Digestive processes are all the steps that food undergoes as it passes through the digestive tract.

Digestive processes allow food to enter the body, move through the digestive tract and transform nutrients into simple molecules that can be absorbed by the body. They also enable the removal of non-digestible food residue.

The main digestive processes are listed here.

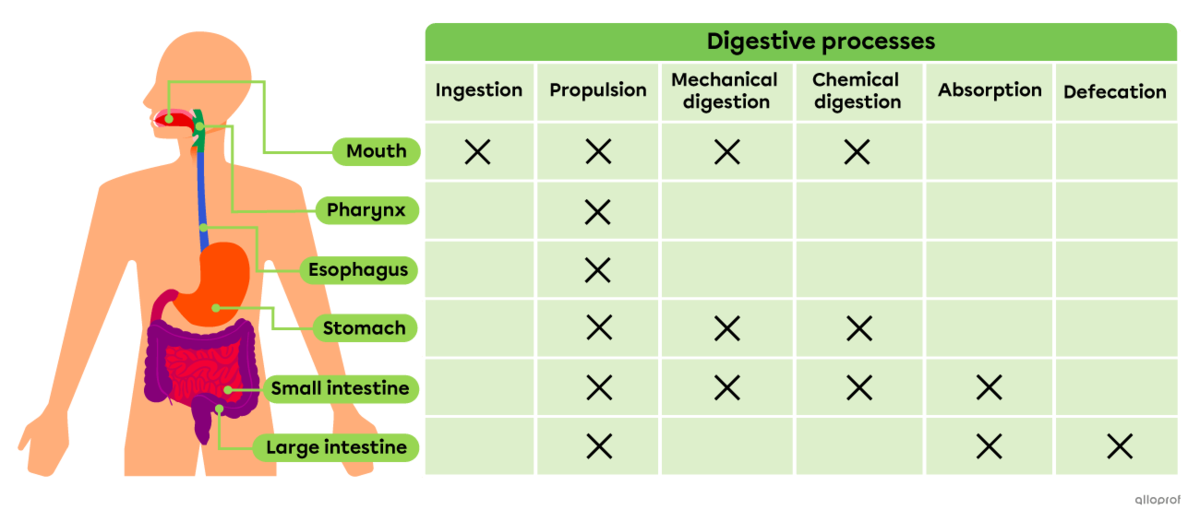

The organs of the digestive tract are where one or more digestive processes take place. The following picture and table match the organs of the digestive tract with the digestive processes that take place in them.

Ingested food undergoes several transformations as it moves through the digestive tract. As a result, the physical and chemical properties of the mixture contained in the digestive tract vary considerably from one organ to another.

Depending on the organ in which it is found, the contents of the digestive tract are identified by different terms. The following table provides the names given to the contents of the digestive tract according to their composition and the organs in which they are found.

|

Mixture name |

Mixture composition |

Digestive tract organ(s) |

|---|---|---|

|

Food bolus (alimentary bolus) |

food + saliva |

mouth, pharynx, esophagus |

|

Chyme |

food bolus + gastric juice |

stomach |

|

Chyle |

chyme + bile + pancreatic juice + intestinal juice |

small intestine |

|

Fecal material (feces) |

unabsorbed food residue + mucus |

large intestine |

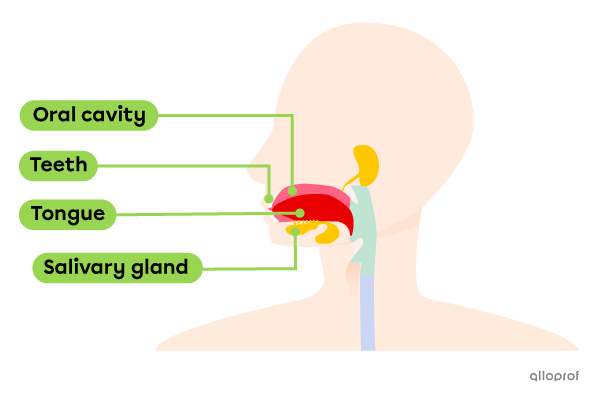

Ingestion is the introduction of food into the digestive tract. Food is ingested through the mouth.

Propulsion is the process of moving food along the digestive tract.

