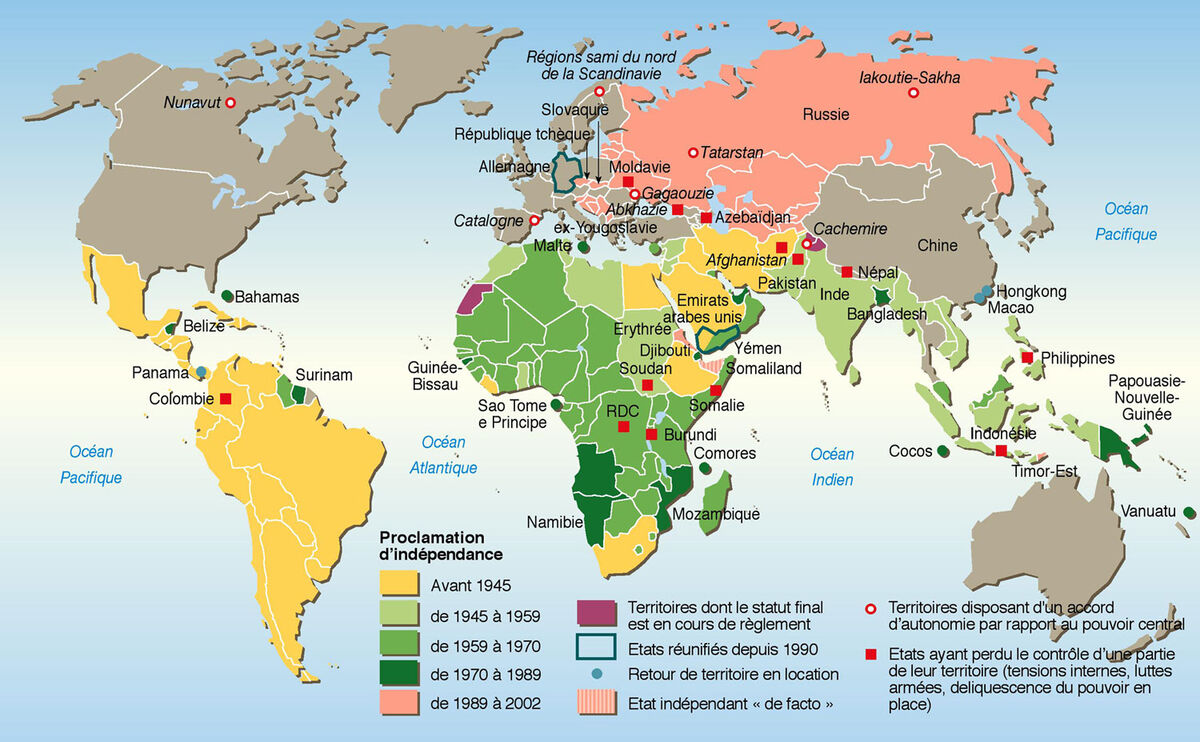

Decolonization is the process by which a nation gains independence and sovereignty over territories formerly administered by foreign colonizing powers.

The decolonization movements were very strong after the Second World War, when the great colonial empires of the 19th century had lost much of their influence. The peak of decolonization was therefore between 1945 and 1960. There are two types of decolonization: violent decolonization and negotiated decolonization. In the first case, decolonization is achieved after numerous demonstrations, riots or wars. In the second, the process of autonomy and independence is initiated by negotiations between the mother country and the colony.

Anti-colonialism stems directly from the colonial practices of the 19th century . Since then, a number of groups have protested against these practices. More specifically, anti-colonialism did not accept the right to conquer commoners or the people for the benefit of wealthy nations by force. People therefore called for insurrection and war so that the invaders would immediately evacuate the nation, leaving it free and sovereign.

Anti-colonialism is a political trend or attitude that questions the principles and existence of the colonial system.

The demands of anti-colonialism are strongly linked to nationalist sentiment. This is why the two movements often arrived simultaneously in the colonies. Nationalists criticised the imperialistic ambitions of the mother country and the consequences: repression, slavery, exploitation, disrespect for human rights and local culture.

