For several centuries, women were not legally recognized as the equals of men. Whether in terms of access to education, the professions or civil and legal rights, women were dependent on their husbands. Even the first declarations of human rights did not include women. It was only after many years of struggle on several fronts that women were able to achieve the level of legal equality they have today.

The battle for women's rights has included access to education, entry to the professions, the right to vote, the right to stand for election, the right to sit in government, the right to manage property, the right to divorce and access to fairer justice. But all this was not achieved at once and had to evolve over time. It should also be pointed out that the laws passed had the power to change the way society functioned legally. Women also had to take access to their rights and mentalities had to adapt to this new reality.

The first women's demands were made during the French Revolution. Some women took the opportunity of the social changes and equalitarian values of the time to demand certain changes. First of all, they wanted the right to primary education, access to health care and the right to work. They also wanted legal protection to support abandoned women and unmarried mothers, marriage reform and the right to divorce. In 1791, following the drafting of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, Marie-Olympe de Gouges in turn drafted the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and of the Citizen.

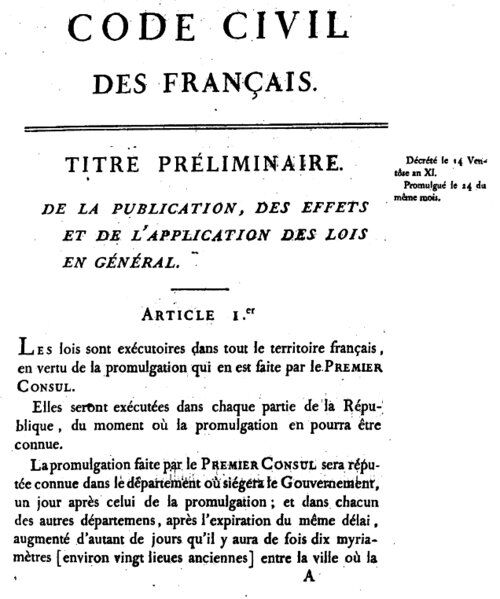

In her writings, she defended women's rights and the abolition of slavery. Marie-Olympe de Gouges was guillotined by Robespierre. In 1804, the entry into force of the Napoleonic Code put an end to these first attempts at women's rights.

The Napoleonic Code described the legal incapacity of married women: they were totally excluded from political rights. Women were therefore formally prohibited from attending high schools and universities. Married women also had no right to manage their property or sign contracts. In fact, they were not allowed to work or travel abroad without their husband's permission. The husband controlled his wife's entire life, including relationships and correspondence. Working women were not even allowed to collect their own wages. Women found guilty of adultery were severely punished by law. Unmarried mothers and their children had absolutely no rights.

The first women's rights convention was held on 19th July 1848 in the State of New York. During this meeting, women's demands were linked to the right to vote, political participation, access to work and the right to education.

In 1880, public secondary education was made available to women in France. In fact, access to education and instruction was women's first struggle. When schools opened their doors to them, it was said that their training would serve to make women better managers of the home as well as good educators for their sons. In reality, the women who studied saw it more as an opportunity to do something else and to take over the public space. Access to education gave women opportunities to fight for emancipation and advance their rights in all areas.

It was at the end of the 19th century, during the Industrial Revolution, that the first feminist movements appeared. Initially concerned with work, the debate also turned to the right to vote. Women first wanted to obtain conditions and salaries equivalent to those of men. Fighting for equal pay for equal work, women did not hesitate to set up trade unions and go on strike to get their way.

After gaining the right to education, women set about gaining civil and political rights. Focusing first on the right to vote, which they obtained at different times, depending on the country, women of the time also succeeded in obtaining certain work-related rights. For example, it was in 1907 that working wives could freely dispose of their wages. A little later, in 1909, maternity leave was introduced in France. After giving birth, women were entitled to eight weeks' rest, during which they could not be dismissed.

In 1920, women also gained the right to join a trade union without needing their husband's permission. Improvements to the education system continued at the same time. By 1920, women's and men's bachelor's degrees were deemed equivalent. The same applied to secondary school curricula, which by 1924, were identical for both men and women.

