To access the other concept sheets in the unit on Tourism, consult the See Also section.

A lagoon is a body of water separated from the sea by a barrier beach (a strip of land away from the coast).

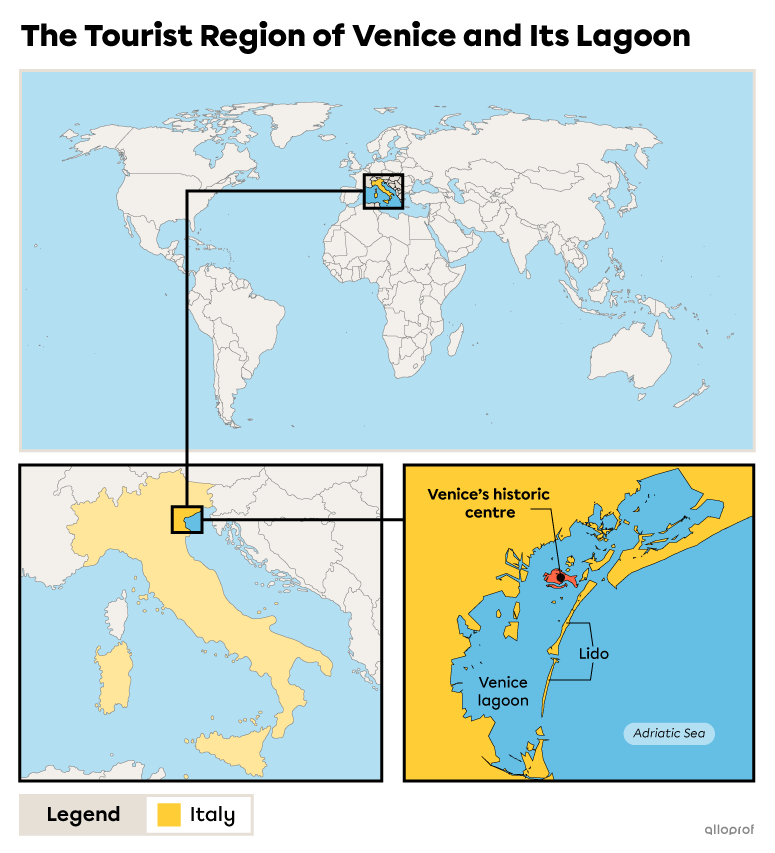

Venice is a city located in northeastern Italy in a lagoon. The strip of land separating it from the Adriatic Sea is called the Lido. There is water all around the city and flowing through the city. The centre of Venice is built on numerous islands surrounded by canals that people use to get around. The centre of Venice covers a total area of 8 km2 [1].

The city of Venice is crossed by 177 canals on which it is possible to travel by boat[2].

Source : RAW-films, Shutterstock.com

The city of Venice is one of the world's most popular tourist destinations. Listed on the UNESCO World Heritage List, it welcomes approximately 30 million visitors[3] each year.

The city's history and architecture attract many culture tourism enthusiasts. The city was founded in Ancient times and was a highly influential merchant city during the Medieval and Renaissance periods. Venice also has the distinction of being built on water, which makes it one of a kind.

The city offers a multitude of cultural attractions, including monuments, museums and festivals.

The Doge's Palace, also known as Palazzo Ducale, was long the residence of the Doge, the head of the Venetian Republic. The palace was therefore also the seat of government. The palace's architecture is a blend of Gothic, Byzantine and Renaissance styles.

Source : Roman Sigaev, Shutterstock.com

St. Mark's Basilica was the centre of religious life in Venice for a very long time. Its construction began in 1023. Its blend of Byzantine, Roman and Venetian architectural styles greatly impresses visitors. The Campanile, the basilica's bell tower, is also a popular tourist attraction, as visitors can climb it and see the city from another angle.