By the end of the First World War in 1919, the great colonial empires were at their height. Their strength and wealth came directly from the overseas resources they drew from their colonies. However, between the wars, the first movements demanding autonomy and independence emerged. Led by educated elites, these movements protested in the name of democratic principles, valued by the mother countries and flouted in the colonies, as well as in the name of national identity, which was equally flouted. Despite these protests, the mother countries were still very strong on the eve of the Second World War.

At the end of the war, demands for freedom and autonomy resumed with renewed vigour. These movements gained momentum, and people were also critical of their inferior status under the system put in place by the mother countries. At the same time, the mother countries were experiencing divisions over the administration of their colonies. This internal division was compounded by pressure from outside countries and from the United Nations.

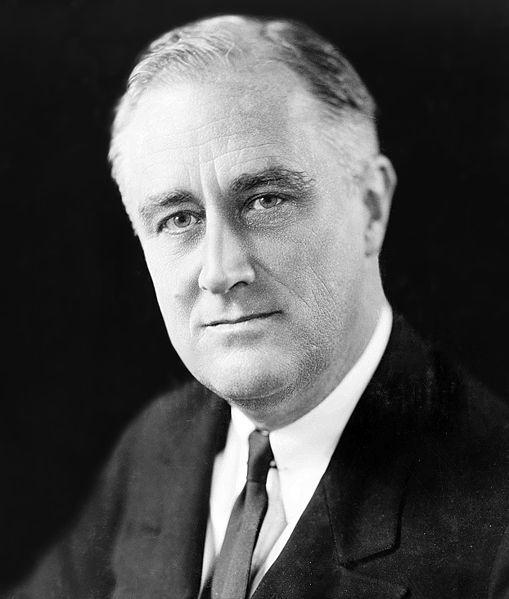

Back in 1942, the United States undertook to respect the right of each commoners or people to choose their own form of government and the free exercise of power. At the same time, the UN was promoting the equality of commoners or the people and their right to self-determination, and wished to set up processes for achieving independence. It was F. D. Roosevelt, then President of the United States, who declared that the commoners or the people had the freedom to choose their government.

The Soviet Union also encouraged the emergence of nationalist groups in colonised countries. The Communist parties of the Union offered a socialist economic model that served as a reference for the movements and the newly independent countries. Some communist parties even provided assistance to liberation movements.

Colonisation did not bring what the people expected, and despite the overall improvement in living standards thanks to the establishment of hospitals, schools, roads and the development of agriculture and industries, the colonised found that private and foreign interests benefited more from these new structures than the local population.

In several colonies, for example, the new administrators had eliminated local agriculture in favour of export crops that did not feed the local population. In fact, the colonised nations were critical of the fact that there was no real profit for them while the mother countries profited from the natural resources and became richer. Independence movements were also critical of social inequalities and laws that favoured one section of the population over another. This discontent was strongly expressed in a speech by Ho Chi Minh in 1945.

He drew on the United States Declaration of Independence and the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen to criticise the colonialist attitude that denied these rights to Vietnam. In the same speech, he announced the creation of a provisional government and affirmed the will of the commoners or the people to become freedmen. Vietnamese independence was underway.

After the Declaration of Independence of the colonies in Indochina, several independence proclamations were made. General Charles de Gaulle also tried to negotiate with Vietnam. The failure of these negotiations led France to take military action. This marked the start of the Vietnam War of Independence, which lasted 9 years. France's capitulation led to an election process that was aborted by the United States.

The commoners or the people of Asia were more easily emancipated. Having had their territory occupied by the Japanese during the war, they had acquired a stronger sense of nationalism, in addition to having received promises of autonomy from the United States during the war. The first wave of decolonization began at the end of the Second World War, in South-East Asia.

Note: English image coming soon!

Here are some of the independent nations born at this time:

- Philippines, 1946. Agreement with the United States: the Philippines received financial aid in exchange for rights to exploit natural resources. This agreement was supplemented in 1947 by a mutual defence pact.

- India, Pakistan and Ceylon in 1947. After clashes between two independence movements, the British colonies were divided into two countries. The partition was based on religion.

- Burma in 1947. Burma acquires its autonomy from Great Britain and excludes itself from the Commonwealth, an association of former British colonies.

- Indonesia, between 1945 and 1949. In 1945, Indonesia declared independence from the Netherlands. The mother country's refusal led to condemnation from the entire international community. The agreement was proposed by the British and the Americans. The independence processes were supervised by the UN.

