In the early 1960s, women made up one third of the workforce. Many women worked traditional ‘women’s jobs’ such as secretaries, librarians, teachers, waitresses and nurses, and they were usually paid less than men for doing the same work.

Although women won the right to vote in 1940, they were not very involved in politics before the Quiet Revolution since the Catholic Church believed that they should avoid making decisions and, instead, do what their husbands told them. During his years in office, Maurice Duplessis had close ties to the Church, and therefore supported this view and only proposed male candidates to represent his party in elections.

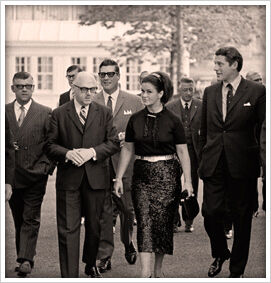

In the midst of the social changes brought about by the Quiet Revolution, Marie-Claire Kirkland-Casgrain was elected as the first female member of Quebec’s National Assembly in 1961. In 1964, she was appointed Minister of Transport and Communications, becoming the first woman elected Cabinet minister in Quebec. The same year, Bill 16 was passed, putting an end to the previous “legal incapacity of married women” promoted under the Duplessis government. According to Duplessis’s position, a married woman could not sign a contract, own property or execute a will without her husband’s consent and signature. With Bill 16, married women enjoyed these new rights.

In Quebec, the Fédération des Femmes du Québec was founded in 1965 and chaired by Thérèse Casgrain. Members demanded a commission of inquiry on the status of women. The Royal Commission on the Status of Women, which began in 1967, led to the tabling of the Bird Report, which provided a wealth of information on this issue.

The Bird Report recommended ways to improve women’s status: establish equal pay, create a network of childcare centres, offer maternity leave, allow women access to management positions, etc. More women were slowly gaining access to higher education, giving them access to less traditional jobs.

Before 1964, women’s education was severely limited, rarely going beyond basic French and mathematics. Besides these two subjects, young girls were mainly taught religion and home economics, such as cooking, sewing and housekeeping. They very rarely had access to higher education in colleges and universities. This meant that women were often forced to choose traditionally female jobs’ such as secretaries, nurses and teachers.

In 1964, education reforms granted women more access to higher education. Although more women accessed less traditionally female jobs after graduation, many then left these jobs after getting married due to social pressure. At the time, people believed it was the man’s role to provide financially for his family, while women took care of the home and the children, which stopped them from having jobs outside the home. Because of this perception, society frowned upon married women and mothers who worked. Despite new higher education and employment opportunities, many women looked after their families.

Even though abortion was still illegal in the 1960s, various forms of contraception became more available, granting women more control over their own bodies. The birth control pill became available in Canada in 1961, allowing women to control their pregnancies. However, it was illegal to use the pill as a contraceptive, and it was only intended to regulate menstrual cycles.

Even so, by 1965, more than 719 500 women in Canada were on the birth control pill. The Clergy had banned the pill in Quebec and yet, the birth rate was declining. Abortion remained illegal until 1969, when Pierre Elliott Trudeau made it legal under certain conditions, further leading to a decline in the birth rate.