The propulsion of food is carried out by two mechanisms: deglutition and peristalsis. Food is propulsed in one direction only: from the mouth to the large intestine.

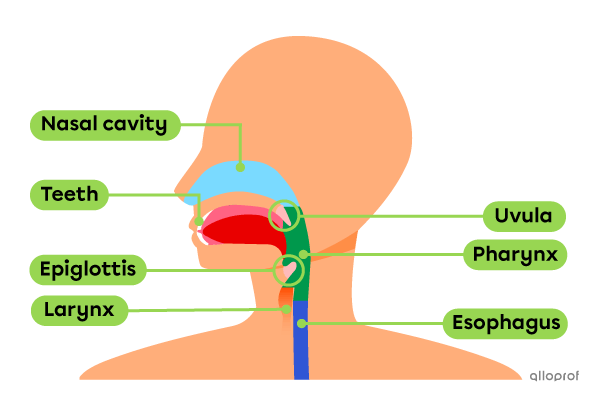

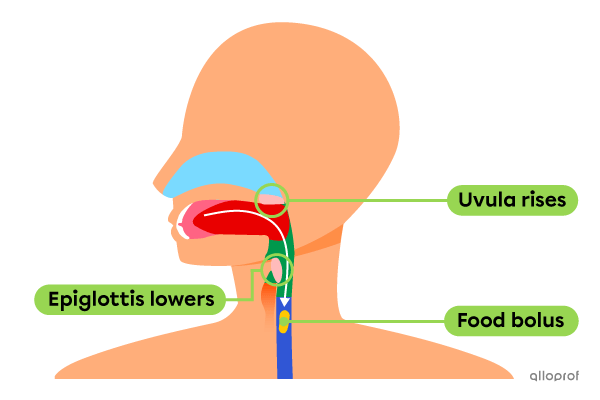

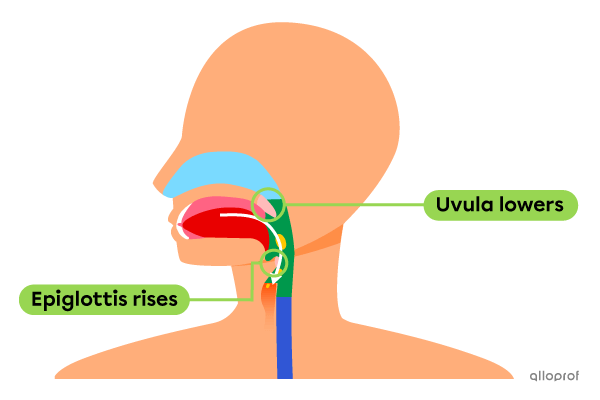

Deglutition is initiated when the food bolus is voluntarily pushed against the palate by the tongue, sending the food to the pharynx. The presence of food in the pharynx triggers a series of involuntary contractions that force the food into the esophagus. During this process the nasal cavity is blocked by the uvula and the larynx by the epiglottis.

When food is swallowed, it passes from the oral cavity to the pharynx and then to the esophagus. To ensure that the food enters the esophagus and continues its path in the digestive and not in the respiratory system, the larynx is blocked by the epiglottis and the nasal cavity is blocked by the uvula.

If air is inhaled when food is passing into the pharynx, the opening of the larynx may not be completely covered by the epiglottis. Therefore, the food may take the wrong path and go down the trachea. This is when food is said to go down the wrong pipe.

The presence of food in the trachea triggers a coughing reflex, which usually clears the airway.

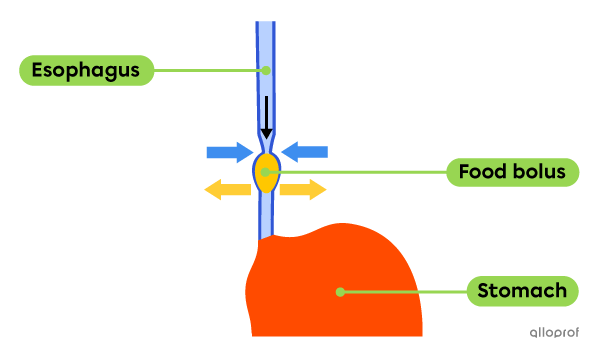

Peristalsis is a series of involuntary contractions and relaxations of the muscles that make up the walls of the digestive tract. These movements allow the propulsion of food in a single direction under normal circumstances.