Nationalist movements were born and spread to the other French colonies. The failure of the French army provided additional motivation for the independence movements. In 1956, France granted independence to Morocco and Tunisia, after the independence movements had carried out a terrorist campaign.

France then had to deal with the independence movements in Algeria and black Africa. A speech by Charles de Gaulle in Brazzaville, in which he promised greater autonomy for the commoners or the people, gave rise to the independence movements in Africa. In 1958, Charles de Gaulle gave the nations a choice between acquiring greater autonomy within the French community and becoming independent states. The majority of the colonies chose the second option.

In 1945, a third of the world's population lived in territories administered by colonial powers. At that time, this part of the population was not politically autonomous. The UN quickly undertook to promote independence for these commoners or the people.

In 1960, the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonised Countries and Peoples affirmed that all commoners or the people have the right to determine their own government. With this declaration, the UN set itself the objective of putting an end to colonialism by affirming that foreign domination and exploitation were contrary to human rights. To better achieve this goal, the UN set up a Special Committee on Decolonization.

The UN also set up trusteeship regimes with the aim of fostering political, economic and social development and developing the capacity of commoners or the people to govern themselves, leading to true independence. The trusteeship regimes had to ensure that the governments in place achieved these goals, while respecting human rights. All the territories under trusteeship became independent or joined forces with neighbouring states.

The Declaration on Non-Self-Governing Territories served to guide the authorities of the Non-Self-Governing Territories. The administration was to be carried out with the interests of the inhabitants first and foremost, and with the obligation to promote their prosperity. To achieve this, political, economic and social skills had to be developed, and the necessary institutions and education put in place, while taking into account the aspirations of the inhabitants and the state of development of the territory. Countries administering other territories also had to communicate all their decisions to the UN.

The formation of new independent nations created the third world countries (underdeveloped and developing countries). As they emerged, these new countries immediately asserted their independence from the duality of the Cold War blocs.

After gaining political autonomy, many of the new nations were faced with ethnic and religious conflicts, the foundations of which had been laid during the colonial period. Some of these conflicts led to genocide. Democratisation is still difficult. A number of countries that gained their independence at this time are still grappling with problems of dictatorship and totalitarian governments.

Third world countries are then dependent on rich countries because they are still too indebted and dependent on agriculture to be able to develop a profitable and dynamic economy. Generally speaking, third world countries have a high birth rate, a low standard of living and a lot of poverty. This is why most former colonies have strong political links with the mother country. Moreover, the culture and language of the former mother country still influence these young countries.

India gained independence on 15 August 1947 after lengthy negotiations. Initially between the Indians and the British, these negotiations then took place between the Indians themselves. India had belonged to the British Empire since the 19th century. But from the beginning of the 20th century, Hindu elites were demanding independence. These intellectuals founded the Congress Party. On the other hand, inter-religious tensions arose and the Muslims created the Muslim League. They demanded the immediate departure of the British and the creation of a Muslim state: Pakistan. These Muslims refused to form a confederation with the Hindu party, as they were convinced that they would be subjugated by the Hindu majority.

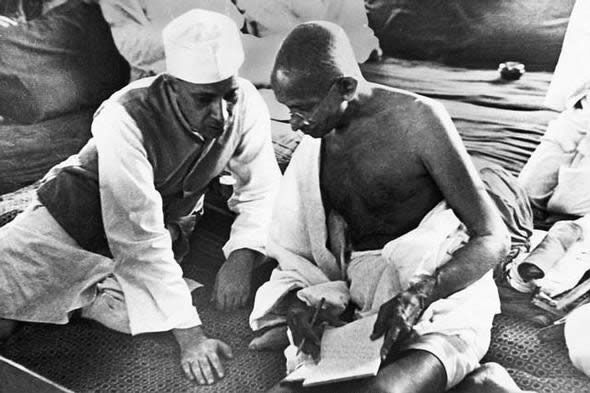

In 1909, the nation was divided into distinct communities. Hindu and Muslim representatives each had their own elected council. In 1919, the India Act established a constitution with provincial governments and local representative assemblies divided along religious lines. In 1920, the independence movement set out a programme of independence within the empire if possible. If necessary, independence should be achieved outside the empire. The leader of the independence movement was Gandhi, who advocated non-violence and the return of handicrafts to India.