Source : Catarina Belova, Shutterstock.com

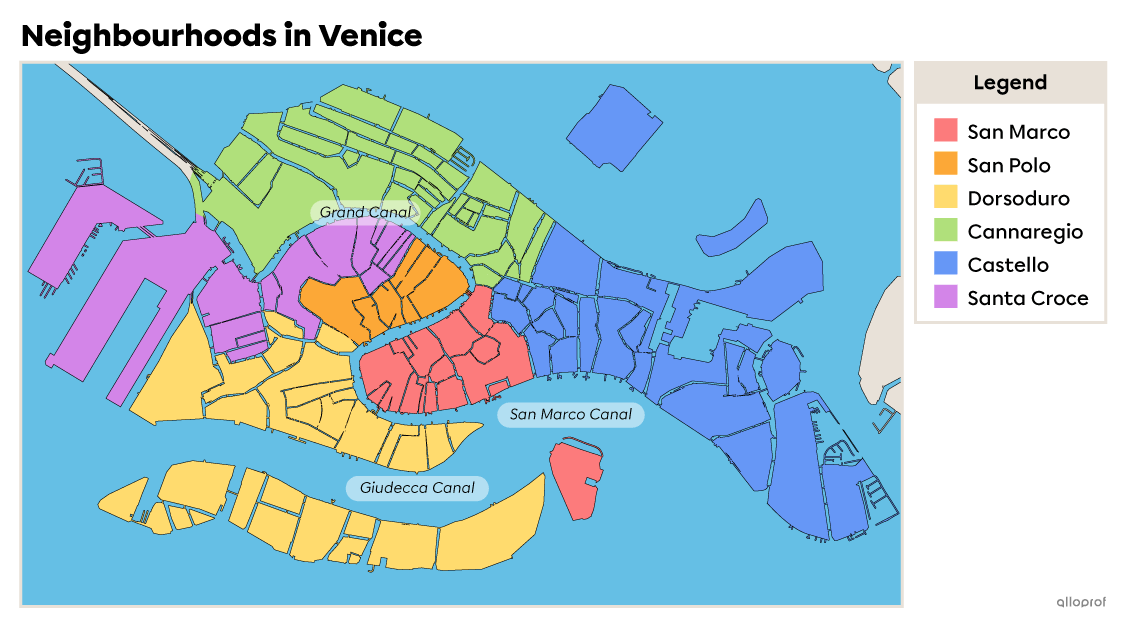

Piazza San Marco is home to the Basilica, the Doge's Palace, the Museo Correr, the Campanile and the Torre dell'Orologio (clock tower). The piazza is 180 by 70 metres[4]. During the acqua alta (high tide), Piazza San Marco is often the first to be flooded since it is located at the city's lowest level.

Source : Andrew Mayovskyy, Shutterstock.com

The Grand Canal lets you explore Venice from the water. It is the city's largest and most important canal. 4 km long, it divides the city into two[5]. There are four bridges across the Grand Canal, the best known being the Rialto Bridge.

Source : Simone Menegari, Shutterstock.com

The Rialto Bridge, built between 1588 and 1591, is the oldest bridge to cross the Grand Canal. The three-staircase bridge is lined with various souvenir shops.

Source : Tomas Marek, Shutterstock.com

As the city of Venice is located on an archipelago, the city's infrastructure and developments must be adapted to this particularity. The city is made up of a hundred or so small islands. There are no roads or highways, since Venice is built on water. Transportation is by boat or on foot. For those traveling on foot, some 400 bridges link the various islands together. For travel on water, there are various means of transportation:

- gondolas and traghetti

- water cabs

- vaporettos

Venice offers a wealth of accommodation options. There are over 380 hotels in the city, in addition to hostels, B&Bs and Airbnb rentals. There's also an impressive number of restaurants in the city, which exceeds 1500[6].

Various events are organized to attract tourists, such as the popular Venetian Carnival.

The vaporetto is the most popular means of transportation in Venice. These boat-buses are used as much by the local population as by tourists. City services (police, ambulance, post office) also use this means of transportation . The vaporettos average 24 m in length and can accommodate about 200 people.