Peristalsis ensures the progression of food through the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. In addition, peristalsis contributes to the mechanical digestion by mixing the food to a certain extent.

After deglutition, the food bolus is gradually pushed to the stomach by the peristalsis of the esophagus walls.

Mechanical digestion involves breaking up the food into smaller pieces and mixing it with digestive secretions.

Mechanical digestion of food is a process that facilitates chemical digestion. Reducing the size of the food pieces increases the surface area of contact between the nutrients and the digestive enzymes, which helps break them down into simpler molecules.

Here are four processes of mechanical digestion.

Mastication, also known as chewing, is a movement of the jaws that allows the teeth to grind food.

During chewing, the cheeks and closed lips hold the food between the teeth while the tongue mixes saliva with the chewed food.

Once well mixed with saliva, the food is compacted by the tongue and forms a mass known as the food bolus or alimentary bolus.

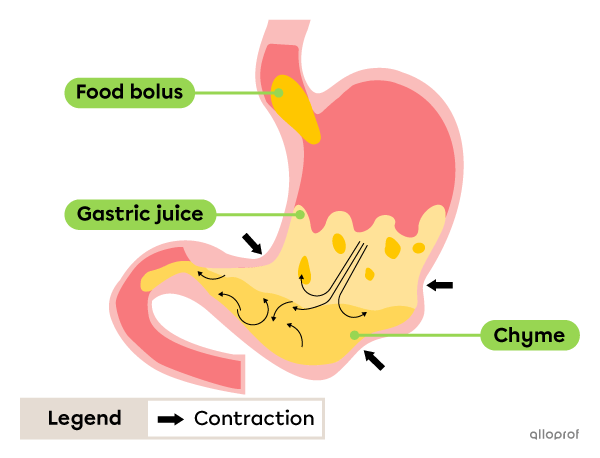

Churning is the rhythmic contractions of the walls of the stomach, which squeeze its contents and mixes in the gastric juice. Once thoroughly churned and mixed with the gastric juice, the contents form a slurry called chyme.

Segmentation is the repetitive and stationary contraction of the walls of the small intestine. These contractions fragment the contents of the small intestine, while mixing them with the various digestive secretions. Once well segmented and mixed, the contents of the small intestine become a whitish liquid called chyle.

In contrast to peristalsis, segmentation does not cause a significant progression of food through the digestive tract.

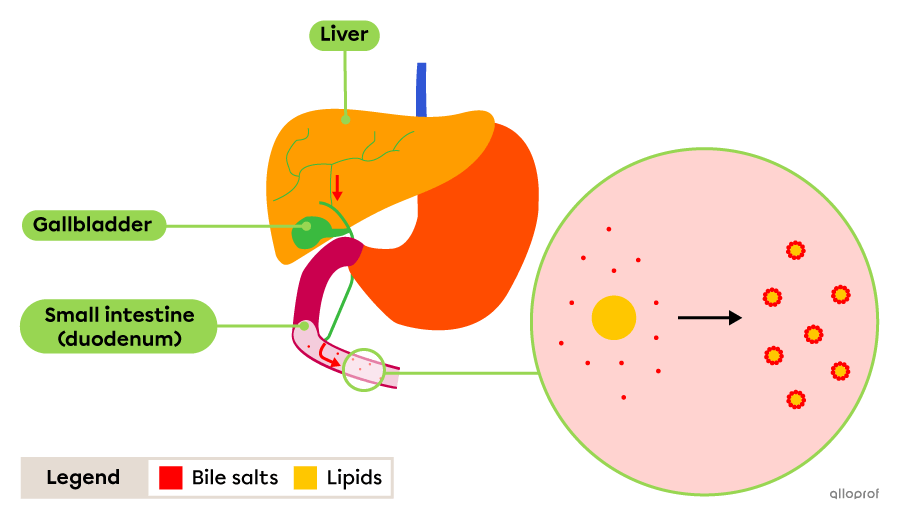

Since lipids are fats, they are not soluble in chyle, which mainly consists of water. The insolubility of lipids in water hinders their breakdown into simpler molecules that can be absorbed by the body.

This is why the emulsification of fats is essential.