In 1929, when Nehru was elected President of the Congress, he reached an agreement with the British. Unfortunately, the new constitution resulting from this agreement made India a federation of states and was rejected by the Muslim League, which demanded the creation of a purely Muslim state.

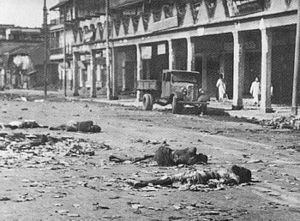

In 1942, at the height of the Second World War, the British offered independence in exchange for support in the war. Both the Congress and the Muslim League refused. The British retaliated by arresting all the Congress leaders. By 1945, everything was in place to achieve India's autonomy. A provisional government was set up in 1946, in which the Muslim League refused to participate. This League incited a day of direct action, Direct Action Day, during which massacres took place all over the territory. The largest massacre of Hindus took place in Calcutta, where 5,000 people were killed and 15,000 injured.

India was then on the brink of civil war. In 1947, given the state of emergency, India's autonomy was organised and proclaimed within five months. Gandhi and Nehru both had to accept the partition of their country to create Pakistan. The border between India and Pakistan was drawn by officials according to the majority religious group in the villages.

On 15 August 1947, independence was officially declared for India and Pakistan. The division of the territory triggered vast migrations: Hindus in Pakistan, fearing massacres, fled to India, and Muslims in India fled to Pakistan, fearing Hindu revenge. There were many clashes during this period of migration, resulting in 250,000 deaths. Today, India has succeeded in developing and ensuring its economic growth. Pakistan is still plagued by dictators and terrorist regimes.

On 18 April 1955, the Bandung Conference in Indonesia got underway. All the participating countries had been invited by the organising countries. Over 600 delegates represented African and Asian nations: Afghanistan, Cambodia, the People's Republic of China, Egypt, Ethiopia, the Gold Coast (present-day Ghana), Iran, Iraq, Japan, Jordan, Laos, Lebanon, Liberia, Libya, Nepal, the Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Syria, Thailand, Turkey, North Vietnam, South Vietnam and Yemen.

All these countries had a similar colonial past and were experiencing serious development problems. Together, these countries made up half the world's population, but accounted for only 8% of the world's wealth. The main issues discussed at the conference were the colonialist policies of France (as practised in North Africa) and the Soviet Union (as practised in Turkey and Iraq), and the problems in Taiwan, the Middle East and West New Guinea.

The conference took place from 18 to 24 April. In the final communiqué, the delegates set out their principles for a common policy based on a concern for equality and on the UN declarations. The most important statement concerned the autonomy of peoples. The text stipulated that peoples have the right to self-determination. In addition, the text condemned colonialist practices and racial segregation on the basis of the principles of equality of races and nations. The delegates also insisted on the need for economic and cultural cooperation between nations to promote better development.

In a different vein, the communiqué also proposed banning the manufacture and testing of nuclear weapons, imposing international control and finding ways of settling conflicts peacefully. It should be remembered that this conference took place at a time when the nuclear threat hung over the world. The greatest impact of the Bandung Conference was to stimulate the desire for independence throughout the world. The success of the other suggestions was much more symbolic than real, but they helped to define the ‘spirit of Bandung’ and contributed to the development of a new perspective: that of a more egalitarian world.

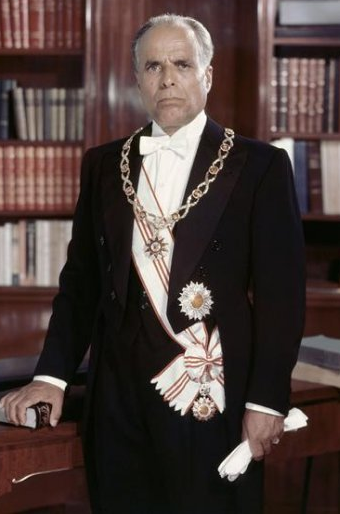

Born in 1903 in Tunisia, Habib Bourguiba was President of the Republic of Tunisia for thirty years, from 1957 to 1987. Trained as a lawyer, he campaigned for Tunisia's independence. He founded the Néo-Destour, a political party that aimed to liberate Tunisia from the French protectorate.

Tunisia gained independence in March 1956 and Bourguiba became the very first President of the Tunisian Republic.

