The concepts covered in this sheet go beyond those seen in secondary school. It is intended as a supplement for those who are curious to find out more.

Industrialization in France was slower than in England. France still benefited from the same technical innovations, but the pace of agricultural and industrial mechanisation was slower. What's more, the Industrial Revolution had much the same impact as in England: urbanization, poor living conditions for workers, new social classes and so on.

The agricultural revolution in France has not been as meteoric as elsewhere. There were several reasons for the slow mechanisation of agriculture. Unlike in England, French farmland was subdivided into small parcels. There were no large estates. There was little interest in developing agriculture.

Since the French Revolution, the proportion of small and medium-sized farmland has increased. The infrastructure needed for mechanisation was lacking: there were no means of transport, restrictions on the movement of agricultural products and severely regulated structures. Farming could not specialise, and each farmer produced a variety of products that almost exclusively supplied the local market. What's more, peasants were not wealthy enough to invest in new tools.

This situation partly explains why, at the beginning of the 19th century, the country was essentially agricultural. In 1846, when the Industrial Revolution was already well underway in England, France's rural population still accounted for 75% of the country's total population.

In the second half of the 19th century, the situation changed somewhat: French farmers adopted fallow land and land rotation, increased the amount of land available for cultivation and improved their machinery. They also introduced new crops from America: potatoes and maize. All these changes increased the productivity of the land. However, the agriculture practised was still subsistence farming. The slow growth of agriculture is justified by the social upheavals experienced by the country: the French Revolution and Napoleon's Empire.

Subsistence farming produces just enough food to feed the farmer and his family. This type of farming produces very little surplus.

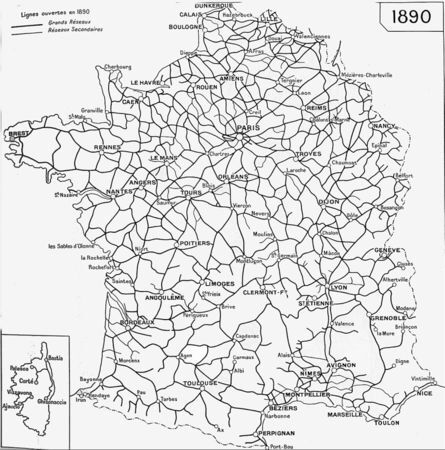

It was the arrival of the railway that transformed the lives of peasants. The countryside became more accessible, fertilisers and foodstuffs were transported by train, and the market expanded. Faced with this new situation, peasants gradually specialised and production increased.

Although farming practices have changed, France has not been quick to set aside its long tradition of agriculture.

It was the textile and metalworking sectors that were first affected by industrialization in France. By the middle of the 18th century, the textile sector was in the throes of proto-industrialization, with artisans working in a number of workshops and factories. Proto-industrialization was accentuated by the importation of English techniques and the arrival of several British families. France already possessed the same technical resources as England, but developed less rapidly.

The delay in the development of the metallurgical industry goes some way to explaining why French industrialization did not spread rapidly. In fact, from the 18th century onwards, metallurgy in France was lagging far behind, which slowed down the development of the textile sector and also that of the military. In 1764, a number of entrepreneurs studied English methods before setting up the first factories. It wasn't until 1777 that the first blast furnaces were installed and in 1784 that the first rotary steam machine was set up. Despite these imports, France lagged behind: coal supplies were insufficient. Indeed, France did not have as good coal reserves as other countries.

Yet France played an important role in the Industrial Revolution, despite the slow pace of development. Several major engineering schools were founded between 1747 and 1828. These schools inspired many other countries and French engineers were in demand everywhere.

At the beginning of the 19th century, only the textile industry was largely mechanised.

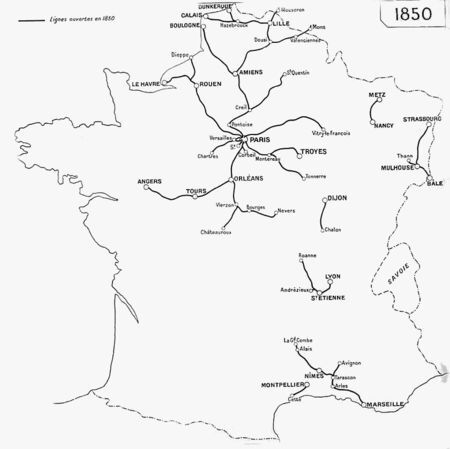

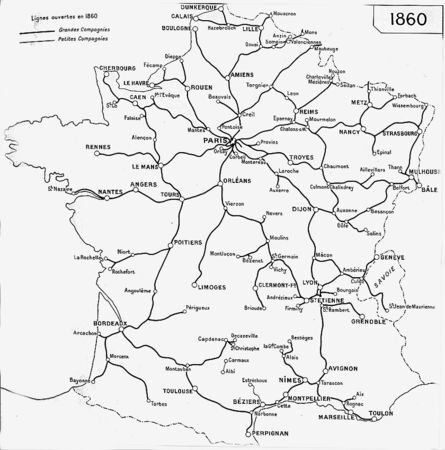

It was in 1850, with the arrival of the railway, that the situation changed: the iron and steel industries underwent major developments. Railway networks needed steel (used from 1866 to make rails), coal, iron and steam machines.

