act of 1791, all “landowners” had the right to vote, allowing some women who owned property to vote, even if many did not actively participate in politics.

When politicians, with the clergy’s support, recognized this loophole in the Act, they decided to “correct” the situation. In 1849, Parliament changed the text of the law to specify male landowners only, effectively withdrawing the right to vote from women who were previously eligible.

Legally, women were considered children in the eyes of the law, and their rights were limited.

-

Before she married, a woman was under her father’s responsibility. Once married, she was under the authority of her husband

-

After marrying, she had to use her husband’s first and last names on official documents. For example, she would become Mrs. Marcel Brousseau

-

She could not have a bank account in her name

-

She could not take somebody to court

-

Her husband chose where they lived

-

If a man was found guilty of adultery he had to pay a fine, whereas a woman in the same position was imprisoned

-

She could not be the only person responsible for minor children

The legal restrictions meant women were very vulnerable and dependent on the men in their family.

As they had no access to higher education, women’s job opportunities were limited. The few young women who were educated could not access high-level jobs, and their choices were often limited to roles as secretaries or assistants.

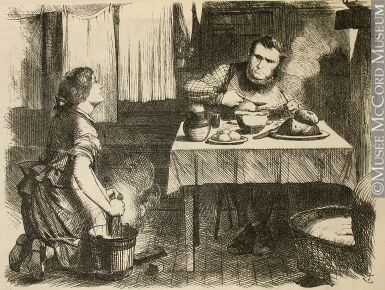

Those who did not have educational opportunities often turned to manual labour, even though society generally frowned upon it and working conditions were poor. Women’s wages were often lower than those of a man doing the same job, and husbands also had the right to manage their wife’s earnings. If they decided to work, women still had to take care of the house and educate their children.

In addition to manual labour, some women opted for traditionally female jobs such as teaching, sales and secretarial work. Women who stayed at home could also do small jobs like ironing or sewing to make a little money.

The Church was omnipresent, leading to the creation of many religious communities. These communities worked in healthcare and education as well as several other social spheres, such as running soup kitchens, orphanages or daycares.

Belonging to a religious community was highly regarded in society, and it allowed women to participate in public life. It also meant that they could obtain higher positions, such as school principal or administrative jobs. However, women who decided to join a religious community had to renounce the right to get married.

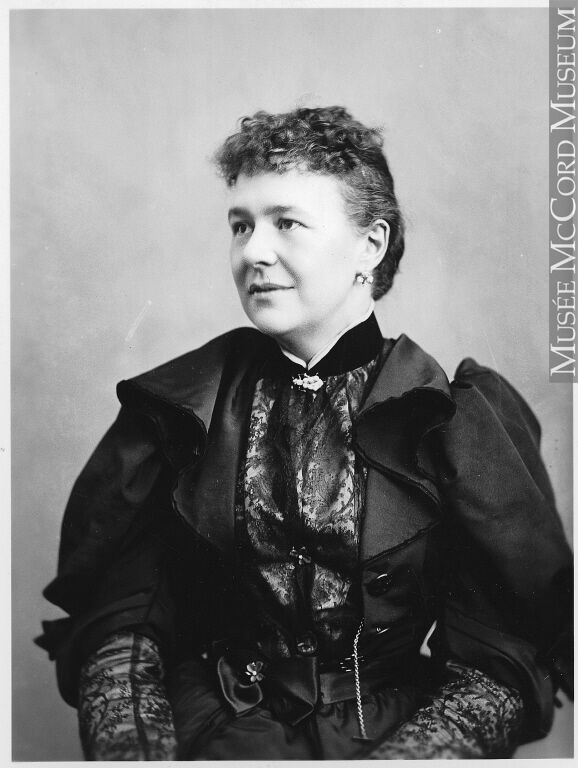

Over time, some women decided to band together to form associations to promote some of their rights. This was the beginning of feminism. The founders of these associations were often middle-class Anglophones who wanted to help society and promote women’s rights. The priorities for women were the right to vote, access to higher education, improved working conditions and social services (e.g. fighting poverty) and healthcare.

These middle-class women founded organizations to support women’s rights and education, among others. As an example, the YWCA (Young Women’s Christian Association) had centres where women could access public libraries and evening classes to improve their education. The first centre opened in 1870 in New Brunswick and another opened its doors in 1874 in Montreal. Meanwhile, the MLCW (Montreal Local Council of Women) was created in 1893 to defend the rights of female workers. Other organizations emerged over time.