Legally, married women obtained a new status that allowed them to have an identity card, a passport and a bank account. However, husbands retained their rights of residence and paternal authority. In addition, husbands could still oppose the exercise of a profession.

Women's rights became more concrete after the war and the period of decolonization. In 1946, the United Nations set up a Commission on the Status of Women. This commission produced various texts, including the Convention on Political Rights, written in 1952, the Convention on the Nationality of Married Women in 1957 and the Declaration on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women, drafted in 1981.

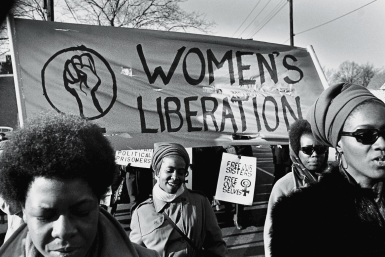

Launched by the revolutionary wave of 1968, the new feminism sought to promote women's equality while respecting their femininity. This equality had to be social, but it also had to be present in couples. Feminists wanted women to gain autonomy and independence in their relationships. In society, women demanded a place in political and decision-making circles.

The feminists of the 1960s and 1970s were primarily concerned with achieving equality between men and women. They also wanted official recognition of women's contribution to the well-being of society and the family. In concrete terms, feminists wanted to eliminate prejudices and practices that were harmful to women.

Moreover, it was in 1946 that men and women were deemed equal in the Constitution. In 1965, women gained the freedom to exercise the profession of their choice. In 1966, Betty Friedan founded the National Organisation of Women. The aim was to achieve total equality between men and women. This organisation also took a stand against the roles traditionally assigned to women.

A similar movement emerged in the United States in 1967. The Women's Liberation Movement fought for access to the professions and the right to abortion.

In 1970, what was described as paternal authority became parental authority. The mother's contribution was then officially recognized. Since 1995, the UN has acknowledged that women's rights are an integral and indivisible part of human rights.

Many feminists wanted to give women the right to control their own bodies: to have children if and when they wanted to. It was at this time that the battle for access to contraception and abortion predominated. In 1967, contraception was permitted in France. In 1971, a petition signed by 343 women, the Manifesto of the 343, who had had abortions, sparked a social debate. The petition called for the right to easy access to contraception and the right to legal abortion.

Among the signatories were Simone de Beauvoir, Jeanne Moreau and Catherine Deneuve. Abortion was legalized in France in 1975, while distribution of the contraceptive pill had been authorized since 1974. 1975 was also named International Women's Year, while the decade 1975-1985 was designated the United Nations Decade for Women. During this period, a number of feminist groups also fought against violence against women, rape and sexual assault. It was not until 1980 that rape was legally considered a crime in France.

In recent years, women have fought for parity and pay equity. Whether in politics or in the workplace, women want to be recognized. The aim of pay equity is to ensure that men and women are paid the same for equivalent work. Parity aims to increase the proportion of women in positions of power and decision-making (members of the Assembly, members of the Senate, company directors, etc.).

Some countries even require boards of directors to be made up of at least 40% women.

In France, half the candidates running for election must be women.

Despite the great advances made in the 20th century, there are still a number of challenges to be met: combating poverty and illiteracy, which affect more women than men throughout the world, and increasing the number of women in decision-making positions.

Strongly linked to civil rights, the right to vote was the battleground for women in the early 20th century.

At the time, women fighting for the right to vote were nicknamed suffragettes, after the word suffrage, which means a vote cast in an election.

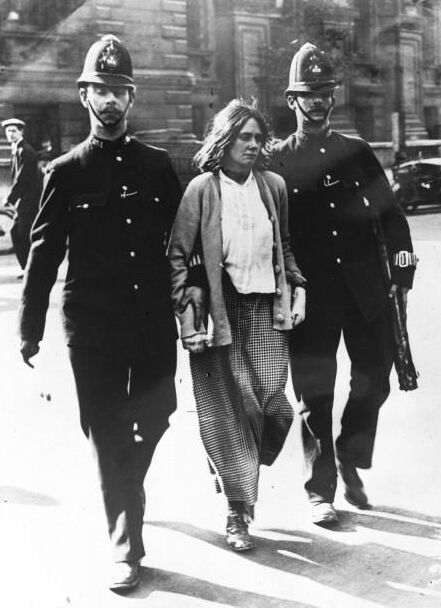

The first suffragette groups appeared in Great Britain in 1903. The suffragettes formed political and social unions whose main aim was to campaign for women's right to vote.