From that time onwards, the rural population began to decline in favour of the cities.

Thanks to the development of the railways, France was able to develop its economy, despite lagging behind England, Germany and the United States. The French bourgeoisie preferred abstract tasks, legal functions and land ownership to industrial property. The railways were also in their interests. As a result, the network developed rapidly, centred on Paris.

The establishment of the railways by the owners of the networks and the owners of the industries encouraged the development of two new social classes: the business bourgeoisie and the proletariat. The misery of the workers led to numerous social movements in which the workers made their demands known. At the same time, major cities were being redeveloped, with improved sewers and boulevards. In Paris, Haussmann was the leader. In 1914, France was one of the richest countries in the world. Paris had a very good reputation, especially since the Universal Exhibition of 1900.

As elsewhere, industrialization in France gave rise to social debates. Workers' living and working conditions were miserable: low and inadequate wages, hard labour for children, insalubrious housing and towns, etc. Industrialization was marked by class struggle and labour rights. Industrialization was marked by class struggle and labour rights. Since the French Revolution, individual freedom had taken precedence. The freedom of industrialists undermined the rights of workers, who had no protection from their bosses.

The first labour law was introduced in France in 1841. This law prohibited work for children under the age of 8, limited the working day for children aged between 8 and 12 to 8 hours, and also limited the working day for children aged between 12 and 16 to 12 hours. In addition, children under the age of 13 were not allowed to work at night. However, this law was not really enforced, as there were virtually no inspections in the factories. What's more, parents wanted their children to work because the family didn't have enough money.

In 1845 and 1846, poor harvests led to food shortages. Food imports rose, as did food prices and the cost of living. Farmers and workers were even poorer than they already were. The poorer people were buying fewer industrialized goods. Industrialists found themselves producing more, at the same time as exports were falling. Not being able to produce as much, the bosses fired a number of workers who found themselves out of work, while everything cost more. This was the beginning of the industrial crisis.

In January 1847, a number of banks were in financial difficulties, and some went bankrupt, including the Caisse du Commerce et de l'Industrie. Interest rates rose sharply. Despite a bumper harvest in the summer of 1847, the price of wheat plummeted, driving peasants and speculators to ruin. At the same time, railway investors reaped less profit than they had hoped and pulled out. Railway construction came to a halt, putting 800,000 workers out of work. All industries had just lost their main customer.

In 1850, the government intervened by introducing an agricultural policy. The main aim of this policy was to prevent a crisis like this from happening again. In 1852, the economy recovered thanks to the discovery of precious metals. Industrial production resumed and the financial situation returned to normal.

In 1871, France lost a war against the Prussians. This defeat left Parisians feeling humiliated and even betrayed by their government. Fearing revolutionary movements, the head of the Republic and the government moved to Versailles.

From Versailles, the government imposed a number of measures that reduced the quality of life of citizens: compulsory repayment of businesses and rents, withdrawal of the allowance paid to the national guard. At the time, the national guard comprised more than 180,000 men, all of whom were left without a source of income. Tension was rising rapidly in the French capital.

At the same time, the government, still in Versailles, wanted to recover 227 cannons. These cannons had been installed in Montmartre during the war against the Prussians. On March 18, 1871, 4,000 soldiers set off for Paris with orders to bring back the 227 cannons. The Parisian population would not let them: there was a riot during which two generals were taken prisoner.

A few hours later, these two prisoners were executed as riots broke out all over the city. The members of the national guard formed a federation and called themselves the fédérés. Following these unforeseen events, the government ordered the soldiers, whose loyalty was uncertain, to evacuate Paris that evening.

Militants, anarchists, socialists and Jacobins then took control of the city. Thirty of them met in the confusion at the town hall, before forming a new central committee. On March 26, this committee called municipal elections. On March 28, the Paris Commune was declared: 79 elected representatives controlled the city, independently of the government.

These newly elected representatives drew up a Declaration to the French people, in which they proposed to the other cities of France that they create a federal association. The Paris Commune attempted to govern the capital, while putting down revolts and assaults by soldiers.

The French army succeeded in putting an end to the Paris Commune after Bloody Week, which began on May 21, 1871. The government, having assembled a sufficient army, launched an assault on Paris. The aim was clear: to put an end to the Commune and regain control of the capital.

To achieve this, the army had to conquer Paris barricade by barricade. At the same time, the Commune voted in favour of the Hostage Decree, which allowed hostages to be executed without trial. Throughout the week of fighting, the Federals executed around 40 hostages and set fire to the city. In all, 4,000 people lost their lives in the fighting.

On May 28, 1871, the army regained control. This marked the end of the Paris Commune. Some 38,000 people were arrested.

In 1889, May 1st became an official day of demands for workers. On this day, workers generally went on strike and took advantage of the opportunity to demonstrate, put forward their point of view and their value, make their demands known and so on. Today, May 1st is still celebrated in many countries as the International Workers' Demands Day.