The emulsification of fats is the transformation of fat clusters into much smaller droplets and their distribution throughout the contents of the small intestine.

The emulsification of fats is performed in the small intestine by the bile produced by the liver. More specifically, the bile salts contained in the bile surround the fats in a soap-like manner and enclose them in numerous tiny water-soluble capsules. The fat cluster is transformed into fine lipid droplets that are distributed in the chyle.

Once the fat has been emulsified, it becomes easier to break down the lipids into simpler molecules that can be absorbed by the body.

Fat emulsification is not a chemical digestion process. Unlike digestive juices, bile does not contain digestive enzymes capable of breaking down lipids into simpler molecules that can be absorbed by the body. The bile salts in bile only reduce the size of the lipid clusters and mix them with the digestive juices, which is a mechanical digestion process.

-

Chemical digestion involves breaking down the chemical bonds of complex molecules, in order to convert nutrients into simpler molecules that can be absorbed by the body.

-

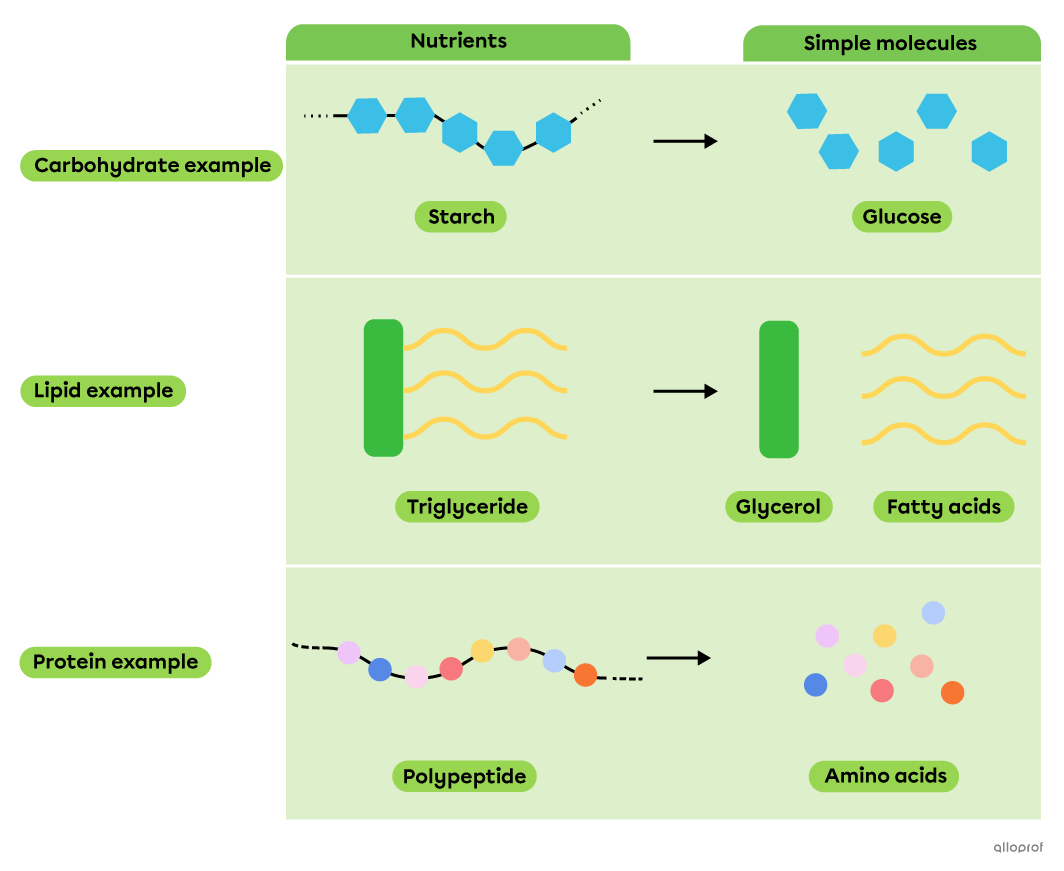

Nutrients are complex molecules found in food that break down into small enough molecules to pass through the walls of the digestive tract and be dissolved in the blood or lymph.