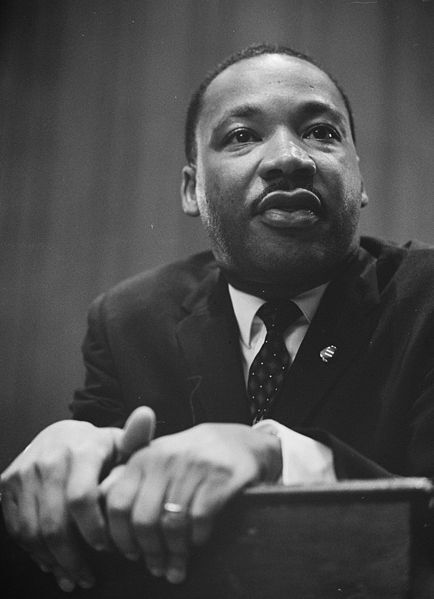

Born in 1929 in the United States, Martin Luther King was appointed pastor. He quickly devoted his life to the fight against racial segregation in his country. He was appointed spokesman for the Civil Rights Movement, inspired by Gandhi and his principles of non-violent struggle. This movement initiated pressure tactics such as boycotting racially segregated bus companies.

In 1959, Luther King visited India, where he was greatly inspired by Gandhi's ideas and pressure tactics. Many of the more violent black rights groups criticised his moderation. It was after a march in favour of civil rights that Luther King gave his most famous speech: ‘I have a dream’. Thanks to his political actions, laws to end segregation were established in 1964. That same year, Martin Luther King won the Nobel Peace Prize. Sadly, he was assassinated in 1968.

Born in 1931 in South Africa, Desmond Tutu was trained as a teacher. He began his studies at university, but resigned because of the poor education given to blacks, which he quickly objected to. He redirected his studies towards theology before going to London in 1966 to do his Master's degree, before returning to his native country. He had an impressive career in the Church: he was the first black South African to be appointed Dean of the Diocese of Johannesburg, Bishop of Lesotho and Archbishop. He was also appointed Secretary General of the South African Ecumenical Council. He used his position to mobilise the Church against Apartheid and in action for racial equality.

Desmond Tutu protested against both those who supported the Apartheid regime and those who wanted revenge. He won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1984 for his peaceful struggle. Since the end of Apartheid, he has never stopped denouncing what he considers to be unfair: the excessive salaries of members of parliament, the arms sales policy, his country's silence in the face of African dictators such as Roger Mugabe in Zimbabwe and Israel's attitude to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Nelson Mandela ‘s actions are strongly associated with Apartheid. A member of the African National Congress, Nelson Mandela resisted racial segregation in South Africa all his life. As a political prisoner, he was sentenced to life imprisonment. When he was released in 1990, he began negotiations with the President of South Africa to end apartheid. For his negotiating efforts and the beneficial effects of ending racial segregation, he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. Elected President of South Africa in 1994, Nelson Mandela devoted his energies to reconciling the peoples of his country.

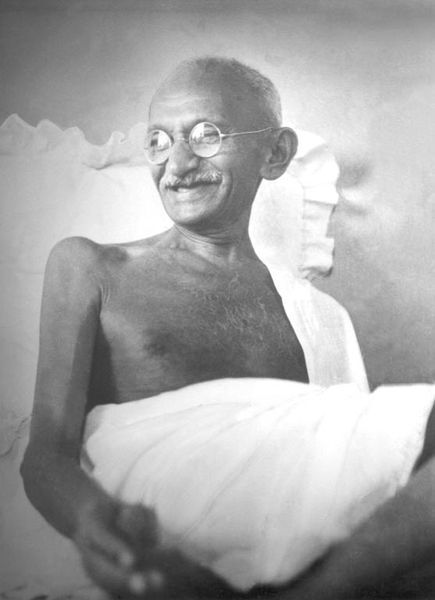

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi was born into a well-to-do family in India in 1869. Brought up with Hindu values, he was introduced to other religions at an early age and remained tolerant of them throughout his life. Married at 14, he did not hesitate to leave his wife and children to study law in London. As well as gaining an education in law, he also learned a great deal about all religions. When he returned to India in 1891, he was divided between Indian customs and Western values.