New Zealand was the first country where women had the right to vote, in 1893. The right was acquired after a petition was circulated. Although women had the right to vote, they did not have the right to stand as candidates until 1919. In all other countries, the right to vote for women was more difficult to achieve. In some countries, women had to resort to more violent means to make their cause heard.

Between 1908 and 1920, a number of suffragettes took part in protests in China, Switzerland, the United States, Canada, Paris and elsewhere. At the same time in London, 250,000 suffragettes were protesting in the streets. In Denmark, women who paid income tax were given the right to vote in 1908. The suffragettes in London took more violent means in 1913 when they caused explosions and destroyed telephone links. The suffragettes fought not only for the right to vote, but also for political equality and the right to stand for election to the communes.

At the time, Great Britain was exerting strong pressure on activists by convicting them or sending them to prison. Some suffragettes were injured as a result of police violence. Some countries soon gave women the right to vote. As early as 1914, women in Montana in the United States were granted civil rights, and in 1916 one of them was elected to her state's House of Representatives. Several countries followed this example: Denmark (1915), Great Britain (1918), the United States and Germany (1920) and France (1944).

In the United States, the new laws were to authorize women's rights and the rights of Black people. Civil equality was achieved through several treaties: the Civil Rights Acts. The first, signed in 1875, granted civil equality to blacks. Another treaty was signed in 1957. The most important was the Civil Rights Act of 1964. This officially put an end to racial segregation. All citizens had access to the same services and the same rights, regardless of colour, nationality, sex or race.

The entire US population gained the right to vote in 1965 with the Voting Right Act, which gave everyone the right to vote. Once the right to vote had been won, certain groups of suffragettes began to take up other causes such as ownership of the body, birth control, abortion and civic equality.

Because of its particular political structure (federal and provincial governments), Canada has moved at different speeds in the development of women's rights, with some provinces granting rights more quickly than others. In 1900, the federal right to vote was limited to those eligible to vote at the provincial level, which excluded all women and minorities. Over the course of the century, several new laws were created to promote equality between men and women.

The first provinces to give women the same legal capacity as men were Manitoba (1900), Prince Edward Island (1903) and Saskatchewan (1907). Despite these advances, some businesses, especially those owned by Asians, were unable to employ white women. In the years that followed, some provinces allowed women to vote in provincial elections: Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta (1916), British Columbia and Ontario (1917), Nova Scotia (1918).

In 1918, women who had the right to vote in their province could also vote in federal elections. By 1920, all Canadians aged 21 or over could vote. By 1929, women could even be appointed to the Senate. Women in Prince Edward Island gained the right to vote in provincial elections in 1922, while women in Quebec could not vote until 1940.

After the Second World War, governments began to introduce legislation to promote women's access to work and pay equity. Ontario (1951) and Saskatchewan (1952) were the first provinces to create legislation on these issues. In 1953, Canada, British Columbia, Manitoba and Nova Scotia followed with legislation on pay equity and fair employment practices. In the years that followed, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and Alberta created similar measures.

After tackling labour laws, governments adopted various human rights texts and codes: Ontario's Human Rights Code (1962), Nova Scotia's Human Rights Act (1963), Quebec's Charter of Rights and Freedoms (1975) and the Canadian Human Rights Act (1977). During these years, and thanks to these new laws, women acquired certain legal guarantees as well as the right to property.

Born into a bourgeois family, Marie Lacoste-Gérin-Lajoie quickly developed a passion for the law, in particular the various forms of legal discrimination against women. Self-taught, she became a legal expert and lectured at the Université de Montréal.

She wrote several legal treatises in which she attempted to Reformation the Civil Code. She fought hard to change the laws so that women would have the right to control their property and income and men would lose the freedom to spend all the family income. In 1907, Marie Lacoste-Gérin-Lajoie founded the Fédération nationale Saint-Jean-Baptiste. This foundation brought together a number of women from different professional backgrounds. Its aim was to promote women's civil and political rights. In 1922, she led a group of 400 women to demand the right to vote from the Premier of Quebec. The refusal meant that Quebec became the last Canadian province to grant women the right to vote, in 1940.