During chemical digestion, nutrient molecules are broken down into simpler molecules that can be absorbed by the body. For example, a carbohydrate can be transformed into a simple sugar (glucose, fructose, etc.); a lipid can be transformed into glycerol and fatty acids; and a protein can be transformed into amino acids.

The image below shows the main nutrients that make up food, as well as the simple molecules made accessible through chemical digestion.

Chemical digestion is performed by digestive enzymes found in the digestive juices.

-

Digestive juices are secretions from digestive glands containing digestive enzymes.

-

Digestive enzymes are proteins capable of accelerating the breakdown of certain complex molecules.

As food moves through the digestive tract, digestive juices are produced by certain digestive glands and added to the contents of the digestive tract.

The following table shows the digestive juices, the digestive glands that secrete them, where they are released and their main roles in the chemical digestion of food.

| Digestive juice | Digestive glands | Location of release | Role(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

Small intestine |

|

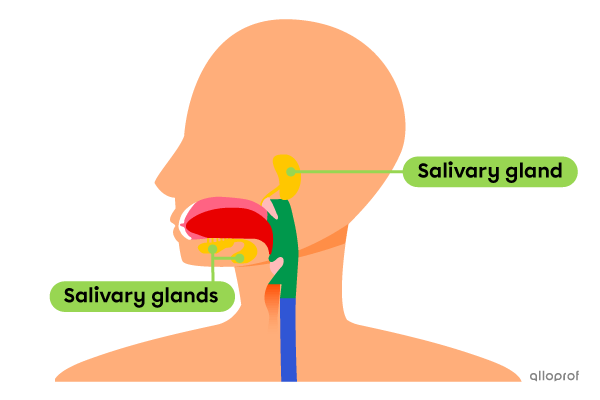

Saliva is secreted by the salivary glands in the mouth. It contains, among other things, an enzyme called salivary amylase.

Salivary amylase is a digestive enzyme that initiates the breakdown of certain carbohydrates, such as starch and glycogen.

Saliva plays an important protective role in the oral cavity. Among other things, it contains enzymes that prevent bacterial growth in the mouth and proteins that generate an immune response to pathogens.

Saliva also allows us to taste food. The flavour substances in food must be dissolved in saliva in order to be perceived by the taste receptors, which are mainly located in the taste buds of the tongue.

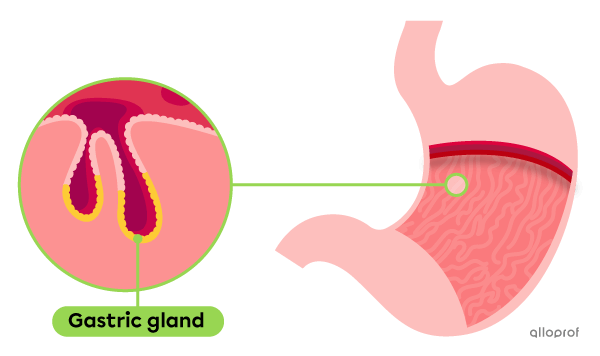

Gastric juice, often referred to as stomach acid, is secreted by the gastric glands, located in the inner lining of the stomach.

Gastric juice contains pepsin and hydrochloric acid (HCl), among other things.

Pepsin is a digestive enzyme that initiates the breakdown of proteins into amino acids.

Hydrochloric acid (HCl) optimizes the effect of pepsin.

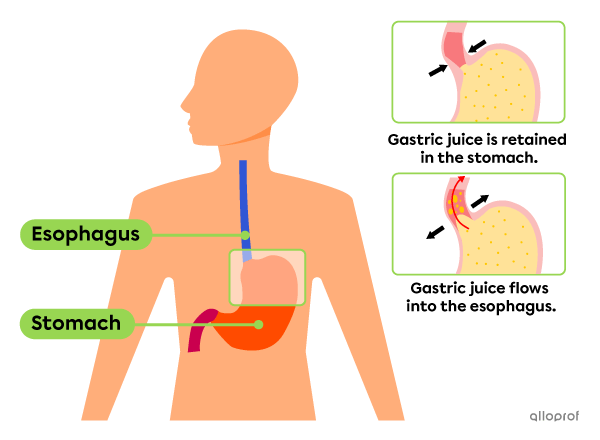

Heartburn is a burning sensation accompanied by pain at the sternum level. This sensation is caused by gastroesophageal reflux, which is when the gastric juice from the stomach rises into the esophagus.