Source : vvoe, Shutterstock.com

The gondola is a traditional means of transportation in Venice. For hundreds of years, it was the main means of getting around the city. Today, it's used mainly by tourists. The gondola is a boat, rather long and rather narrow, which is powered by a single oar.

Source : Parilov, Shutterstock.com

Venice's Carnival appeared in the 11th century. The purpose of the Carnival at this time was to celebrate the greatness and power of the city of Venice. The festival was also a unifying moment for the city's various districts. In 1970, the Venice Tourism and Culture Office launched an advertising campaign to promote the Carnival. Today, the Carnival is held in February. People in costumes and masks take to the streets, and balls and parades are organized.

Source : Pajor Pawel, Shutterstock.com

The Floods

Over the years, the city of Venice has experienced several floods. As the city is built close to the water level, it is more at risk of flooding as soon as the water level rises due to large tides. A large tide is also called acqua alta (acque alte in the plural).

The number of floods has increased greatly in recent decades, becoming a greater threat to the city's future. Several measures have been taken to try to protect Venice from rising waters.

In 2003, a major project was launched: the Modulo Sperimentale Elettromeccanico, often referred to as MOSE or Moses. The aim is to protect the city by installing a system of dikes at the entrances to the lagoon.

These dikes are mobile. Normally, they remain closed, but when the water level rises too high, they rise to the surface. This forms a dam that prevents the water level in the lagoon from rising.

Deployed for the first time in 2020, the MOSE system has proved its effectiveness on several occasions since then, saving Venice from numerous floods.

The dikes are the result of an enormous amount of work. They stretch over 2500 metres and cost over 5 billion euros to build[7]. They are also very expensive to monitor and maintain. For the time being, however, they are able to help protect the city.

The Venice lagoon is home to marshes. Thanks to the roots of plants, these marshes help protect the coast from erosion. They are also capable of capturing large quantities of CO2 from the air, helping in the process to reduce air pollution.

The marsh ecosystem feeds on sediments brought in mainly by high tides. However, now that dykes are blocking these high tides, less sediment is reaching the marshes. This could lead to their disappearance. One proposed solution is to wait until the tide is a little higher before activating the dikes. The city would then experience slight flooding, but the marshes would get the sediment they need to survive.

Erosion is the degradation of soil by wind, water or human action.

In less than a week, in November 2019, the city of Venice was flooded by 3 episodes of acque alte. The floods caused a lot of damage to public places, hotels, churches and homes. It also caused at least one death. At the height of the flooding, 80% of the city was inundated[8].

Source : Ihor Serdyukov, Shutterstock.com

The Sinking City

The city of Venice has been sinking into the ground for several decades. This means that it is lower and lower in relation to sea level, increasing the risk of flooding and endangering the city's buildings.

One of the causes of this subsidence is that, in the past, groundwater was pumped beneath the city. Removing this water weakened the soil supporting the city, accelerating the sinking process. Since 1970, it has been forbidden to pump groundwater. This ban has helped stabilize the city. Nevertheless, the city continues to sink into the ground.

Air Pollution

Air pollution is accelerating the deterioration of the city and its tourist attractions.

The use of diesel-powered boats throughout the city pollutes the air. This polluted air attacks stone and other building materials, slowly destroying them. For example, palaces near the Grand Canal are affected by pollution from the high number of boats.

Source : Alex Fonda, Shutterstock.com

The city of Venice is implementing a number of measures to reduce pollution and protect its attractions. One of these measures is to use less polluting energy sources, such as electricity or even hydrogen. The city is also taking steps to reduce the pollution produced by waste left behind by tourists. Among other things, it encourages them to use water fountains instead of taking disposable water bottles.

The Impact of Cruise Ships

In 2019, the port located in the centre of the city of Venice welcomed 667 cruise ships totalling roughly 700 000 passengers[9]. These ships move through the heart of the city. Many are so large that they tower over all the buildings around them. As they move, they pass very close to historic buildings and monuments such as the Doge's Palace and Piazza San Marco. Their presence has many impacts, both on the lagoon's environment and on the city and its heritage.