In 1894, he was sent to South Africa to defend the interests of an Indian company. There he discovered racial segregation and the domination of the British and Boers over the local population. He spent part of his time in South Africa fighting against injustices and laws, making people aware of the importance of social union. In 1906, faced with new segregationist laws, Gandhi began a movement of non-violent resistance. He was taken prisoner and it was during his stay in prison that he wrote Hind Swaras, in which he developed his theory of non-violent struggle.

In 1914, Gandhi returned to India, where he spent a year exploring his country. During his journey, he took part in several struggles against injustice, fasting to exert pressure and demonstrate his solidarity. He put into practice the principles of his non-violent struggle, satyagraha. At the end of the First World War, the first demands for Indian autonomy began. Gandhi caused a major demonstration in April 1919 during which he invited people to cease all activity.

Inspired by this demonstration led by Gandhi, the people staged a second demonstration a few days later. This time, things did not go so well, as the police did not hesitate to shoot at the peaceful crowd. More than 300 people were killed and 1,000 injured. Following this event, Gandhi put an end to his political actions. He resumed his means of action in 1920. At that time, his actions were supported by both the Congress and the Muslim League. He called for non-cooperation with the British and a boycott of textiles imported from Europe.

Clashes between the crowd and the police increased significantly. Until the day when 22 policemen were attacked by the crowd, after which Gandhi once again put an end to his actions. After being imprisoned for 2 years, the movement ran out of steam, but the population became divided. Gandhi called for social cohesion. To achieve this, he encouraged people to recognise the social equality of the Untouchables. He had to go on two hunger strikes before this demand was respected. In the 1930s, Gandhi became increasingly influential. He began a march to denounce the British salt monopoly. Gandhi marched for 24 days, covering 350 kilometres, during which time the crowds that accompanied him grew ever larger.

Indian society is divided into four castes, which can be compared to social classes. Belonging to a caste is determined by one's profession. However, certain occupations are excluded from these castes and are discriminated against (butchers, fishermen, midwives, etc.). These people are therefore called Untouchables and are excluded from the caste system.

At the end of his march, he announced the start of civil disobedience, before being arrested again. He was released following an exchange in which other political prisoners were freed and the salt laws were abolished. For his part, Gandhi ended his civil disobedience and took part in a conference in London. Unfortunately, it was also at this time that the divisions between the communities became more pronounced. In 1934, Gandhi retired from political life, but continued to fight for cohesion between the communities. He wanted independence for a united India.

In 1939, Gandhi refused to take part in the Second World War as part of the British army. In his view, only an independent India could be useful. After starting a new movement of civil disobedience, he was arrested again until 1944. After the violent events in Calcutta, Gandhi went on hunger strike to convince the Indians to drop their weapons, and Nehru stopped the massacres just in time to prevent Gandhi from starving to death. On the other hand, the frustrations of the extremist movements only increased. The extremist Hindus found Gandhi too conciliatory with the Muslims.

On 30 January 1948, Gandhi was assassinated by an extremist who wanted the creation of a Hindu state rather than a secular multi-faith state. This assassination followed four other attempts on his life. Gandhi is still an important figure today; he left a theory of pacifist struggle that would benefit from being used. During his political life, Gandhi was nicknamed Mahātmā, a word meaning great soul.

Born in 1906 in Senegal into a wealthy family, Léopold Sédar Senghor went to study literature in Paris. He was also a professor there. Throughout his life, he combined his various interests between teaching, literature and politics. He is renowned as both a politician and a poet. Along with other black writers, including Aimé Césaire, he defined the notion of negritude, which identifies black culture, its values and its identity. In 1945, he was elected as a member of parliament in Senegal and also published his first collection of poetry. He subsequently held various positions in Senegalese politics, before being elected president in 1960. He held this position until 1980, when he himself resigned. He was the first African leader to leave office of his own accord.

During his presidency, he invested in education and culture, encouraging the emergence of Senegalese thought, speech and cultural creation. He also invested in agriculture, fought corruption and created a tolerant and egalitarian democratic state. Although he did not win the Nobel Prize, many believe he richly deserved it. He was the first black man to be elected to the Académie française, in 1984. Senghor was a scathing critic of colonial regimes, but he was equally critical of the political organisations of independent countries, which were just as imperialist and armed as before decolonisation. He dreamt of a new civilisation born of the fusion of all races and cultures, in peace, equality and justice.