Gastroesophageal reflux, commonly called acid reflux, is caused by the weakening or loosening of the lower esophageal sphincter. When this muscle relaxes, it allows gastric juice to flow up into the esophagus.

Heartburn can occur after consuming too much. It can also occur during pregnancy or in obese individuals when the abdominal organs are compressed upwards.

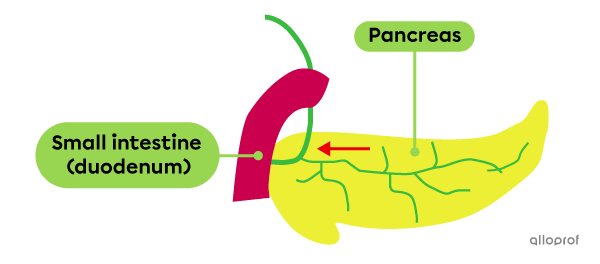

Pancreatic juice is secreted by the pancreas and released into the upper part of the small intestine, the duodenum.

Pancreatic juice contains various digestive enzymes that enable the breakdown of all types of nutrients.

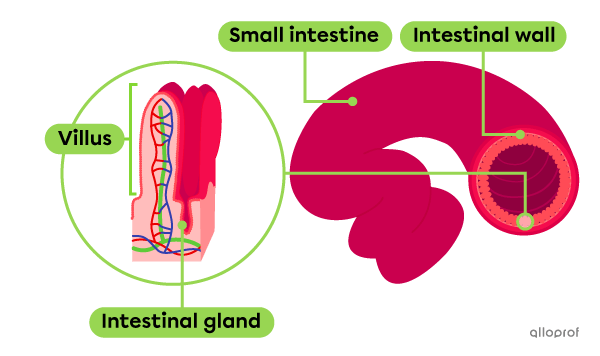

Intestinal juice is secreted by intestinal glands located at the base of the villi lining the inner wall of the small intestine.

The intestinal juice contains a small amount of digestive enzymes to complete the chemical digestion of proteins and carbohydrates.

Absorption is the process of nutrients broken down into simple molecules passing from the digestive tract into the bloodstream or lymph.

Water, vitamins and minerals are nutrients that are small enough to be absorbed without undergoing processing. Other simple molecules such as amino acids, glucose, glycerol and fatty acids are made available through mechanical digestion of ingested food and chemical digestion of nutrients.

Most absorption happens in the small intestine. Folds, called villi, line the inner wall of the small intestine. The surface of the cells lining the villi is also covered with microscopic projections, called microvilli. This configuration favours the absorption by greatly increasing the contact surface between the contents of the small intestine and its wall. Nutrients and simple molecules then pass through the wall into capillaries and lymphatic vessels.

When the contents of the small intestine flow into the large intestine, the absorption of nutrients and simple molecules is largely complete. While 90% of water is absorbed by the small intestine, the large intestine absorbs some of the remaining water from undigested food. The large intestine also allows the absorption of vitamins, some of which are synthesized by the thousands of bacteria it contains. These bacteria form the bacterial flora of the large intestine.

-

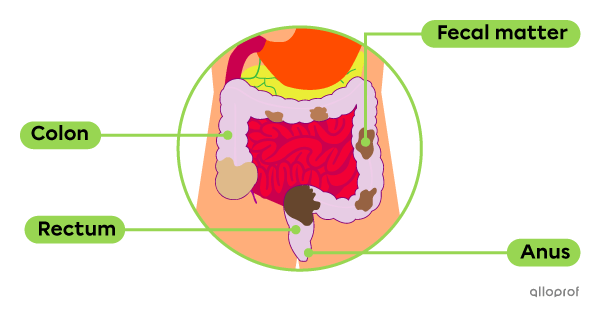

Defecation is the elimination of fecal matter from the body.

-

Fecal matter, or feces, is a mixture of water, mucus, indigestible food residues and bacteria resulting from digestion.

Once in the large intestine, the food residue moves by peristalsis into the colon, where the last of absorption is completed and fecal matter is formed. Fecal matter then enters the rectum, which is the last segment of the large intestine, where it is stored until elimination. The accumulation of feces causes the wall of the rectum to stretch, triggering a defecation reflex.