One of these impacts is the effect of the waves created by these boats on the city's foundations. Venice is largely built on wooden foundations sunk into the ground. Waves hitting the banks weaken these foundations, endangering the buildings built on them.

Another impact is pollution. Cruise ships bring:

- air pollution from their engines

- visual pollution, given their size and presence in tourist attractions

- noise pollution from their engines and on-board activities

Because of their size, cruise ships are clearly visible through the buildings of Venice.

Source : volkova natalia, Shutterstock.com

Thousands of jobs in the region depend directly on the presence of cruise ships, and many more depend on the presence of tourists. So it's not so easy to put this industry on the back burner.

Faced with several pressures, including UNESCO's threat to add Venice to the List of World Heritage in Danger, the authorities banned certain large ships from entering the city in 2021. For example, ships longer than 180 metres or whose emissions contain more than 0.1% sulfur can no longer circulate in the city and dock at the Port of Venice. They must go to another port in the region. Smaller cruise ships, on the other hand, can still dock in the port of Venice.

However, some argue that cruise ships should be banned not just in Venice, but in the entire lagoon, in order to truly protect the city and its surrounding ecosystem.

By 2020, containment measures had significantly reduced the number of trips into the city. The water in Venice's canals, generally cloudy due to the passage of many boats, became clear. Sediment suspended in the water settled to the bottom. It was therefore possible to see the bottom of the water and the marine fauna found there. These changes in the city's environment have raised several questions in connection with the development of tourism in Venice.

Venice welcomes over 30 million tourists every year. On the busiest days, that's 150 000 tourists visiting the city in one day[3]. This not only causes enormous pressure on the environment and the city itself, but also several issues for the local population.

In 1980, over 100 000 people lived in Venice's historic centre, whereas today there are fewer than 52 000[10]. In almost 40 years, the city has lost half its population. This massive departure of residents can be explained in different ways. Some people decide to leave, others are forced to leave.

Venetians Are Leaving the City in Search of a Better Quality of Life

With 30 million tourists for 52 000 inhabitants, many infrastructures and facilities are thought out in terms of the needs of tourists rather than the needs of locals.

One example of this is the types of shops present in the city. A large number of stores dedicated to tourists are opening their doors (such as souvenir shops) at the expense of shops that cater to the needs of local residents (bakeries, hardware stores). Residents are therefore leaving the city, as they are no longer able to find services that meet their needs.

Another reason for these departures is the rising cost of houses, accommodation and products and services (food, transport, etc.) caused by mass tourism. Living in Venice is becoming too expensive, so locals are leaving in search of a more affordable place to live.

The high number of tourists also causes many inconveniences for the locals:

- constant noise

- congestion in streets and canals

- huge crowds in public places

- garbage

Traffic jams caused by tourists are so numerous that locals have to adapt their movements to avoid the busiest streets. It sometimes becomes impossible to cross a bridge when there are too many tourists stopping to take photos.

Venetians Forced to Quit the City

Many Venetians are also forced to leave Venice after being evicted from their homes. In fact, many homes in Venice's historic centre are being bought up and turned into hotels or residences for tourists (Airbnb). Residents are thus forced to move elsewhere. Between 1000 and 1500 residents leave the city every year[10]. They often choose to leave Venice simply because of the reasons mentioned above.

Solutions Are Difficult to Implement

Although tourism brings its own set of challenges, it remains the region's main economic sector. About 65% of the population of Venice's historic centre works in the tourism sector[11]. If we extend this to the outlying region, 100 000 people make their living from tourism in Venice[12].

The continued growth of the tourism sector is supported by the local authorities. However, measures are being taken to counter the negative effects of mass tourism. Here are just a few examples:

- A ban on cruise ships docking near the historic centre.

- The implementation of a video-surveillance system that makes it possible to recognize the number of tourists arriving in the city each day.