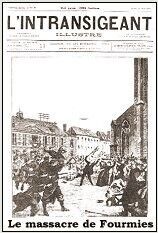

On April 29, 1891, the bosses of the town of Fourmies were apprehensive about May Day, with its strikes, demonstrations and demands. That's why the bosses drew up a text: Le Manifeste des Industriels contre le 1er mai, in which they tried to convince their workers not to take part in May Day activities. According to the bosses, workers' movements could only lead to the ruin of industry.

In addition, the industrialists of Fourmies considered that their workers' working conditions were above average. What's more, the industrialists, through this manifesto, had undertaken to defend themselves in this unjustified struggle. When the industrialists saw that the workers still wanted to take part in strike activities, they feared the possibility of riots. It was to counter possible riots on May 1st that the bosses demanded that soldiers be sent to Fourmies.

On the morning of May 1st, 1891, as expected, the workers did not work, except for a few. The striking workers wanted to stop the activities of those who were working. Sensing rising tension, troops of soldiers charged the strikers before arresting two of them. The unrest didn't stop there in Fourmies: in the afternoon, large numbers of demonstrators gathered to demand the release of the two prisoners. The soldiers again charged at the demonstrators, who threw stones at them. At 6.30pm, the soldiers were ordered to open fire on the crowd. The shooting lasted only a few minutes, but left 9 people dead and 35 injured.

Since then, this event has been engraved in the memories of all Socialist activists.

The arts of 19th century France were marked by social transformations. Many writers and artists wanted to depict the harsh reality of workers and city dwellers. Works of art no longer aimed simply to embellish reality, but to represent it as faithfully as possible. A number of 19th century novels and paintings depict popular characters: workers, miners, train passengers, peasants, small shopkeepers and so on.

In his collection of poems, Victor Hugo brought together a number of poems, some of which recount moments in his life. Published in 1856, Les Contemplations brings together texts written between 1846 and 1855.

When Victor Hugo wrote these poems, he was in exile in England. It should be pointed out that Victor Hugo did not just write poems, novels, plays and protest texts. He was heavily involved in political life before becoming actively involved in revolutionary movements, which is why he had to go into exile.

In fact, most of Victor Hugo's texts are aimed at making his readers aware of certain social problems, as in Les Misérables and Le dernier jour d'un condamné (The Last Day of a Condemned Man). Divided into 6 books, Les Contemplations divides the poems according to certain themes: the author's youth, his love affairs, the death of his daughter, meditation and hope. The third book, however, focuses on pity. It is in this book that Victor Hugo sensitively depicts the misery of cities and modern society.

During the Paris Commune, the Fédérés felt the pressure exerted by the Versailles government. The poet Eugène Pottier wrote a poem designed to give the insurgents a boost. A few years later, in 1888, Pierre Degeyter set the poem to music. A true revolutionary song, it officially became the anthem of the world workers' movement in 1904. Since then, The Internationale has been translated into many languages. Many communist parties have also chosen it as their official song.

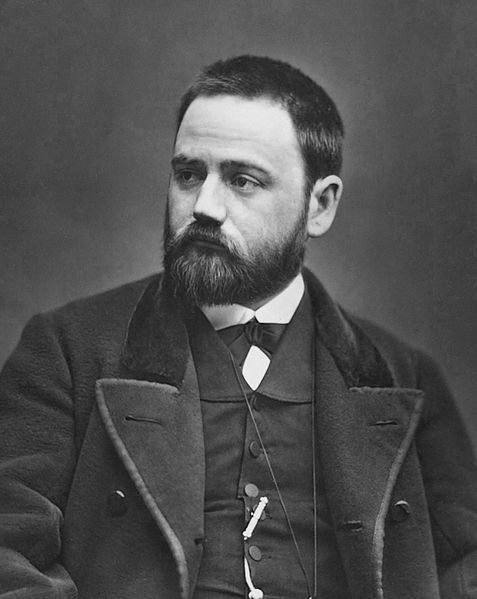

Germinal was published in 1885. Zola's text was part of his vast writing project. Émile Zola wanted to create a new genre of novel, more suited to society: the naturalist novel. Zola's aim was above all to interpret and understand natural phenomena through writing.

In fact, Zola was inspired above all by the scientific method of experimentation, in order to ascertain how and by what means the characters are conditioned: social environment, work, family, and so on. In this way, he sought out the hereditary causes of vice. To achieve this, it was essential for the writer to maintain an objective, realistic view of his subject. Most of Zola's characters come from the commoners or the urban society.

Germinal, like all the Rougon-Macquart novels, is an example of class struggle and social revolt. Zola's point of view, although objective, attempts to show the misery in which the workers live. In Germinal, Zola portrays a young unemployed man, Étienne Lantier. The story takes place in the midst of an industrial crisis: jobs are scarce and living conditions miserable.

The protagonist nevertheless manages to find a job in a mine. Zola's narration gives a powerful and strikingly realistic picture of the world of the worker. From an early age, the young hero was revolted by the social injustice and living conditions of the miners. He quickly spread his revolutionary ideas among his fellow miners, while the company cut workers' wages. Étienne Lantier encouraged the miners to go on strike. The bosses were intractable and the workers were increasingly hungry.