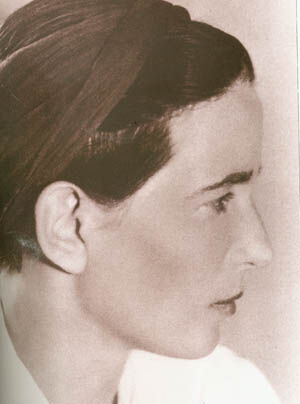

Born into a wealthy family and brought up by a Catholic mother, Simone de Beauvoir was attracted to study and writing from an early age. As an adolescent, she became an atheist and decided to devote her life to her studies. It was while studying philosophy in Paris that she met Jean-Paul Sartre, with whom she shared her life. After her studies, she taught and wrote extensively. Defending an existentialist philosophy (conceptualized by Sartre), she reflected on the meaning of life based on real life, concrete experiences.

Her work includes essays and fiction. Simone de Beauvoir's best-known and most-quoted work is The Second Sex, published in 1949. It quickly became the standard work of reference for the global feminist movement. In this essay, Simone de Beauvoir rejects the natural inferiority of women. According to her, “one is not born a woman, one becomes one”. She also defines the female gender, as described in various scientific and social theories. She then goes on to list the obstacles that stand in the way of women's lives. The solution, for this feminist philosopher, lies in work: “It is through work that women have largely overcome the distance that separated them from the male; it is work that can guarantee them concrete freedom”.

Marie Gérin-Lajoie is the daughter of Marie Lacoste-Gérin Lajoie. In 1911, Marie Gérin-Lajoie was the first woman in Quebec to receive a Bachelor of Arts degree. She later studied social sciences. Part of her studies were self-taught, because women were not allowed to continue their studies after the baccalauréat. That's why she went to New York in 1918 to study social services.

She later returned to Montreal where she worked in social action with women and families. Over the course of her life, she set up a number of structures to help women. In 1923, she created the Institut Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Conseil, through which she was able to set up a variety of organisations: social centres, playgrounds, shelters, and so on. In 1931, Marie Gérin-Lajoie also founded a school for social action. In 1939, when the School of Social Work opened at the Université de Montréal, Marie Gérin-Lajoie taught courses there. In 1940, along with Thérèse Casgrain, she took part in the fight for women's right to vote.

Thérèse Casgrain's activist career began when she replaced her ill husband, who was then a Member of Parliament. Thanks to this important position, Thérèse Casgrain, in association with a group, asked for the adoption of a bill to give women the right to vote. The response was negative and virulent. Everyone reacted: the provincial premier, the clergy and women.

At the time, married women in Quebec were considered minors. Not one to give up, Thérèse Casgrain founded the Ligue de la jeunesse féminine in 1926 and was president of the provincial suffragettes committee in 1928. This league became the Ligue du droit des femmes in 1929. Casgrain also made a name for herself with radio broadcasts on women's causes. When women won the right to vote in 1940, Thérèse Casgrain took up other causes, including child protection and prison reform.

In 1942, she stood for election. In 1945, she helped draw up the federal government's family allowance program. In 1955, she became the first woman president of a political party, the NDP (New Democratic Party). Thérèse Casgrain's other achievements included founding the Quebec section of the group Voix des Femmes (1961), taking part in a peaceful delegation to Moscow, being named Woman of the Century (1967) and a member of the Senate (1970). Before her death in 1981, Thérèse Casgrain received several prestigious awards and honours, as well as honorary doctorates. After her death, an award was named in her honour.

From the time she was a student, Simonne Monet-Chartrand was heavily involved in a number of causes before she met Michel Chartrand, who was involved in union causes and became her husband. In the 1950s, she helped set up a number of services: marriage preparation, a parents' school, an association of parent-teachers, a family union, cooperatives and the Centrale d'enseignants du Québec.

In the 1960s, she founded the Fédération des femmes du Québec, participated in Voix des femmes, in the nuclear disarmament movement and created the Institut Simone de Beauvoir. Throughout her life, she led a number of organizations and institutions that served the cause of feminism, education, society and nationalism.