- The introduction of regulations for stores dedicated to tourists. The municipality intends to prohibit the opening of new low-cost souvenir stores. The aim is to encourage Venetian craftsmen and to open shops serving the local population, such as butchers, fishmongers and fruit and vegetable stores.

A recovery plan has been proposed in Rome. The plan calls for increasing the number of residents, limiting the number of tourist residences (such as Airbnb), controlling the number of day-trippers and better protecting Venetian artisans.

Implementing these measures can sometimes take several years. This is the case with the entry ticket project, otherwise known as a "tourist tax".

The Venice entry ticket is an idea that came about in an effort to counteract excess tourism. It makes it possible to predict how many tourists it would have each day. In addition, by increasing the ticket price on the busiest days, the authorities also hoped to better balance the flow of tourists throughout the year. The ticket would be required only for tourists coming for a single day. This means that tourists staying in Venice or the surrounding municipalities would be exempt from buying a ticket.

The idea had already been put forward before the COVID-19 pandemic. However, travel restrictions delayed its introduction. When tourist traffic returned to pre-pandemic levels, municipal authorities decided to relaunch the project. Here are some details about the evolution of the revised timetable:

- The right of entry was to take effect in June 2022. However, in May 2022, the municipality decided to postpone the project until January 2023.

- In January 2023, the project was postponed until summer 2023. The problem lies in the way tickets are controlled.

- Even in 2023, the project lowered its requirements: tickets will be compulsory only for a few days a year, i.e. the 15 or 20 days that are typically the busiest. All day visitors, on the other hand, will be required to reserve a free ticket. This will enable tourists to reserve their place, since the number of visitors will be limited.

- This new version of the project is scheduled to be tested in 2024.

- The tax will officially come into force in 2025.

To access the rest of the unit, please consult the following pages.

- Routard.com. (n.d.). Carte d’identité de Venise. https://www.routard.com/guide/venise/687/carte_d_identite.htm

- Larousse. (n.d.). Venise. https://www.larousse.fr/encyclopedie/ville/Venise/148536

- Ménage, F.-X., Lassalle, Lucas, Bedarida. Bernard. (2022, August 5th). Mesures financìères, traçage des touristes…Venise submergée par les visiteurs. TFI Info. https://www.tf1info.fr/international/video-venise-les-touristes-suivis-a-la-trace-2228400.html

- Civitatis Venise. (n.d.). Place Saint-Marc. https://www.venise.net/place-saint-marc

- Civitatis Venise. (n.d.). Grand Canal de Venise. https://www.venise.net/grand-canal

- Rabaudy, Nicolas de. (2016, August 28th). Venise ne connaît pas la crise. Slate. https://www.slate.fr/story/122663/hotellerie-venise

- Thibaut. (2022, May 12th). Barrage Venise : tout savoir sur le projet MOSE pour protéger la ville. Bonjour Venise. https://bonjourvenise.fr/barrage-venise/

- Le Parisien. (2019, November 16th). « Acqua alta » : déjà dévastée, Venise se prépare à une troisième grave inondation. https://www.leparisien.fr/societe/acqua-alta-deja-devastee-venise-se-prepare-a-une-troisieme-grave-inondation-16-11-2019-8194920.php

- Radio-Canada. (2021, June 5th). Venise : les croisières reprennent, de même que les manifestations. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1799210/croisiere-tourisme-masse-venise-italie-pandemie

- Alexandre Shields. (2019, December 2nd). Venise, une ville noyée par le tourisme. Le Devoir. https://www.ledevoir.com/monde/europe/568227/venise-une-ville-noyee-par-le-tourisme

- Gildas Le Roux. (2020, May 15th). Venise, une ville morte sans les touristes. La Presse. https://www.lapresse.ca/voyage/europe/2020-05-15/venise-une-ville-morte-sans-les-touristes

- Étienne Leblanc. (2020, June 11th). L’après-COVID-19 : réinventer Venise et son tourisme destructeur. Radio-Canada. https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/1709030/coronavirus-venise-tourisme-masse-francesco-bandarin-unesco